Role of Laparoscopic Surgery in Borderline Ovarian Tumor: An Overview

Dr Preeti Yadav

MBBS, MS

Formerly Senior Resident, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology,

Maulana Azad Medical College and Associated Lok Nayak Hospital,

New Delhi, India.

ABSTRACT

Borderline ovarian tumor (BOT) is a distinct variety of epithelial ovarian tumor with low malignant potential, which lies in middle of the spectrum from benign to malignant. Despite having some malignant potential, most of them presents at early stage, exhibiting slow progression and excellent prognosis. These subset of ovarian tumor presents with diagnostic difficulty and hence many treatment dilemmas. The affliction of younger women with BOT, adds to the confusion and controversies regarding appropriate treatment strategy. With advancing technology, minimum access surgery is increasingly becoming standard of care in gynaecological malignancies of uterus and cervix. Role of laparoscopy in benign ovarian pathologies is well established now and increasing reports of its role in early stage ovarian malignancies have been reported. Considering favourable prognosis of BOT, it is desirable to give the benefits of laparoscopy to patients especially with early stage disease. It is not associated with increased risk of recurrence. Laparoscopy is beneficial for young women, desirous of childbearing, who undergoes fertility sparing surgery. Several retrospective case series and reviews have demonstrated safety and efficacy of laparoscopy for management of BOT, when performed by a trained gynaecologic surgeon. This article reviews the literature for the justified role of laparoscopy, weighing all pros and cons in various scenarios encountered with BOT.

KEYWORDS: Laparoscopy, Borderline Ovarian Tumor, Fertility sparing surgery, Tumor spillage, Restaging, Recurrence

INTRODUCTION:

Borderline ovarian tumor(BOT) is a distinct well established yet controversial entity among ovarian tumors of epithelial origin, which is biologically and histopathologically intermediate between frankly malignant and obviously benign ovarian tumors. BOTs are also referred to as tumors of low malignant potential.[1] Although BOT has been acknowledged both by FIGO and WHO for more than 4 decades, still they are considered a controversial issue. There is no consensus on preoperative diagnosis of BOT, extent of surgical treatment needed, requirement of adjuvant treatment and postoperative follow up.

BOT is a different entity from ovarian malignancy as it more commonly occurs in younger age group, diagnosed at an early stage and holds better prognosis for the same stage disease. Many times fertility preservation is a crucial issue, where complete surgical resection is not always desirable, hence a different treatment strategy from that of malignancy should be considered.

In recent times laparoscopy has become the standard of care for benign adnexal masses and is feasible in uterine and cervical malignancies. In 1994 laparoscopy was first used in early ovarian cancer with good outcome.[2] In recent times, laparoscopy is being preferred by increasing number of patients in view of clear benefits such as lower morbidity (less pain, shorter hospital stay and lower risk of postoperative infection) and better cosmetic results.[3,4] Taking into account that BOTs commonly affect younger age group where fertility may be desired, and their limited malignant potential, laparoscopic resection may be considered surgical method of choice. The objective here is to review data from recent literature pertaining to laparoscopic approach for BOT and draw conclusions based on evaluation of these data.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of BOTs is approximately 1.8 to 4.8 per 100,000 women per year, and account for around 15-20% of epithelial ovarian tumors.[5,6] Although the incidence of ovarian malignancy is decreasing, the incidence of BOTs has been observed to increase worldwide in recent decades.[7,8] This may be due to more accurate pathological diagnosis, protective effect of oral contraceptive pills for malignant ovarian tumors only and contributory effect of fertility drugs on BOTs.[9] Patients with borderline ovarian tumors are 10 years younger than women with epithelial ovarian cancer (45 vs 55 years). One third to half of patients diagnosed with BOT are younger than 40 years of age and frequently are candidates for fertility-sparing surgery.[10] The prognosis for most patients with BOTs is excellent, with 5-year survival rate for stage I borderline tumors approximately 95%–97% and for stage II-III patients 65%–87% .[11]

HISTOLOGY

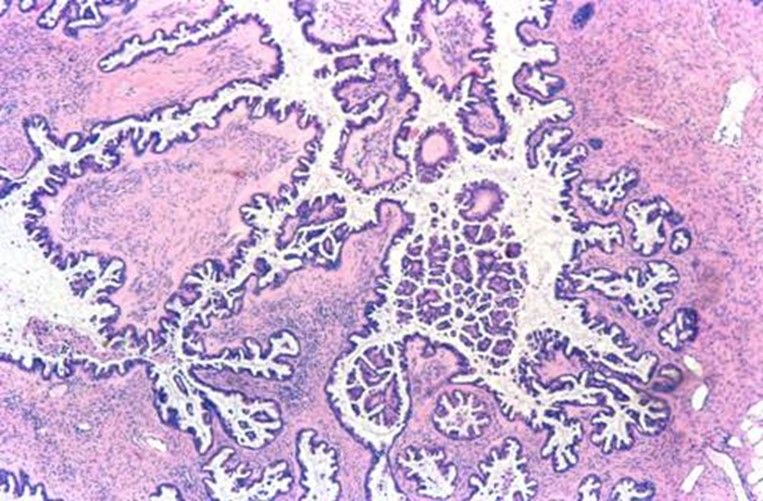

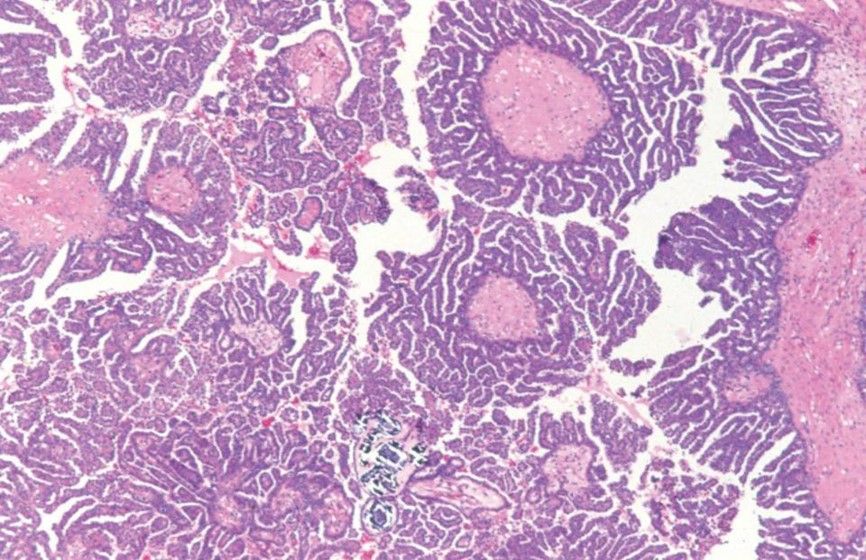

BOTs have been identified in all epithelial subtypes, including endometrioid, clear cell and Brenner (transitional cell), but serous (53.3%) and mucinous histologies (42.5%) are most common.[12] The distribution of the type of BOT shows geographical variation, serous being more common in western countries and mucinous more common in Asian countries. As defined by World Health Organization, histologically BOT exhibits atypical epithelial proliferation with mitotic figures greater than that seen in benign counterparts without destructive stromal invasion. Serous BOT are the most common type which further are of two subtypes, typical serous borderline tumor (90%) and serous borderline tumor with micropapillary pattern(10%).[13] The prognosis of stage 1 typical serous borderline tumors is excellent with 5 year survival of 98%. Even the advanced stage disease with noninvasive peritoneal implants have 5 year survival of 90%, which drops down to 66% in case of invasive implants. Typical serous BOTs are bilateral around 30% of the time. Serous BOTs with micro papillary pattern are more aggressive as suggested by increased incidence of microinvasion, peritoneal invasive impants (50%), surface involvement (50%), lymph node involvement, bilaterality (70%) and advanced stage at diagnosis.[14]

Mucinous variety is second most common type of BOT, which constitutes 10% of all mucinous tumors. They are classified as the intestinal type (85%) and the endocervical type (15%).[15] Intestinal mucinous BOTs occur in relatively older women (40 to 50 years old). They are usually unilateral, large (20-22cm), multilocular cysts, and in most cases are limited to the ovary. Endocervical mucinous BOTs, also referred to as mullerian or seromucinous tumors, occur in younger women (35 to 39 years old). They are relatively smaller (8 to 10 cm) macroscopically unilocular cystic tumors, and are more frequently bilateral (30%) as compared to intestinal variety.. Stage 2 and 3 mucinous BOTs are mostly endocervical type with relatively poor prognosis. With optimum staging and resection, prognosis of intestinal mucinous BOT is excellent in stage I tumor with recurrence rate of 9% in 5 years. Most recurrent cases are due to the possibility of sampling error at the histopathological examination. [15] Adequate pathologic sampling is mandatory to detect a small focus of carcinoma in cases of mucinous BOT as these are heterogeneous, and one tumor can show areas with benign, borderline and malignant features. At least two sections per centimeter are needed, specifically if the tumor is more than 10 cm[16]. Uncommon subtypes of borderline ovarian tumors encompass 3–4% of all BOTs. They include endometrioid, clear cell, transitional (Brenner) borderline tumors, or mixed epithelial tumors.

DIAGNOSIS (Preoperative & Intraoperative)

BOTs till date remains a diagnostic dilemma. They are correctly classified preoperatively only in 29%–69% of cases.[17] BOTs are difficult to classify using subjective evaluation by grayscale and Doppler ultrasound. On the contrary, sonography can accurately distinguish between benign and malignant ovarian tumors preoperatively and guide further operative plan.[17] But because of the overlapping features of BOTs with both benign and malignant tumors, its differentiation becomes difficult. Mucinous intestinal type BOTs are often misclassified as benign mucinous cystadenoma (16%). Micropapillary type of serous BOTs or endocervical type of mucinous BOTs are difficult to differentiate from invasive tumors on ultrasound. In the study by Sokalska et al, 24% (13/55 cases) of borderline tumors were presumed to be invasive ovarian tumors preoperatively.[18] No specific Doppler flow indices are defined currently to diagnose BOTs. The 3D grayscale ultrasound, providing details of the tumor vascular tree patterns, was also not found to be superior to the conventional 2D ultrasound.[19] Investigations based on morphological and vascular tree pattern assessment including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or even positron emission tomography also add very little to the accurate diagnosis of BOTs. One approach which could clinch the diagnosis is by performing both MRI and PET. Ovarian mass that shows complex features suggesting malignancy on MRI but appears benign on PET is strongly likely to be a BOT.[20]

The serum tumor marker CA125 is also of no help. In the systematic review by du Bois et al, of the 1,937 patients with borderline tumors CA125 was negative in 53.8%. [12] In IOTA trial, among 93 patients with BOT, 53% had lower CA125 levels than the cutoff of 35 u/ml. [21] Various indices like RMI (Risk of Malignancy Index) score, based on ultrasound findings and tumor markers are obviously of no diagnostic value. Diagnosis of BOT can be made by histopathology of fresh frozen section sent at the time of surgery but in approximately one third of the cases the diagnosis is revised after final histopathology report of the specimen. Most of the times they are underdiagnosed as benign ovarian tumors than being overdiagnosed.[12] The fresh frozen section is not specific in making the diagnosis of BOT as extensive specimen sampling is required to make the diagnosis.

