Page 24 - World Journal of Laparoscopic Surgery

P. 24

Nava Navaneethan, Peter Hewett

Statistical Analysis The interaction effect of surgical level and warm-

up was not included in the model because it was not a

Performance on the laparoscopic trainer is recorded and

analyzed by a software (InSTrAC) and quantitative significant predictor of time. A significant interaction

measures are obtained. effect would suggest that the effect of warming up differs

Data were analyzed using a general linear model between surgical levels (i.e. if warming up resulted in

testing. For all statistical analyses, a p-value less than 0.05 lower times for medical students, but did not make any

was considered statistically significant (Flow Chart 1). difference to time for surgeons). The interaction effect was

not significant in this model though, suggesting that the

RESuLTS effect of warming up was the same for medical students,

surgical trainees and surgeons.

Descriptive statistics were produced for each of the Post hoc comparisons of the surgical level group were

four response variables (time, acceleration, smoothness performed to compare mean times between the surgi-

and working areas) by surgical level (medical student, cal levels. This showed that surgeons had significantly

surgical trainee and surgeon) and warm-up. lower mean time than medical students (p = 0.0084) and

A general linear model was fit to test the effect of surgical trainees (p = 0.0072). There was no significant

surgical level and warm-up on each of the four response difference between mean time for surgical trainees and

variables. The results of the 4 models are summarized medical students (p = 0.9145) (Graph 1 and Table 2).

below (Table 1). Surgical level was a significant predictor of accelera-

Surgical level was a significant predictor of time when tion (p = 0.0004), While warm-up improved acceleration

controlling for warm-up (p = 0.0112). But warm-up was in all groups but warm-up was not clinically significant

not a significant predictor for time when controlling (p = 0.2157).

for surgical level (p = 0.9589). In other words, there is Post hoc comparisons of the surgical level group

evidence that surgical level has an effect on time. While

warm-up reduced the mean time of operation in surgeons showed surgeons had significantly lower mean accele-

and medical students group. But they were not to the ration than medical students (p = 0.0035) and surgical

level of clinically significant. trainees (p = 0.0001). There was no significant difference

between mean acceleration for surgical trainees and

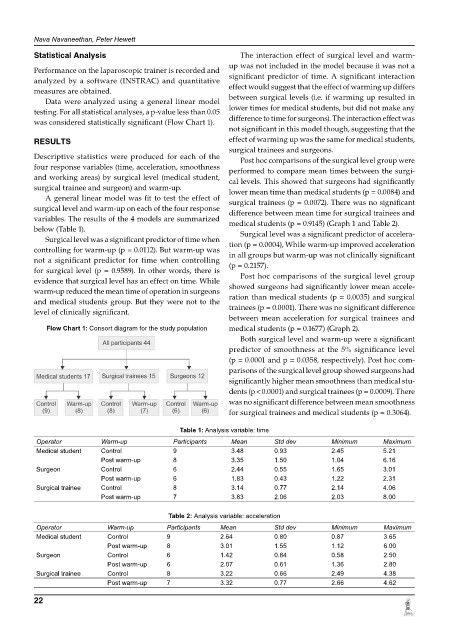

Flow Chart 1: Consort diagram for the study population medical students (p = 0.1677) (Graph 2).

Both surgical level and warm-up were a significant

predictor of smoothness at the 5% significance level

(p = 0.0001 and p = 0.0358, respectively). Post hoc com-

parisons of the surgical level group showed surgeons had

significantly higher mean smoothness than medical stu-

dents (p < 0.0001) and surgical trainees (p = 0.0009). There

was no significant difference between mean smoothness

for surgical trainees and medical students (p = 0.3064).

Table 1: Analysis variable: time

Operator Warm-up Participants Mean Std dev Minimum Maximum

Medical student Control 9 3.48 0.93 2.45 5.21

Post warm-up 8 3.35 1.50 1.04 6.16

Surgeon Control 6 2.44 0.55 1.65 3.01

Post warm-up 6 1.83 0.43 1.22 2.31

Surgical trainee Control 8 3.14 0.77 2.14 4.06

Post warm-up 7 3.83 2.06 2.03 8.00

Table 2: Analysis variable: acceleration

Operator Warm-up Participants Mean Std dev Minimum Maximum

Medical student Control 9 2.64 0.80 0.87 3.65

Post warm-up 8 3.01 1.55 1.12 6.00

Surgeon Control 6 1.42 0.84 0.58 2.50

Post warm-up 6 2.07 0.61 1.36 2.80

Surgical trainee Control 8 3.22 0.66 2.49 4.38

Post warm-up 7 3.32 0.77 2.66 4.62

22