Anatomy of Anterior Abdominal Wall

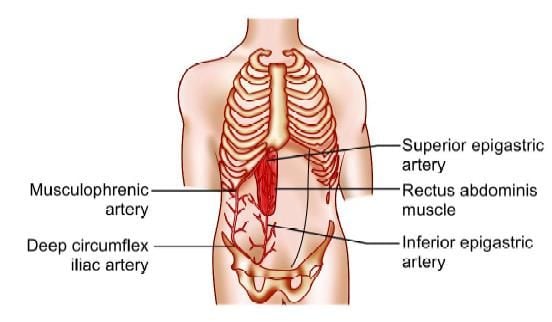

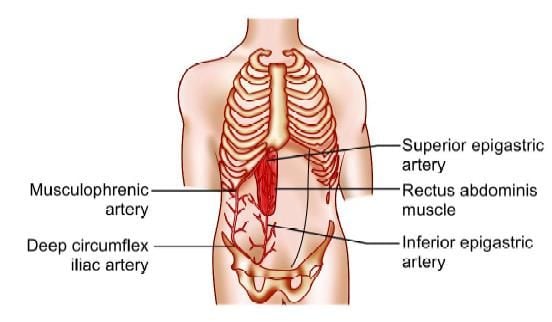

Knowledge of the surgical anatomy of the abdominal wall is essential for the safe access in laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic instruments traverse the skin, subcutaneous fat, variable myofascial layers, preperitoneal fat, and parietal peritoneum. There are three large, flat muscles (External oblique, internal oblique, and transverses abdominis) and one long vertically oriented segmental muscle (rectus abdominis) on each side. The layers of the abdominal wall in the midline include skin, subcutaneous fat, and a fascial layer (linea alba) that is a coalescence of the anterior and posterior rectus sheath. Four major arteries on each side are also present which form an anastomotic arcade that supplies the abdominal wall. The superior and inferior epigastric artery and the branches provide the major blood supply to the rectus abdominis muscle and other medial structures.

Among all these arteries, the most important for laparoscopic surgeon is the inferior epigastric artery and vein. The inferior epigastric vessels landmark is less variable compared to superior epigastric. Bleeding from inferior epigastric is a big problem because it is larger in diameter than superior epigastric.

Anterior abdominal wall anatomy

Umbilicus is the site of choice for access in majority of laparoscopic procedure. The umbilicus is a fusion of fascial layers and is devoid of subcutaneous fat. The median umbilical ligament which is obliterated urachus and paired medial umbilical ligaments ie, obliterated umbilical arteries are peritoneal folds that join at the inferior crease of the umbilicus, forming a tough layer. This umbilical tube scar remains after the umbilical cord obliterates which makes an attractive site of primary access of Veress Needle and trocar. At the level of umbilicus, skin fascia and peritoneum are fused together, with the minimum fat. The midline of abdominal wall is free of muscle fibers, nerves and vessels except at its inferior edge where pyramidalis muscle is sometimes found. Therefore, Veress needle or trocar insertion in these locations rarely cause much bleeding. If a defect in the umbilical fascia suggests an umbilical hernia or if any midline incision scar of previous laparoscopy is found or if any anomalies of the urachus may also exist umbilicus should not be used for primary access. If an umbilical hernia or urachal anomaly is suspected, alternative access sites may need to be considered.

The colon is attached to the lateral abdominal wall along both gutters and puncture laterally for secondary trocars should be under video control to avoid visceral injury. When left subcostal site is chosen for access it should be 2 cm below the costal margin in the midclavicular line called Palmer's point. The costal margin provides good resistance as the needle is introduced. When puncture site lateral to the midline is used, it is prudent to choose location lateral to the linea semilunaris to avoid injury of superior and inferior epigastric vessels. In obese patients, the linea semilunaris may not be visible. In these, location of inferior artery can be localized by careful transillumination.

Access to preperitoneal space is gained by penetrating almost all the layers of abdominal wall except peritoneum. The open technique of access is preferable in this situation. After incising the fascia with the scalpel, fingered dissection is advisable to avoid puncture of peritoneum.

Knowledge of the surgical anatomy of the abdominal wall is essential for the safe access in laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic instruments traverse the skin, subcutaneous fat, variable myofascial layers, preperitoneal fat, and parietal peritoneum. There are three large, flat muscles (External oblique, internal oblique, and transverses abdominis) and one long vertically oriented segmental muscle (rectus abdominis) on each side. The layers of the abdominal wall in the midline include skin, subcutaneous fat, and a fascial layer (linea alba) that is a coalescence of the anterior and posterior rectus sheath. Four major arteries on each side are also present which form an anastomotic arcade that supplies the abdominal wall. The superior and inferior epigastric artery and the branches provide the major blood supply to the rectus abdominis muscle and other medial structures.

Among all these arteries, the most important for laparoscopic surgeon is the inferior epigastric artery and vein. The inferior epigastric vessels landmark is less variable compared to superior epigastric. Bleeding from inferior epigastric is a big problem because it is larger in diameter than superior epigastric.

Anterior abdominal wall anatomy

Umbilicus is the site of choice for access in majority of laparoscopic procedure. The umbilicus is a fusion of fascial layers and is devoid of subcutaneous fat. The median umbilical ligament which is obliterated urachus and paired medial umbilical ligaments ie, obliterated umbilical arteries are peritoneal folds that join at the inferior crease of the umbilicus, forming a tough layer. This umbilical tube scar remains after the umbilical cord obliterates which makes an attractive site of primary access of Veress Needle and trocar. At the level of umbilicus, skin fascia and peritoneum are fused together, with the minimum fat. The midline of abdominal wall is free of muscle fibers, nerves and vessels except at its inferior edge where pyramidalis muscle is sometimes found. Therefore, Veress needle or trocar insertion in these locations rarely cause much bleeding. If a defect in the umbilical fascia suggests an umbilical hernia or if any midline incision scar of previous laparoscopy is found or if any anomalies of the urachus may also exist umbilicus should not be used for primary access. If an umbilical hernia or urachal anomaly is suspected, alternative access sites may need to be considered.

The colon is attached to the lateral abdominal wall along both gutters and puncture laterally for secondary trocars should be under video control to avoid visceral injury. When left subcostal site is chosen for access it should be 2 cm below the costal margin in the midclavicular line called Palmer's point. The costal margin provides good resistance as the needle is introduced. When puncture site lateral to the midline is used, it is prudent to choose location lateral to the linea semilunaris to avoid injury of superior and inferior epigastric vessels. In obese patients, the linea semilunaris may not be visible. In these, location of inferior artery can be localized by careful transillumination.

Access to preperitoneal space is gained by penetrating almost all the layers of abdominal wall except peritoneum. The open technique of access is preferable in this situation. After incising the fascia with the scalpel, fingered dissection is advisable to avoid puncture of peritoneum.