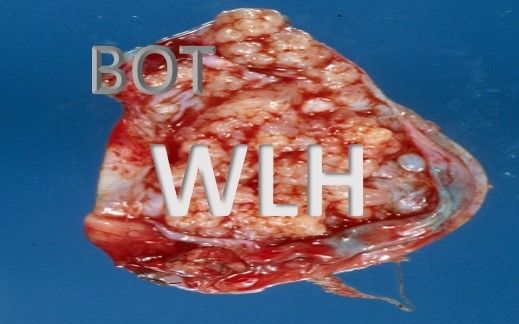

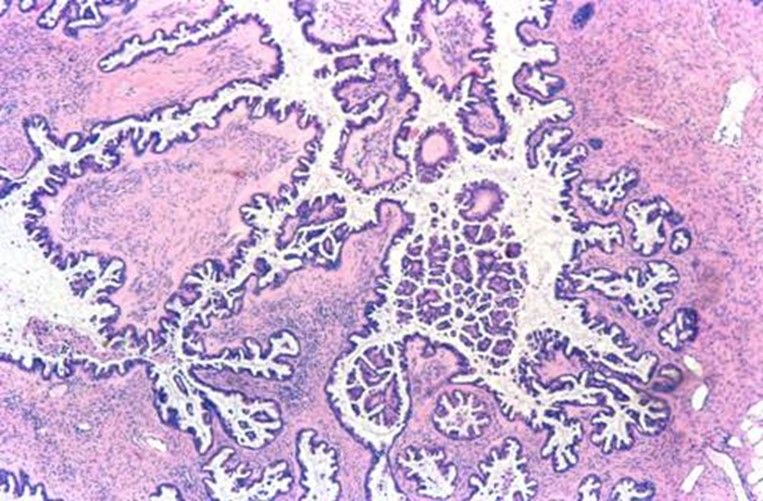

SEROUS BORDERLINE TUMOR

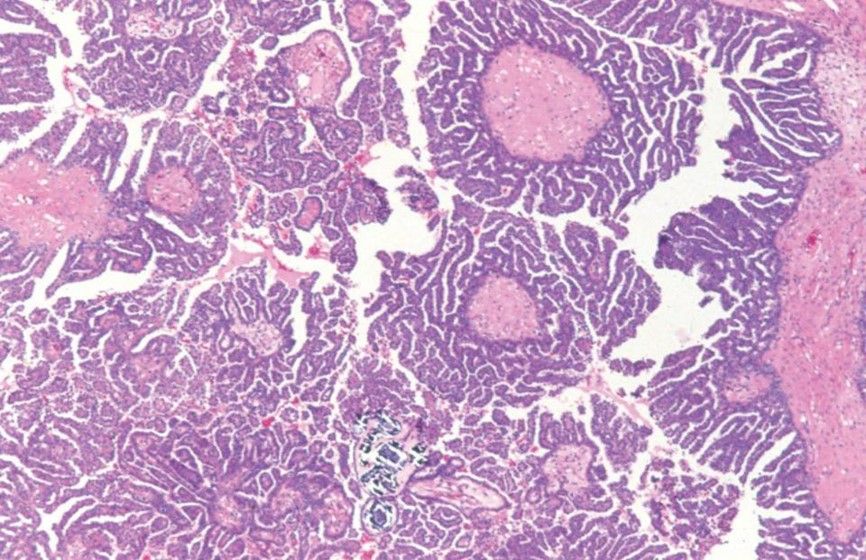

SEROUS BORDERLINE TUMOR WITH MICROPAPILLARY PATTERN

GROSS SPECIMEN OF SEROUS BOT

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

The staging of the BOTs is done in a similar manner as other ovarian tumours. In order to define the FIGO stages, the entire abdominal cavity must be thoroughly examined; peritoneal washing, hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo oophorectomy, and omentectomy must be performed; and all suspicious lesions must be excised during surgery.

The unresolved issues in management of BOTs are many, including need of lymphadenectomy, justification of fertility sparing surgery, postoperative fertility treatment, laparoscopy as the surgical approach, adjuvant chemotherapy and restaging surgery on incidental diagnosis of BOT.

Routine pelvic and paraaortic lymph node dissection is unnecessary for BOTs except in case of endocervical mucinous BOT. [22]

Fertility-sparing surgery refers to conserving the uterus, with one or both ovaries, during surgical staging. As BOTs are relatively prevalent among young women preserving fertility is often an important issue, which requires a careful approach. The literature available on follow up of these patients, give important source of information regarding the behaviour of BOTs undergoing conservative surgery. Recently published literature describes fertility-sparing surgery as a safe and effective treatment option for BOTs. [21] According to Trillsch et al., the recurrence rate following radical surgery was approximately 5%, whereas that following fertility-sparing surgery was higher at 10% to 20%. The recurrences do not necessarily lower the survival rate as they usually occur in the form of borderline histology. [23] Approximately 50% of BOT patients have natural pregnancies after fertility-sparing surgery. [10, 24] Therefore, this approach should be considered where fertility is desired.

Relapse is common when only cystectomy is done, so oophorectomy should always be the choice unless tumor is bilateral and fertility is desired. In such patients, bilateral oophorectomy with conservation of uterus for subsequent frozen embryo transfer should be considered as another option. And if fertility-sparing surgery with preservation of functioning ovarian parenchyma is performed, extensive sampling of the resection margins of the removed ovarian cyst is very important. [10] Exception to this is mucinous BOT, where complete ovarian cystectomy should always be done, considering high chances of recurrence in malignant form. [25]

LAPAROTOMY VS LAPAROSCOPY

Traditionally, as in malignancy, laparotomy has been the surgical mode of choice for BOT. In recent past, more and more benign ovarian tumors are being operated by laparoscopy and is now considered the standard of care for the same. As it is difficult to diagnose BOTs preoperatively and intraoperatively, they are often underdiagnosed as benign ovarian tumours, only to be identified as BOTs on final histopathology report. Consequently increasing number of cases have been reported with BOT being managed with laparoscopy. This seems to be an attractive approach as it is associated with less postoperative morbidity and peritoneal adhesion formation. The latter may theoretically prove beneficial for preserving fertility.

With new advances in laparoscopic instruments and techniques, staging of BOTs is increasingly being performed laparoscopically. The procedure included are the same as in laparotomy, including tumor debulking (hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy), random and targeted peritoneal biopsies, peritoneal washings, and infracolic omentectomy.

The outcome and feasibility of laparoscopy over laparotomy has been evaluated mainly in retrospective studies. In a retrospective multicentric study by Fauvet et al, 147 patients with BOT were managed laparoscopically. 42 patients required laparoconversion and rest 107 patients were managed with laparoscopy alone. 97.9% of the patients undergoing laparoscopy had stage 1 disease as compared to 88.5% patients undergoing laparotomy. Proportion of conservative surgeries performed was higher in laparoscopy group. Patients were followed for a mean period of 27.5 months. They reported 100% survival and recurrence in 13 patients, which was not significantly different from laparotomy group. More frequent cyst rupture and lower rate of complete surgical staging was seen in laparoscopy. Cyst rupture was usually related to cystectomy. No port site metastasis was reported. They concluded that laparoscopy is an alternative to laparotomy for treatment of BOT, with strict adherence to surgical staging guidelines. [26]

Another retrospective study by Romagnolo et al, included 113 patients with BOTs, of whom 52 were treated by laparoscopy and 61 underwent laparotomy. After the mean follow up for 44 months, no difference was observed in progression free survival between the 2 groups. [27] They also concluded that laparoscopic surgery may be the treatment of choice for BOT.

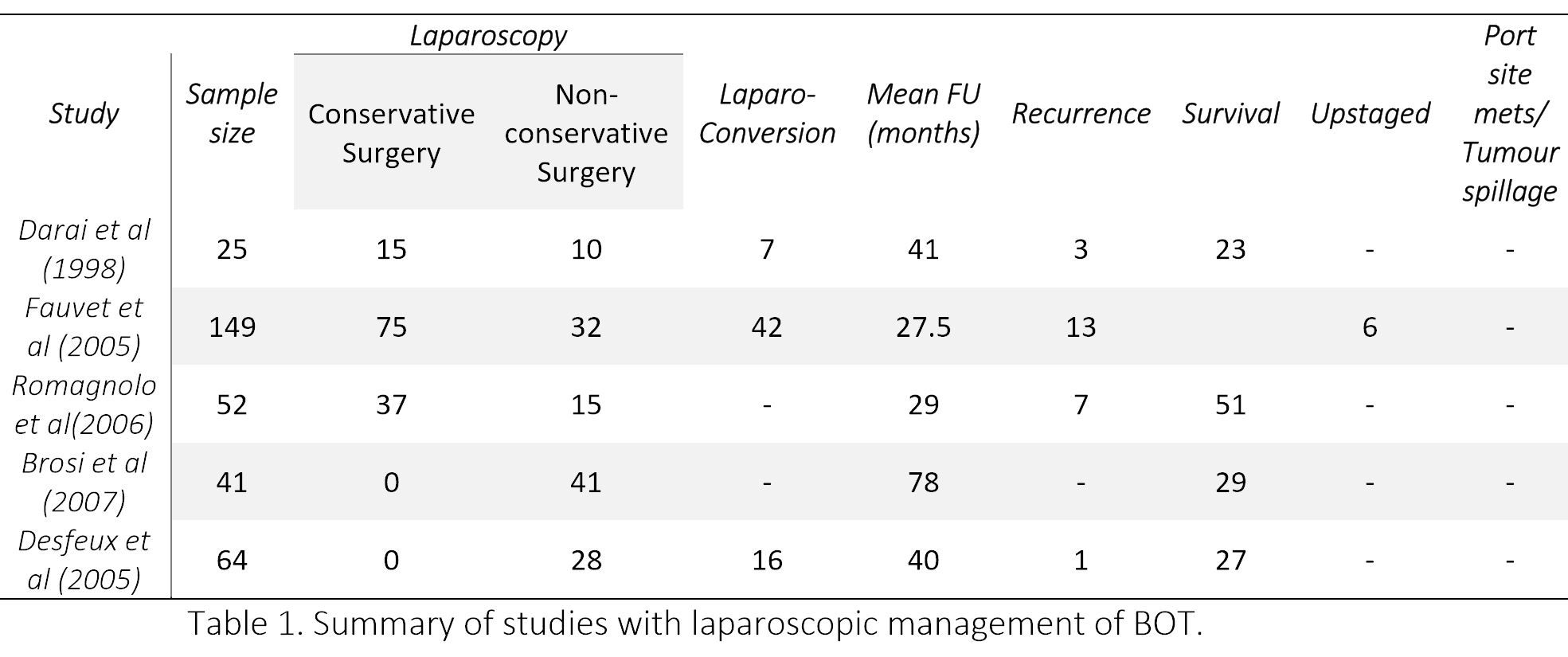

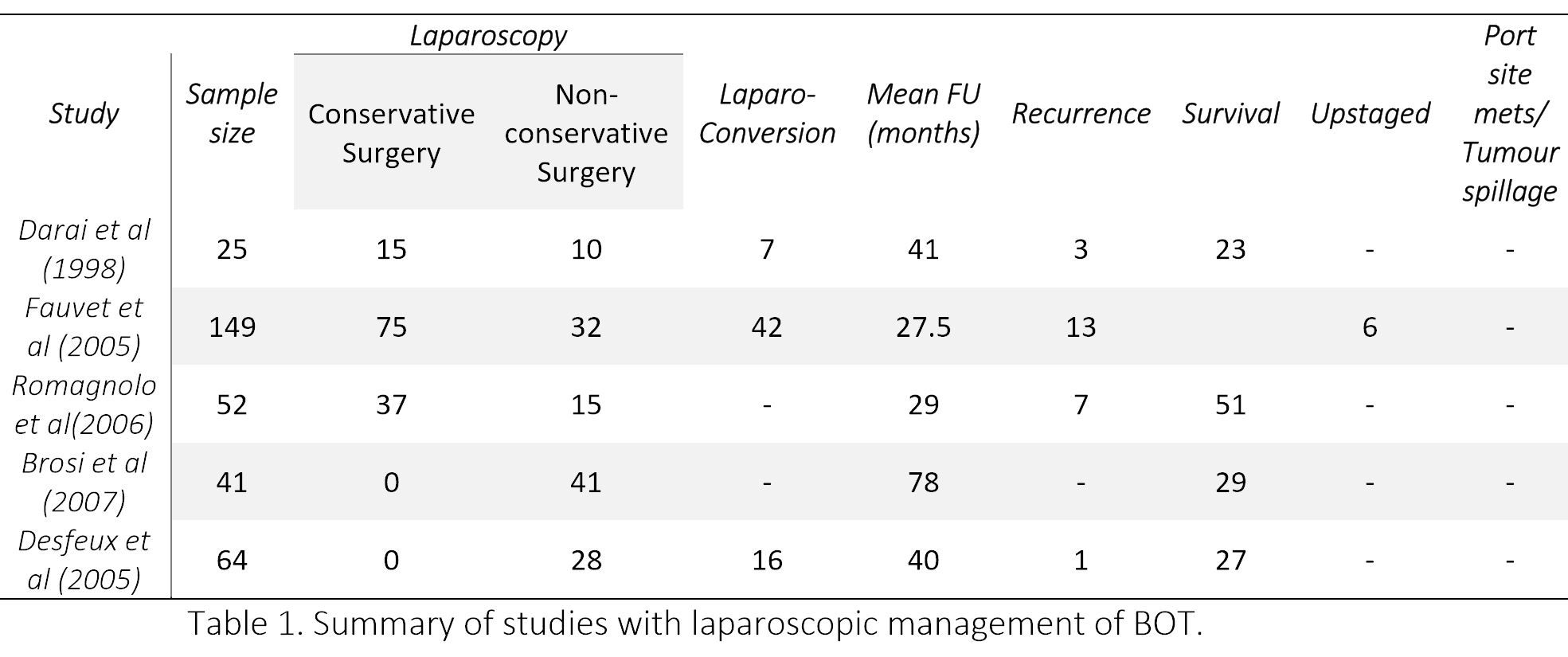

Later few more studies concluded that if a strict management protocol is followed, minimal access surgery is feasible, safe and can prove to be effective in treatment of BOTs. [28,29] Brosi et al, in the longest documented follow-up (78 months) reported a survival of 100%. [28] However, 17% patient were lost to follow up. The various studies on laparoscopic management of BOTs have been summarized in Table 1. Although no randomized controlled study is available, still it can be concluded from the above data that laparoscopy is safe for BOT if appropriate staging is performed.

LAPAROSCOPY FOR FERTILITY SPARING SURGERY

Conservative surgery for early BOTs is considered safe, though a higher recurrence rate was observed after laparoscopically performed conservative surgery than after a laparotomy (14.9 vs. 7.7%). [12] But this was not confirmed by two multicenter studies, according to which surgical approach (laparoscopy vs laparotomy) did not seem to influence the progression free interval and rate of relapse, rather it depends upon extent of surgical resection. [26,27] Laparoscopy seems to be an attractive approach as it is associated with less postoperative adhesion formation compared with laparotomy, which may theoretically preserve fertility.

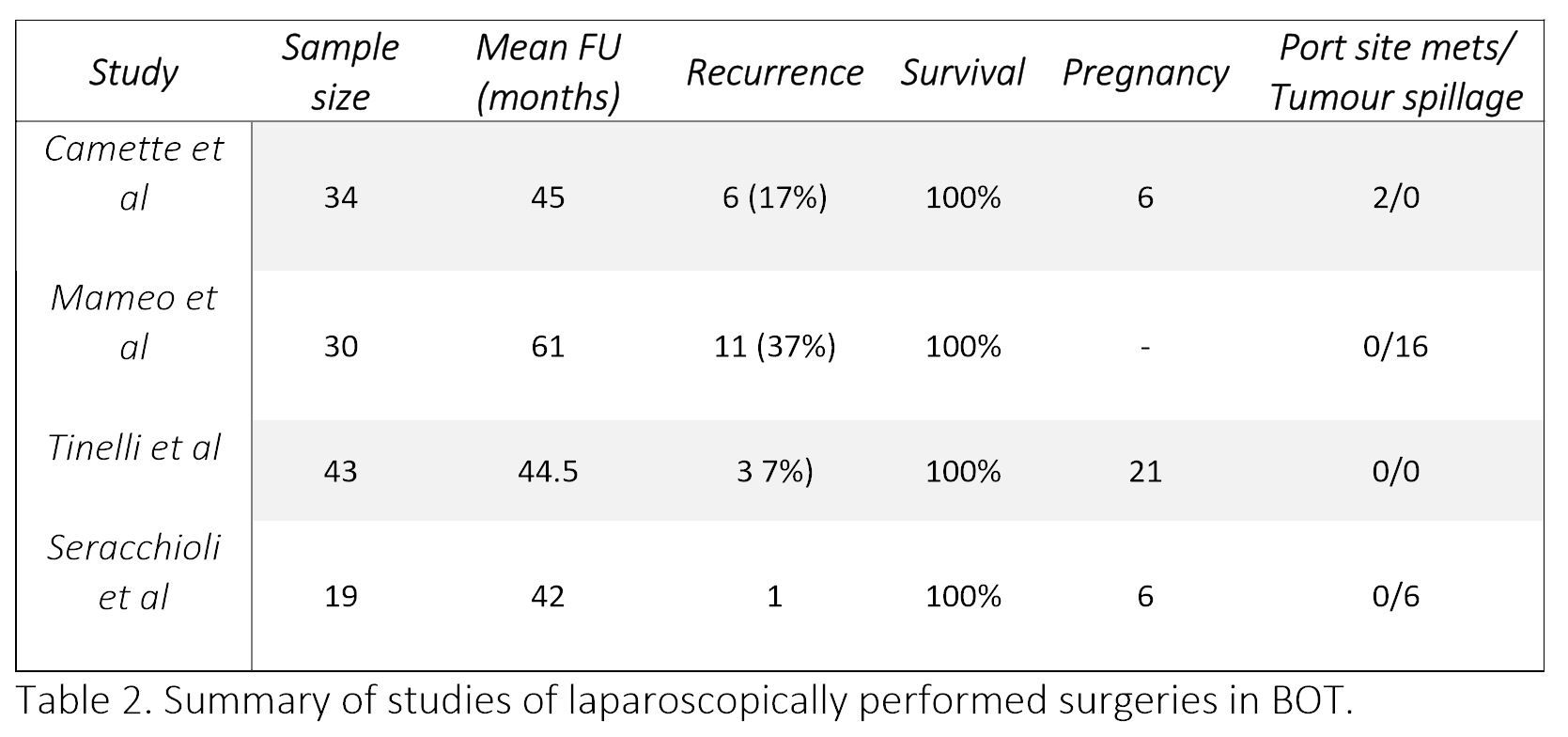

Camatte et al [30] presented a series of 34 patient who were intentionally treated with laparoscopy for BOT. 31 among them had fertility sparing conservative surgery. It was concluded that conservative laparoscopic treatment can safely be performed in young patients with early stage BOT. With a median follow-up for 45 months (range 6–228), 6 (17%) patients had recurrence of BOT (none had ovarian malignancy), and two port-site metastases were observed. Spontaneous conception occurred in 6 out of 15 patients desiring pregnancy.

Maneo et al [31] evaluated 62 patients with BOT undergoing fertility sparing surgery, of which 30 were operated laparoscopically, and 32 by laparotomy. Recurrence rate was 37% (11 cases) at a mean follow up of 61 months. They concluded that the diameter of the cyst is a significant factor to predict failure of laparoscopy, with a greater risk of rupture or persistence of the tumour in masses larger than 5 cm.

Tinelli et al [32] studied 43 women with BOT who underwent laparoscopic conservative surgery. At a mean follow up of 44 months, 3 patients (7%) developed recurrences (2 occurred after cystectomy and 1 after oophorectomy). Recurrences did not occur in the cases of intraoperative rupture of cyst. 21 women (49%) became pregnant during the follow-up period.

Seracchioli et al [33] treated 19 women of reproductive age by laparoscopic cystectomy or unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. On a mean follow up of 42 months, 1 patient had a recurrence in the same ovary. This was treated with repeat cystectomy. 6 women became pregnant on follow up.

Romagnolo et al [27] observed relapse rate of 7% for radical and 17% for conservative therapy. They suggested that progression free survival is a function of the extent of sugery performed rather than the mode of surgery.

Zanetta et al [34] noted recurrence rate of 15.2% and 2.5%, respectively, after conservative and radical surgery for stage I disease, and, 40% and 12.9% for stage II disease. They also concluded that conservative approach is reasonable in some cases, and should be followed by definitive surgery after successful pregnancies.

Recurrence rates vary regardless of the surgical approach: salpingo-ophrectomy recurrence rates range from 0% to 10%, cystectomy recurrence rates range from 12% to 58%, and radical surgery recurrence rates range from 2.5% to 5.7% [35, 36].

An important concern in cases managed with conservative surgery is the follow up. No uniform guidelines and recommendations are available. After evaluating physical examination, pelvic ultrasonography, and CA125 levels Zanetta et al [37] concluded that all three modalities together would seem to be the most prudent approach, TVS being the single best investigation for detection of relapse.

All laparoscopic procedures should nevertheless be performed by oncologic surgeons trained in extensive laparoscopic procedures in order to obtain optimal surgical staging, complete debulking, and better results in terms of both relapse free survival and fertility preservation rate [27].

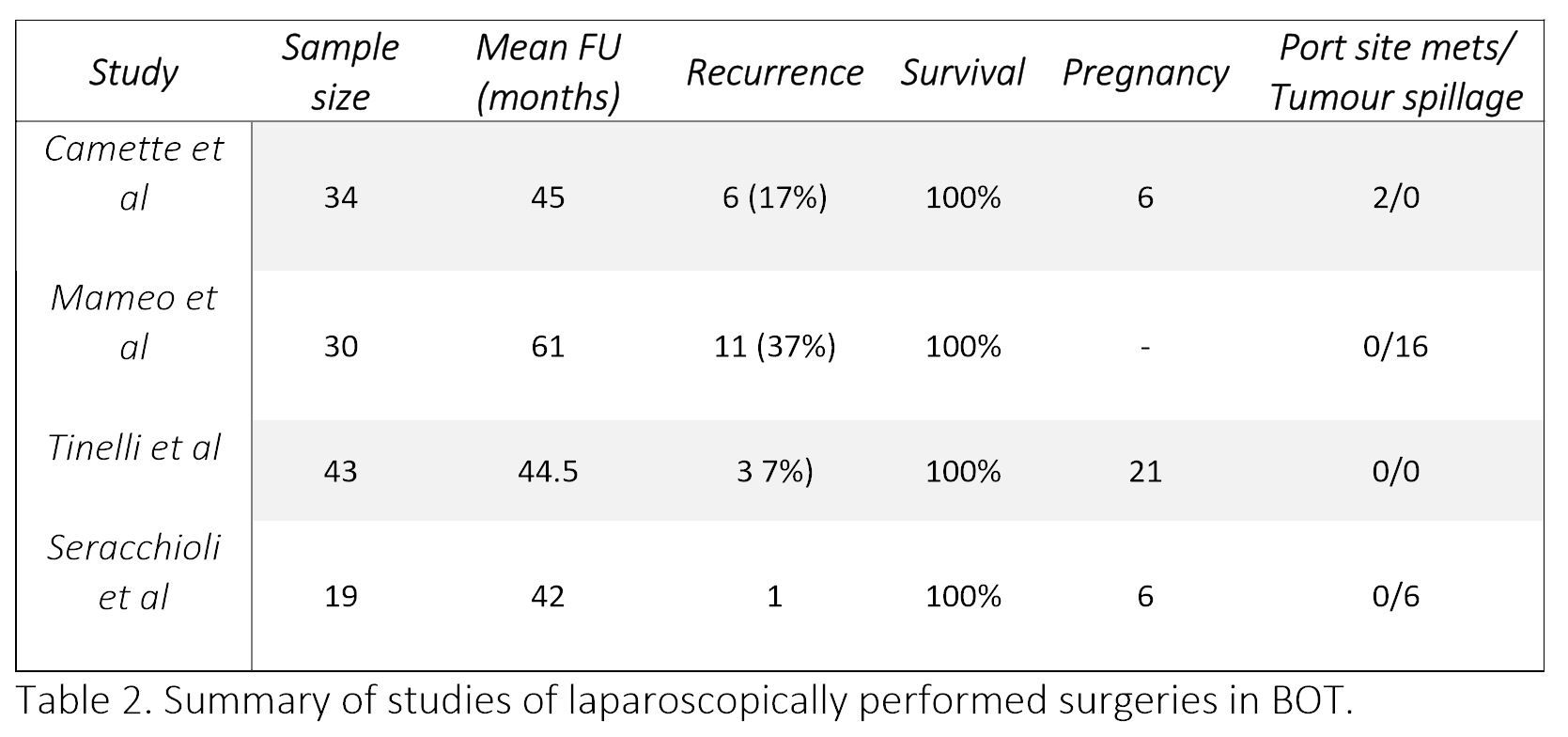

Table 2. Summary of studies of laparoscopically performed surgeries in BOT.

ACCIDENTALLY ENCOUNTERED BOT AFTER LAPAROSCOPY

The incidence of unexpected malignancy encountered after laparoscopy may vary depending on surgeons patients selection for laparoscopy. When done for sonologically benign looking adenexal mass, the rate of unexpected malignancy including BOT, after laparoscopy is expected to be 0–2.5%. [38,39]

A correct preoperative diagnosis of BOT is made only in 30 to 60% of patients, most of them are underdiagnosed as benign ovarian tumor. Shegiko et al [39] repoted 6 cases of BOT among 471 laparoscopically performed surgeries for benign tumors (1.2%). The cases had been followed for minimum of 24 months and maximum of 120 months, with no evidence of relapse. Restaging was not performed in any of the case.

As reported by Matsushita and colleagues [40], among presumably benign 1128 adnexal masses resected laparoscopically, 7 BOTs and 6 malignancies were diagnosed on final histopathology report. In all 13 cases (1.5%) sonology and CA125 were suggestive of benign pathology. They employed fresh frozen section in select cases. Nine patients were upstaged to Stage IC due to intraoperative tumour spillage. After a mean follow up of 38 months, all patients were alive and without recurrence.

RESTAGING

In the study by Shegiko et al, none of the 6 patients with BOT underwent second restaging surgery, with no recurrence reported in follow up period. [40] Matsushita et al, found no malignant tissue after restaging surgery performed in 8 of the 13 patients (61.5%). [40] Hence according to the current evidence, restaging can be avoided in incidentally found early stage BOT. However, these patients should be kept under close follow up.

CONCERNS IN LAPAROSCOPY

Concerns over implementing laparoscopy for BOTs include tumor spillage during surgery, port site metastasis, and chances of incomplete staging, all could potentially results in recurrence. As per the recent FIGO staging, early ovarian tumor (1a and 1b) if gets spilled intraoperatively, the disease is upstaged to 1c. Because of difficult tissue retrieval and dissection techniques in laparoscopy, tumor spillage is common. Nonetheless, the issue of tumor spillage influencing prognosis in early ovarian malignancy is controversial. Even though several recent studied suggests that tumor spillage in early BOT may not affect the prognosis, [41] all care and precaution should be taken to avoid the same. Another concern is the port site metastasis. Port site metastasis after laparoscopic treatment for BOT has been rarely reported. Of the 9 reported cases, surgical excision was performed with a 100% overall survival at 6 to 72 months of follow-up.[42] It is an uncommon complication after laparoscopic surgery for gynecologic malignancies(1-2%) and further rarer for BOT.[26,43]

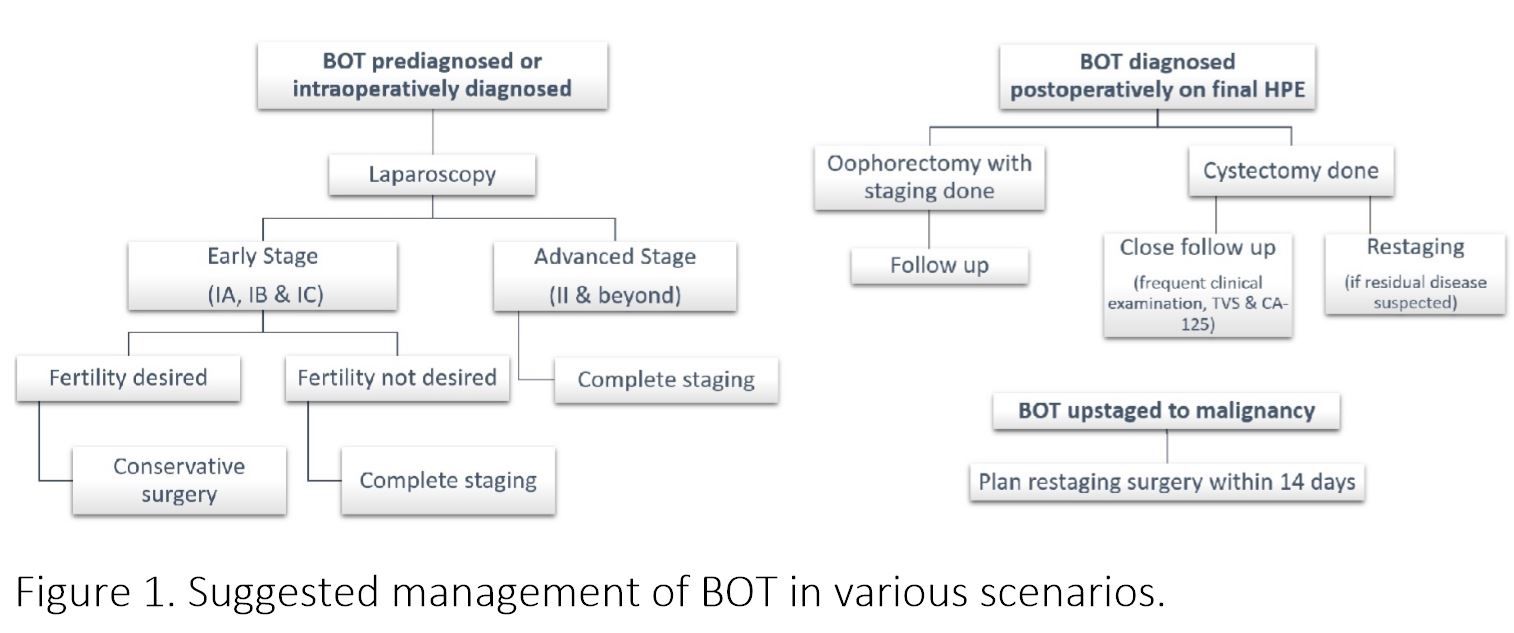

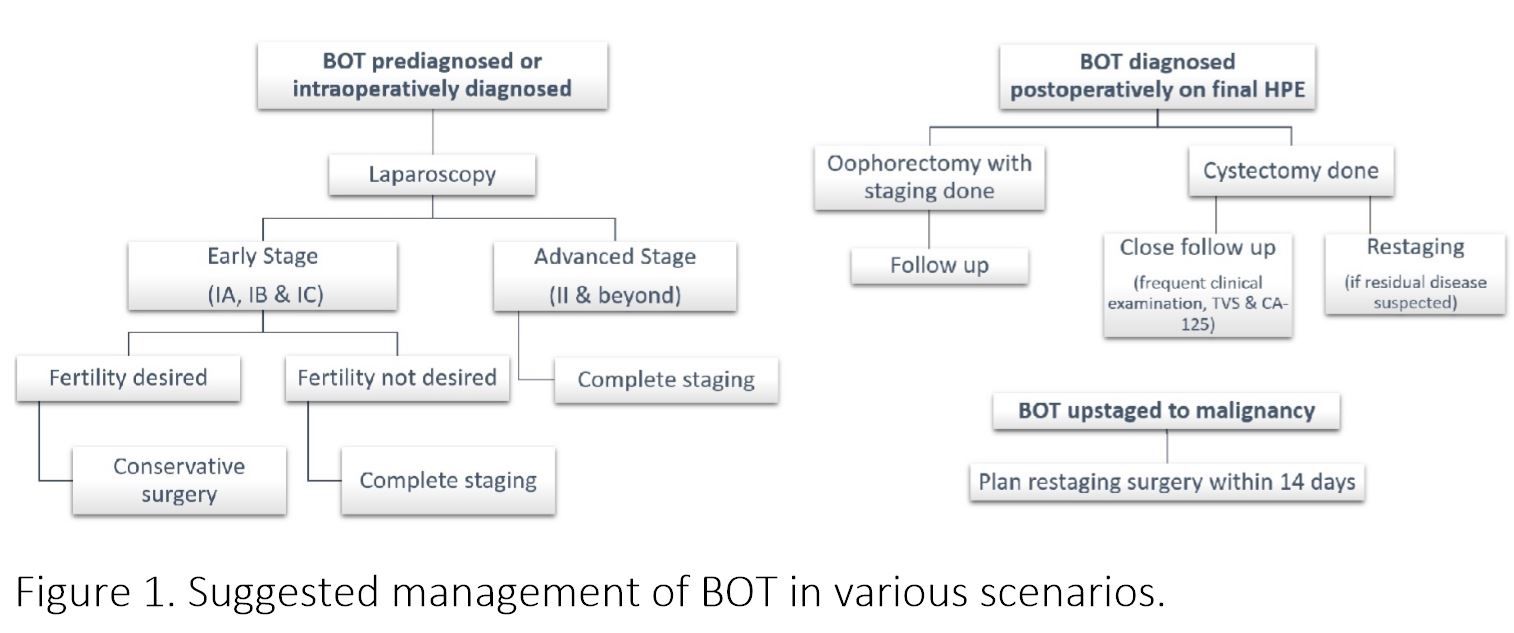

Figure 1. Suggested management of BOT in various scenarios.

CONCLUSION

BOT is an interesting entity amongst ovarian malignancies, more commonly afflicting relatively young females, showing indolent course and excellent prognosis. Laparoscopic treatment is an attractive alternative to laparotomy which has been proved to be an appropriate and reasonable therapeutic option, especially for early stage BOT. Laparoscopy can be very satisfying for the patient, provided care is taken regarding few things. A systematic evaluation of peritoneum for tumor deposits should be performed, resection of all the deposits should be done, in absence of the same random biopsies are to be taken. Ascitic fluid when present or peritoneal washing for cytology to be collected. The tumor and the peritoneal implants should always be subjected to histopathological examination by fresh frozen sample and close communication with pathologist should be maintained. In case of serous multipapillary BOT, invasive implants, frank malignancy complete resection with lymphadenectomy is required. For tissue retrieval endobag should be used, all efforts should be made to reduce the risk of rupture inside peritoneal cavity and port site metastasis. If the tumor gets ruptured, thorough peritoneal lavage and port site should be cleaned with heparinized saline or povidon iodine. After reviewing the literature, it can very well be concluded that conservative fertility surgery can be performed where desired. Laparoscopy, with careful selection of patients, proves beneficial in fertility preservation as there are less adhesion formation. But taking into account the higher rates of recurrence, patients undergoing fertility sparing surgery must be regularly followed up with clinical examination, transvaginal ultrasound and CA125, for early identification of recurrence. After reviewing the literature it is clear that recurrence is more after cystectomy irrespective of the route, hence it should be reserved only in cases with single involved ovary of bilateral involvement where future childbearing is desired. Also for any stage of BOT no less surgery than bilateral salpingo-ophorectomy should be performed after the age of 40 years. In my opinion when conservative surgery is done second surgery should be planned for completion of the procedure of staging, once the family is completed. Laparoscopic surgery is appropriate option in patients with early stage BOT. Advanced stage, which is rare presentation in BOT can be managed laparoscopically only in expert hands, if adequate staging seems feasible. With advantages over laparotomy like

shorter hospitalizations, lower blood loss, improved visualization, a reduction in need for postoperative analgesics, less morbidity, and more rapid recovery, it should always be considered in managing BOT.

REFERRENCES

1) Sutton GP. Ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. In: Rubin SC, Sutton GP, editors. Ovarian cancer. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. p. 399-417.

2) Querleu D, Leblanc E. Laparoscopic infrarenal para-aortic lymph node dissection for restaging of carcinoma of the ovary or fallopian tube. Cancer 1994;73:1467–71.

3) Tozzi R, Kohler C, Ferrara A, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of early ovarian cancer: surgical and survival outcomes. Gynecologic oncology 2004;93:199-203

4) Lee M, Kim SW, Paek J, et al. Comparisons of surgical outcomes, complications, and costs between laparotomy and laparoscopy in early-stage ovarian cancer. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society 2011;21:251-6.

5) Skirnisdottir I, Garmo H, Wilander E, Holmberg L. Borderline ovarian tumors in Sweden 1960-2005: trends in incidence and age at diagnosis compared to ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer 2008;123:1897-901.

6) Sherman ME, Berman J, Birrer MJ, Cho KR, Ellenson LH, Gorstein F, et al. Current challenges and opportunities for research on borderline ovarian tumors. Hum Pathol 2004;35:961-70

7) Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P et al. Carcinoma of the ovary. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2006;95(suppl 1):S161–S192.

8) Bjorge T, Engeland A, Hansen S et al. Trends in the incidence of ovarian cancer and borderline tumours in Norway, 1954 –1993. Int J Cancer 1997;71:780 –786.

9) van Leeuwen FE, Klip H, Mooij TM et al. Risk of borderline and invasive ovarian tumours after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization in a large Dutch cohort. Hum Reprod 2011;26:3456 –3465.

10) Morice P. Borderline tumours of the ovary and fertility. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:149 –158.

11) Trope C, Davidson B, Paulsen T et al. Diagnosis and treatment of borderline ovarian neoplasms “the state of the art.” Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2009;30:471– 482.

12) du Bois A, Ewald-Riegler N, du Bois O et al. Borderline tumors of the ovary: A systematic review. Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2009;69:807– 833.

13) Lee KR, Tavassoli FA, Prat J et al. Tumours of the ovary and peritoneum. In Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2003:113–202.

14) Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim KR, Kim YT, et al. Micropapillary pattern in serous borderline ovarian tumors: does it matter? Gynecol Oncol 2011;123:511-6.

15) Koskas M, Uzan C, Gouy S, Pautier P, Lhomme C, HaieMeder C, et al. Prognostic factors of a large retrospective series of mucinous borderline tumors of the ovary (excluding peritoneal pseudomyxoma). Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:40-8.

16) Seidman JD, Khedmati F, Yemelyanova AV. Ovarial low grade serous neoplasm: Evaluation of sampling recommendations based on tumors expected to have invasion (those with peritoneal invasive low grade serous carcinoma (invasive implants)). Mod Pathol 2009;22(suppl 1):Abstract 236A.

17) Yazbek J, Ameye L, Timmerman D et al. Use of ultrasound pattern recognition by expert operators to identify borderline ovarian tumors: A study of diagnostic performance and interobserver agreement. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010;35:84–88.

18) Sokalska A, Timmerman D, Testa AC et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound examination for assigning a specific diagnosis to adnexal masses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009;34:462–470.

19) Alcazar JL, Jurado M. Three-dimensional ultrasound for assessing women with gynecological cancer: A systematic review. Gynecol Oncol 2011;120:340–346.

20) Lalwani N, Shanbhogue AK, Vikram R, Nagar A, Jagirdar J, Prasad SR (2010) Current update on borderline ovarian neoplasms. AJR American journal of roentgenology 194: 330–336.

21) Uzan C, Kane A, Rey A, Gouy S, Duvillard P, Morice P. Outcomes after conservative treatment of advanced-stage serous borderline tumors of the ovary. Ann Oncol 2010;21:55-60.

22) Rao GG, Skinner E, Gehrig PA, Duska LR, Coleman RL, Schorge JO. Surgical staging of ovarian low malignant potential tumors. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:261–6.

23) Trillsch F, Mahner S, Ruetzel J, Harter P, Ewald-Riegler N, Jaenicke F, et al. Clinical management of borderline ovarian tumors. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2010;10:1115-24.

24) Tinelli FG, Tinelli R, La Grotta F, Tinelli A, Cicinelli E, Schonauer MM. Pregnancy outcome and recurrence after conservative laparoscopic surgery for borderline ovarian tumors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:81-7.

25) Koskas M, Uzan C, Gouy S et al. Prognostic factors of a large retrospective series of mucinous borderline tumors of the ovary (excluding peritoneal pseudomyxoma). Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:40–48.

26) Fauvet R, Boccara J, Dufournet C et al. Laparoscopic management of borderline ovarian tumors: Results of a French multicenter study. Ann Oncol 2005;16: 403–410.

27) Romagnolo C, Gadducci A, Sartori E et al. Management of borderline ovarian tumors: Results of an Italian multicenter study. Gynecol Oncol 2006;101:255–260.

28) Brosi N, Deckardt R. Endoscopic surgery in patients with borderline tumor of the ovary: a follow-up study of thirty-five patients. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:606–609.

29) Desfeux P, Camatte S, Chatellier G, Blanc B, Querleu D, Lecuru F. Impact of surgical approach on the management of macroscopic early ovarian borderline tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;98:390–395.

30) Camatte S, Morice P, Atallah D, et al. Clinical outcomes after laparoscopic pure management of borderline ovarian tumors: results of a series of 34 patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:605–609.

31) Maneo A, Vignali M, Chiari S, et al. Are borderline tumours of the ovary safely treated by laparoscopy? Gynecologic oncology. 2004;94:387-92.

32) Tinelli FG, Tinelli R, La Grotta F, Tinelli A, Cicinelli E, Schonauer MM. Pregnancy outcome and recurrence after conservative laparoscopic surgery for borderline ovarian tumors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:81-7.

33) Seracchioli R, Venturoli S, Colombo FM, Govoni F, Missiroli S, Bagnoli A. Fertility and tumor recurrence rate after conservative laparoscopic management of young women with early-stage borderline ovarian tumors. Fertil Steril 2001;76:999–1004.07;86:81–7.

34) Zanetta G, Rota S, Chiari S, Bonazzi C, Bratina G, Mangioni C. Behavior of borderline tumors with particular interest to persistence, recurrence, and progression to invasive carcinoma: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:2658–64.

35) Cadron I, Leunen K, Van Gorp T, Amant F, Neven P, Vergote I. Management of borderline ovarian neoplasms. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25: 2928–2937.

36) Boran N, Cil AP, Tulunay G, Ozturkoglu E, Koc S, Bulbul D, et al. Fertility and recurrence results of conservative surgery for borderline ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:845–51.

37) Zanetta G, Rota S, Lissoni A. Ultrasound, physical examination, and CA125 measurement for the detection of recurrence after conservative surgery for early borderline ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol 2001;81: 63–6.

38) MuziiL, AngioliR, ZulloM, PaniciPB. The unexpected ovarian malignany found during operative laparoscopy: incidence, management, and implications for prognosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2005;12:81–89; quiz 90–81.

39) Saito S, kajiyama H, Miwa Y, Mizuno M, Kikkawa F, Tanaka S, Okomoto T.Unexpected ovarian malignancy found after laparoscopic surgery in patients with adnexal masses–a single institutional experience. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014; 76: 83-90.

40) Matsushita H, Watanabe K, Yokoi T, Wakatsuki A. Unexpected ovarian malignancy following laparoscopic excision of adenexal masses. Human Reproduction. 2014; 29(9): 1912-7.

41) Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Suzuki S, Ino K, Nawa A, Kawai M, Nagasaka T, Kikkawa F (2010) Fertilitysparing surgery in young women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. European journal of surgical oncology: the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology 36: 404–408.

42) Morice P, Camatte S, Larregain-Fournier D, Thoury A, Duvillard P, Castaigne D. Port-site implantation after laparoscopic treatment of borderline ovarian tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1167–1170.

43) Ramirez PT, Wolf JK, Levenback C. Laparoscopic port-site metastases: etiology and prevention. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:179–89

MBBS, MS

Formerly Senior Resident, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology,

Maulana Azad Medical College and Associated Lok Nayak Hospital,

New Delhi, India.

ABSTRACT

Borderline ovarian tumor (BOT) is a distinct variety of epithelial ovarian tumor with low malignant potential, which lies in middle of the spectrum from benign to malignant. Despite having some malignant potential, most of them presents at early stage, exhibiting slow progression and excellent prognosis. These subset of ovarian tumor presents with diagnostic difficulty and hence many treatment dilemmas. The affliction of younger women with BOT, adds to the confusion and controversies regarding appropriate treatment strategy. With advancing technology, minimum access surgery is increasingly becoming standard of care in gynaecological malignancies of uterus and cervix. Role of laparoscopy in benign ovarian pathologies is well established now and increasing reports of its role in early stage ovarian malignancies have been reported. Considering favourable prognosis of BOT, it is desirable to give the benefits of laparoscopy to patients especially with early stage disease. It is not associated with increased risk of recurrence. Laparoscopy is beneficial for young women, desirous of childbearing, who undergoes fertility sparing surgery. Several retrospective case series and reviews have demonstrated safety and efficacy of laparoscopy for management of BOT, when performed by a trained gynaecologic surgeon. This article reviews the literature for the justified role of laparoscopy, weighing all pros and cons in various scenarios encountered with BOT.

KEYWORDS: Laparoscopy, Borderline Ovarian Tumor, Fertility sparing surgery, Tumor spillage, Restaging, Recurrence

INTRODUCTION:

Borderline ovarian tumor(BOT) is a distinct well established yet controversial entity among ovarian tumors of epithelial origin, which is biologically and histopathologically intermediate between frankly malignant and obviously benign ovarian tumors. BOTs are also referred to as tumors of low malignant potential.[1] Although BOT has been acknowledged both by FIGO and WHO for more than 4 decades, still they are considered a controversial issue. There is no consensus on preoperative diagnosis of BOT, extent of surgical treatment needed, requirement of adjuvant treatment and postoperative follow up.

BOT is a different entity from ovarian malignancy as it more commonly occurs in younger age group, diagnosed at an early stage and holds better prognosis for the same stage disease. Many times fertility preservation is a crucial issue, where complete surgical resection is not always desirable, hence a different treatment strategy from that of malignancy should be considered.

In recent times laparoscopy has become the standard of care for benign adnexal masses and is feasible in uterine and cervical malignancies. In 1994 laparoscopy was first used in early ovarian cancer with good outcome.[2] In recent times, laparoscopy is being preferred by increasing number of patients in view of clear benefits such as lower morbidity (less pain, shorter hospital stay and lower risk of postoperative infection) and better cosmetic results.[3,4] Taking into account that BOTs commonly affect younger age group where fertility may be desired, and their limited malignant potential, laparoscopic resection may be considered surgical method of choice. The objective here is to review data from recent literature pertaining to laparoscopic approach for BOT and draw conclusions based on evaluation of these data.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of BOTs is approximately 1.8 to 4.8 per 100,000 women per year, and account for around 15-20% of epithelial ovarian tumors.[5,6] Although the incidence of ovarian malignancy is decreasing, the incidence of BOTs has been observed to increase worldwide in recent decades.[7,8] This may be due to more accurate pathological diagnosis, protective effect of oral contraceptive pills for malignant ovarian tumors only and contributory effect of fertility drugs on BOTs.[9] Patients with borderline ovarian tumors are 10 years younger than women with epithelial ovarian cancer (45 vs 55 years). One third to half of patients diagnosed with BOT are younger than 40 years of age and frequently are candidates for fertility-sparing surgery.[10] The prognosis for most patients with BOTs is excellent, with 5-year survival rate for stage I borderline tumors approximately 95%–97% and for stage II-III patients 65%–87% .[11]

HISTOLOGY

BOTs have been identified in all epithelial subtypes, including endometrioid, clear cell and Brenner (transitional cell), but serous (53.3%) and mucinous histologies (42.5%) are most common.[12] The distribution of the type of BOT shows geographical variation, serous being more common in western countries and mucinous more common in Asian countries. As defined by World Health Organization, histologically BOT exhibits atypical epithelial proliferation with mitotic figures greater than that seen in benign counterparts without destructive stromal invasion. Serous BOT are the most common type which further are of two subtypes, typical serous borderline tumor (90%) and serous borderline tumor with micropapillary pattern(10%).[13] The prognosis of stage 1 typical serous borderline tumors is excellent with 5 year survival of 98%. Even the advanced stage disease with noninvasive peritoneal implants have 5 year survival of 90%, which drops down to 66% in case of invasive implants. Typical serous BOTs are bilateral around 30% of the time. Serous BOTs with micro papillary pattern are more aggressive as suggested by increased incidence of microinvasion, peritoneal invasive impants (50%), surface involvement (50%), lymph node involvement, bilaterality (70%) and advanced stage at diagnosis.[14]

Mucinous variety is second most common type of BOT, which constitutes 10% of all mucinous tumors. They are classified as the intestinal type (85%) and the endocervical type (15%).[15] Intestinal mucinous BOTs occur in relatively older women (40 to 50 years old). They are usually unilateral, large (20-22cm), multilocular cysts, and in most cases are limited to the ovary. Endocervical mucinous BOTs, also referred to as mullerian or seromucinous tumors, occur in younger women (35 to 39 years old). They are relatively smaller (8 to 10 cm) macroscopically unilocular cystic tumors, and are more frequently bilateral (30%) as compared to intestinal variety.. Stage 2 and 3 mucinous BOTs are mostly endocervical type with relatively poor prognosis. With optimum staging and resection, prognosis of intestinal mucinous BOT is excellent in stage I tumor with recurrence rate of 9% in 5 years. Most recurrent cases are due to the possibility of sampling error at the histopathological examination. [15] Adequate pathologic sampling is mandatory to detect a small focus of carcinoma in cases of mucinous BOT as these are heterogeneous, and one tumor can show areas with benign, borderline and malignant features. At least two sections per centimeter are needed, specifically if the tumor is more than 10 cm[16]. Uncommon subtypes of borderline ovarian tumors encompass 3–4% of all BOTs. They include endometrioid, clear cell, transitional (Brenner) borderline tumors, or mixed epithelial tumors.

DIAGNOSIS (Preoperative & Intraoperative)

BOTs till date remains a diagnostic dilemma. They are correctly classified preoperatively only in 29%–69% of cases.[17] BOTs are difficult to classify using subjective evaluation by grayscale and Doppler ultrasound. On the contrary, sonography can accurately distinguish between benign and malignant ovarian tumors preoperatively and guide further operative plan.[17] But because of the overlapping features of BOTs with both benign and malignant tumors, its differentiation becomes difficult. Mucinous intestinal type BOTs are often misclassified as benign mucinous cystadenoma (16%). Micropapillary type of serous BOTs or endocervical type of mucinous BOTs are difficult to differentiate from invasive tumors on ultrasound. In the study by Sokalska et al, 24% (13/55 cases) of borderline tumors were presumed to be invasive ovarian tumors preoperatively.[18] No specific Doppler flow indices are defined currently to diagnose BOTs. The 3D grayscale ultrasound, providing details of the tumor vascular tree patterns, was also not found to be superior to the conventional 2D ultrasound.[19] Investigations based on morphological and vascular tree pattern assessment including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or even positron emission tomography also add very little to the accurate diagnosis of BOTs. One approach which could clinch the diagnosis is by performing both MRI and PET. Ovarian mass that shows complex features suggesting malignancy on MRI but appears benign on PET is strongly likely to be a BOT.[20]

The serum tumor marker CA125 is also of no help. In the systematic review by du Bois et al, of the 1,937 patients with borderline tumors CA125 was negative in 53.8%. [12] In IOTA trial, among 93 patients with BOT, 53% had lower CA125 levels than the cutoff of 35 u/ml. [21] Various indices like RMI (Risk of Malignancy Index) score, based on ultrasound findings and tumor markers are obviously of no diagnostic value. Diagnosis of BOT can be made by histopathology of fresh frozen section sent at the time of surgery but in approximately one third of the cases the diagnosis is revised after final histopathology report of the specimen. Most of the times they are underdiagnosed as benign ovarian tumors than being overdiagnosed.[12] The fresh frozen section is not specific in making the diagnosis of BOT as extensive specimen sampling is required to make the diagnosis.

SEROUS BORDERLINE TUMOR

SEROUS BORDERLINE TUMOR WITH MICROPAPILLARY PATTERN

GROSS SPECIMEN OF SEROUS BOT

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

The staging of the BOTs is done in a similar manner as other ovarian tumours. In order to define the FIGO stages, the entire abdominal cavity must be thoroughly examined; peritoneal washing, hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo oophorectomy, and omentectomy must be performed; and all suspicious lesions must be excised during surgery.

The unresolved issues in management of BOTs are many, including need of lymphadenectomy, justification of fertility sparing surgery, postoperative fertility treatment, laparoscopy as the surgical approach, adjuvant chemotherapy and restaging surgery on incidental diagnosis of BOT.

Routine pelvic and paraaortic lymph node dissection is unnecessary for BOTs except in case of endocervical mucinous BOT. [22]

Fertility-sparing surgery refers to conserving the uterus, with one or both ovaries, during surgical staging. As BOTs are relatively prevalent among young women preserving fertility is often an important issue, which requires a careful approach. The literature available on follow up of these patients, give important source of information regarding the behaviour of BOTs undergoing conservative surgery. Recently published literature describes fertility-sparing surgery as a safe and effective treatment option for BOTs. [21] According to Trillsch et al., the recurrence rate following radical surgery was approximately 5%, whereas that following fertility-sparing surgery was higher at 10% to 20%. The recurrences do not necessarily lower the survival rate as they usually occur in the form of borderline histology. [23] Approximately 50% of BOT patients have natural pregnancies after fertility-sparing surgery. [10, 24] Therefore, this approach should be considered where fertility is desired.

Relapse is common when only cystectomy is done, so oophorectomy should always be the choice unless tumor is bilateral and fertility is desired. In such patients, bilateral oophorectomy with conservation of uterus for subsequent frozen embryo transfer should be considered as another option. And if fertility-sparing surgery with preservation of functioning ovarian parenchyma is performed, extensive sampling of the resection margins of the removed ovarian cyst is very important. [10] Exception to this is mucinous BOT, where complete ovarian cystectomy should always be done, considering high chances of recurrence in malignant form. [25]

LAPAROTOMY VS LAPAROSCOPY

Traditionally, as in malignancy, laparotomy has been the surgical mode of choice for BOT. In recent past, more and more benign ovarian tumors are being operated by laparoscopy and is now considered the standard of care for the same. As it is difficult to diagnose BOTs preoperatively and intraoperatively, they are often underdiagnosed as benign ovarian tumours, only to be identified as BOTs on final histopathology report. Consequently increasing number of cases have been reported with BOT being managed with laparoscopy. This seems to be an attractive approach as it is associated with less postoperative morbidity and peritoneal adhesion formation. The latter may theoretically prove beneficial for preserving fertility.

With new advances in laparoscopic instruments and techniques, staging of BOTs is increasingly being performed laparoscopically. The procedure included are the same as in laparotomy, including tumor debulking (hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy), random and targeted peritoneal biopsies, peritoneal washings, and infracolic omentectomy.

The outcome and feasibility of laparoscopy over laparotomy has been evaluated mainly in retrospective studies. In a retrospective multicentric study by Fauvet et al, 147 patients with BOT were managed laparoscopically. 42 patients required laparoconversion and rest 107 patients were managed with laparoscopy alone. 97.9% of the patients undergoing laparoscopy had stage 1 disease as compared to 88.5% patients undergoing laparotomy. Proportion of conservative surgeries performed was higher in laparoscopy group. Patients were followed for a mean period of 27.5 months. They reported 100% survival and recurrence in 13 patients, which was not significantly different from laparotomy group. More frequent cyst rupture and lower rate of complete surgical staging was seen in laparoscopy. Cyst rupture was usually related to cystectomy. No port site metastasis was reported. They concluded that laparoscopy is an alternative to laparotomy for treatment of BOT, with strict adherence to surgical staging guidelines. [26]

Another retrospective study by Romagnolo et al, included 113 patients with BOTs, of whom 52 were treated by laparoscopy and 61 underwent laparotomy. After the mean follow up for 44 months, no difference was observed in progression free survival between the 2 groups. [27] They also concluded that laparoscopic surgery may be the treatment of choice for BOT.

Later few more studies concluded that if a strict management protocol is followed, minimal access surgery is feasible, safe and can prove to be effective in treatment of BOTs. [28,29] Brosi et al, in the longest documented follow-up (78 months) reported a survival of 100%. [28] However, 17% patient were lost to follow up. The various studies on laparoscopic management of BOTs have been summarized in Table 1. Although no randomized controlled study is available, still it can be concluded from the above data that laparoscopy is safe for BOT if appropriate staging is performed.

LAPAROSCOPY FOR FERTILITY SPARING SURGERY

Conservative surgery for early BOTs is considered safe, though a higher recurrence rate was observed after laparoscopically performed conservative surgery than after a laparotomy (14.9 vs. 7.7%). [12] But this was not confirmed by two multicenter studies, according to which surgical approach (laparoscopy vs laparotomy) did not seem to influence the progression free interval and rate of relapse, rather it depends upon extent of surgical resection. [26,27] Laparoscopy seems to be an attractive approach as it is associated with less postoperative adhesion formation compared with laparotomy, which may theoretically preserve fertility.

Camatte et al [30] presented a series of 34 patient who were intentionally treated with laparoscopy for BOT. 31 among them had fertility sparing conservative surgery. It was concluded that conservative laparoscopic treatment can safely be performed in young patients with early stage BOT. With a median follow-up for 45 months (range 6–228), 6 (17%) patients had recurrence of BOT (none had ovarian malignancy), and two port-site metastases were observed. Spontaneous conception occurred in 6 out of 15 patients desiring pregnancy.

Maneo et al [31] evaluated 62 patients with BOT undergoing fertility sparing surgery, of which 30 were operated laparoscopically, and 32 by laparotomy. Recurrence rate was 37% (11 cases) at a mean follow up of 61 months. They concluded that the diameter of the cyst is a significant factor to predict failure of laparoscopy, with a greater risk of rupture or persistence of the tumour in masses larger than 5 cm.

Tinelli et al [32] studied 43 women with BOT who underwent laparoscopic conservative surgery. At a mean follow up of 44 months, 3 patients (7%) developed recurrences (2 occurred after cystectomy and 1 after oophorectomy). Recurrences did not occur in the cases of intraoperative rupture of cyst. 21 women (49%) became pregnant during the follow-up period.

Seracchioli et al [33] treated 19 women of reproductive age by laparoscopic cystectomy or unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. On a mean follow up of 42 months, 1 patient had a recurrence in the same ovary. This was treated with repeat cystectomy. 6 women became pregnant on follow up.

Romagnolo et al [27] observed relapse rate of 7% for radical and 17% for conservative therapy. They suggested that progression free survival is a function of the extent of sugery performed rather than the mode of surgery.

Zanetta et al [34] noted recurrence rate of 15.2% and 2.5%, respectively, after conservative and radical surgery for stage I disease, and, 40% and 12.9% for stage II disease. They also concluded that conservative approach is reasonable in some cases, and should be followed by definitive surgery after successful pregnancies.

Recurrence rates vary regardless of the surgical approach: salpingo-ophrectomy recurrence rates range from 0% to 10%, cystectomy recurrence rates range from 12% to 58%, and radical surgery recurrence rates range from 2.5% to 5.7% [35, 36].

An important concern in cases managed with conservative surgery is the follow up. No uniform guidelines and recommendations are available. After evaluating physical examination, pelvic ultrasonography, and CA125 levels Zanetta et al [37] concluded that all three modalities together would seem to be the most prudent approach, TVS being the single best investigation for detection of relapse.

All laparoscopic procedures should nevertheless be performed by oncologic surgeons trained in extensive laparoscopic procedures in order to obtain optimal surgical staging, complete debulking, and better results in terms of both relapse free survival and fertility preservation rate [27].

Table 2. Summary of studies of laparoscopically performed surgeries in BOT.

ACCIDENTALLY ENCOUNTERED BOT AFTER LAPAROSCOPY

The incidence of unexpected malignancy encountered after laparoscopy may vary depending on surgeons patients selection for laparoscopy. When done for sonologically benign looking adenexal mass, the rate of unexpected malignancy including BOT, after laparoscopy is expected to be 0–2.5%. [38,39]

A correct preoperative diagnosis of BOT is made only in 30 to 60% of patients, most of them are underdiagnosed as benign ovarian tumor. Shegiko et al [39] repoted 6 cases of BOT among 471 laparoscopically performed surgeries for benign tumors (1.2%). The cases had been followed for minimum of 24 months and maximum of 120 months, with no evidence of relapse. Restaging was not performed in any of the case.

As reported by Matsushita and colleagues [40], among presumably benign 1128 adnexal masses resected laparoscopically, 7 BOTs and 6 malignancies were diagnosed on final histopathology report. In all 13 cases (1.5%) sonology and CA125 were suggestive of benign pathology. They employed fresh frozen section in select cases. Nine patients were upstaged to Stage IC due to intraoperative tumour spillage. After a mean follow up of 38 months, all patients were alive and without recurrence.

RESTAGING

In the study by Shegiko et al, none of the 6 patients with BOT underwent second restaging surgery, with no recurrence reported in follow up period. [40] Matsushita et al, found no malignant tissue after restaging surgery performed in 8 of the 13 patients (61.5%). [40] Hence according to the current evidence, restaging can be avoided in incidentally found early stage BOT. However, these patients should be kept under close follow up.

CONCERNS IN LAPAROSCOPY

Concerns over implementing laparoscopy for BOTs include tumor spillage during surgery, port site metastasis, and chances of incomplete staging, all could potentially results in recurrence. As per the recent FIGO staging, early ovarian tumor (1a and 1b) if gets spilled intraoperatively, the disease is upstaged to 1c. Because of difficult tissue retrieval and dissection techniques in laparoscopy, tumor spillage is common. Nonetheless, the issue of tumor spillage influencing prognosis in early ovarian malignancy is controversial. Even though several recent studied suggests that tumor spillage in early BOT may not affect the prognosis, [41] all care and precaution should be taken to avoid the same. Another concern is the port site metastasis. Port site metastasis after laparoscopic treatment for BOT has been rarely reported. Of the 9 reported cases, surgical excision was performed with a 100% overall survival at 6 to 72 months of follow-up.[42] It is an uncommon complication after laparoscopic surgery for gynecologic malignancies(1-2%) and further rarer for BOT.[26,43]

Figure 1. Suggested management of BOT in various scenarios.

CONCLUSION

BOT is an interesting entity amongst ovarian malignancies, more commonly afflicting relatively young females, showing indolent course and excellent prognosis. Laparoscopic treatment is an attractive alternative to laparotomy which has been proved to be an appropriate and reasonable therapeutic option, especially for early stage BOT. Laparoscopy can be very satisfying for the patient, provided care is taken regarding few things. A systematic evaluation of peritoneum for tumor deposits should be performed, resection of all the deposits should be done, in absence of the same random biopsies are to be taken. Ascitic fluid when present or peritoneal washing for cytology to be collected. The tumor and the peritoneal implants should always be subjected to histopathological examination by fresh frozen sample and close communication with pathologist should be maintained. In case of serous multipapillary BOT, invasive implants, frank malignancy complete resection with lymphadenectomy is required. For tissue retrieval endobag should be used, all efforts should be made to reduce the risk of rupture inside peritoneal cavity and port site metastasis. If the tumor gets ruptured, thorough peritoneal lavage and port site should be cleaned with heparinized saline or povidon iodine. After reviewing the literature, it can very well be concluded that conservative fertility surgery can be performed where desired. Laparoscopy, with careful selection of patients, proves beneficial in fertility preservation as there are less adhesion formation. But taking into account the higher rates of recurrence, patients undergoing fertility sparing surgery must be regularly followed up with clinical examination, transvaginal ultrasound and CA125, for early identification of recurrence. After reviewing the literature it is clear that recurrence is more after cystectomy irrespective of the route, hence it should be reserved only in cases with single involved ovary of bilateral involvement where future childbearing is desired. Also for any stage of BOT no less surgery than bilateral salpingo-ophorectomy should be performed after the age of 40 years. In my opinion when conservative surgery is done second surgery should be planned for completion of the procedure of staging, once the family is completed. Laparoscopic surgery is appropriate option in patients with early stage BOT. Advanced stage, which is rare presentation in BOT can be managed laparoscopically only in expert hands, if adequate staging seems feasible. With advantages over laparotomy like

shorter hospitalizations, lower blood loss, improved visualization, a reduction in need for postoperative analgesics, less morbidity, and more rapid recovery, it should always be considered in managing BOT.

REFERRENCES

1) Sutton GP. Ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. In: Rubin SC, Sutton GP, editors. Ovarian cancer. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. p. 399-417.

2) Querleu D, Leblanc E. Laparoscopic infrarenal para-aortic lymph node dissection for restaging of carcinoma of the ovary or fallopian tube. Cancer 1994;73:1467–71.

3) Tozzi R, Kohler C, Ferrara A, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of early ovarian cancer: surgical and survival outcomes. Gynecologic oncology 2004;93:199-203

4) Lee M, Kim SW, Paek J, et al. Comparisons of surgical outcomes, complications, and costs between laparotomy and laparoscopy in early-stage ovarian cancer. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society 2011;21:251-6.

5) Skirnisdottir I, Garmo H, Wilander E, Holmberg L. Borderline ovarian tumors in Sweden 1960-2005: trends in incidence and age at diagnosis compared to ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer 2008;123:1897-901.

6) Sherman ME, Berman J, Birrer MJ, Cho KR, Ellenson LH, Gorstein F, et al. Current challenges and opportunities for research on borderline ovarian tumors. Hum Pathol 2004;35:961-70

7) Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P et al. Carcinoma of the ovary. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2006;95(suppl 1):S161–S192.

8) Bjorge T, Engeland A, Hansen S et al. Trends in the incidence of ovarian cancer and borderline tumours in Norway, 1954 –1993. Int J Cancer 1997;71:780 –786.

9) van Leeuwen FE, Klip H, Mooij TM et al. Risk of borderline and invasive ovarian tumours after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization in a large Dutch cohort. Hum Reprod 2011;26:3456 –3465.

10) Morice P. Borderline tumours of the ovary and fertility. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:149 –158.

11) Trope C, Davidson B, Paulsen T et al. Diagnosis and treatment of borderline ovarian neoplasms “the state of the art.” Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2009;30:471– 482.

12) du Bois A, Ewald-Riegler N, du Bois O et al. Borderline tumors of the ovary: A systematic review. Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2009;69:807– 833.

13) Lee KR, Tavassoli FA, Prat J et al. Tumours of the ovary and peritoneum. In Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2003:113–202.

14) Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim KR, Kim YT, et al. Micropapillary pattern in serous borderline ovarian tumors: does it matter? Gynecol Oncol 2011;123:511-6.

15) Koskas M, Uzan C, Gouy S, Pautier P, Lhomme C, HaieMeder C, et al. Prognostic factors of a large retrospective series of mucinous borderline tumors of the ovary (excluding peritoneal pseudomyxoma). Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:40-8.

16) Seidman JD, Khedmati F, Yemelyanova AV. Ovarial low grade serous neoplasm: Evaluation of sampling recommendations based on tumors expected to have invasion (those with peritoneal invasive low grade serous carcinoma (invasive implants)). Mod Pathol 2009;22(suppl 1):Abstract 236A.

17) Yazbek J, Ameye L, Timmerman D et al. Use of ultrasound pattern recognition by expert operators to identify borderline ovarian tumors: A study of diagnostic performance and interobserver agreement. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010;35:84–88.

18) Sokalska A, Timmerman D, Testa AC et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound examination for assigning a specific diagnosis to adnexal masses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009;34:462–470.

19) Alcazar JL, Jurado M. Three-dimensional ultrasound for assessing women with gynecological cancer: A systematic review. Gynecol Oncol 2011;120:340–346.

20) Lalwani N, Shanbhogue AK, Vikram R, Nagar A, Jagirdar J, Prasad SR (2010) Current update on borderline ovarian neoplasms. AJR American journal of roentgenology 194: 330–336.

21) Uzan C, Kane A, Rey A, Gouy S, Duvillard P, Morice P. Outcomes after conservative treatment of advanced-stage serous borderline tumors of the ovary. Ann Oncol 2010;21:55-60.

22) Rao GG, Skinner E, Gehrig PA, Duska LR, Coleman RL, Schorge JO. Surgical staging of ovarian low malignant potential tumors. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:261–6.

23) Trillsch F, Mahner S, Ruetzel J, Harter P, Ewald-Riegler N, Jaenicke F, et al. Clinical management of borderline ovarian tumors. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2010;10:1115-24.

24) Tinelli FG, Tinelli R, La Grotta F, Tinelli A, Cicinelli E, Schonauer MM. Pregnancy outcome and recurrence after conservative laparoscopic surgery for borderline ovarian tumors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:81-7.

25) Koskas M, Uzan C, Gouy S et al. Prognostic factors of a large retrospective series of mucinous borderline tumors of the ovary (excluding peritoneal pseudomyxoma). Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:40–48.

26) Fauvet R, Boccara J, Dufournet C et al. Laparoscopic management of borderline ovarian tumors: Results of a French multicenter study. Ann Oncol 2005;16: 403–410.

27) Romagnolo C, Gadducci A, Sartori E et al. Management of borderline ovarian tumors: Results of an Italian multicenter study. Gynecol Oncol 2006;101:255–260.

28) Brosi N, Deckardt R. Endoscopic surgery in patients with borderline tumor of the ovary: a follow-up study of thirty-five patients. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:606–609.

29) Desfeux P, Camatte S, Chatellier G, Blanc B, Querleu D, Lecuru F. Impact of surgical approach on the management of macroscopic early ovarian borderline tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;98:390–395.

30) Camatte S, Morice P, Atallah D, et al. Clinical outcomes after laparoscopic pure management of borderline ovarian tumors: results of a series of 34 patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:605–609.

31) Maneo A, Vignali M, Chiari S, et al. Are borderline tumours of the ovary safely treated by laparoscopy? Gynecologic oncology. 2004;94:387-92.

32) Tinelli FG, Tinelli R, La Grotta F, Tinelli A, Cicinelli E, Schonauer MM. Pregnancy outcome and recurrence after conservative laparoscopic surgery for borderline ovarian tumors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:81-7.

33) Seracchioli R, Venturoli S, Colombo FM, Govoni F, Missiroli S, Bagnoli A. Fertility and tumor recurrence rate after conservative laparoscopic management of young women with early-stage borderline ovarian tumors. Fertil Steril 2001;76:999–1004.07;86:81–7.

34) Zanetta G, Rota S, Chiari S, Bonazzi C, Bratina G, Mangioni C. Behavior of borderline tumors with particular interest to persistence, recurrence, and progression to invasive carcinoma: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:2658–64.

35) Cadron I, Leunen K, Van Gorp T, Amant F, Neven P, Vergote I. Management of borderline ovarian neoplasms. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25: 2928–2937.

36) Boran N, Cil AP, Tulunay G, Ozturkoglu E, Koc S, Bulbul D, et al. Fertility and recurrence results of conservative surgery for borderline ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:845–51.

37) Zanetta G, Rota S, Lissoni A. Ultrasound, physical examination, and CA125 measurement for the detection of recurrence after conservative surgery for early borderline ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol 2001;81: 63–6.

38) MuziiL, AngioliR, ZulloM, PaniciPB. The unexpected ovarian malignany found during operative laparoscopy: incidence, management, and implications for prognosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2005;12:81–89; quiz 90–81.

39) Saito S, kajiyama H, Miwa Y, Mizuno M, Kikkawa F, Tanaka S, Okomoto T.Unexpected ovarian malignancy found after laparoscopic surgery in patients with adnexal masses–a single institutional experience. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014; 76: 83-90.

40) Matsushita H, Watanabe K, Yokoi T, Wakatsuki A. Unexpected ovarian malignancy following laparoscopic excision of adenexal masses. Human Reproduction. 2014; 29(9): 1912-7.

41) Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Suzuki S, Ino K, Nawa A, Kawai M, Nagasaka T, Kikkawa F (2010) Fertilitysparing surgery in young women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. European journal of surgical oncology: the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology 36: 404–408.

42) Morice P, Camatte S, Larregain-Fournier D, Thoury A, Duvillard P, Castaigne D. Port-site implantation after laparoscopic treatment of borderline ovarian tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1167–1170.

43) Ramirez PT, Wolf JK, Levenback C. Laparoscopic port-site metastases: etiology and prevention. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:179–89