Page 48 - WJOLS

P. 48

Medhat M Ibrahim et al

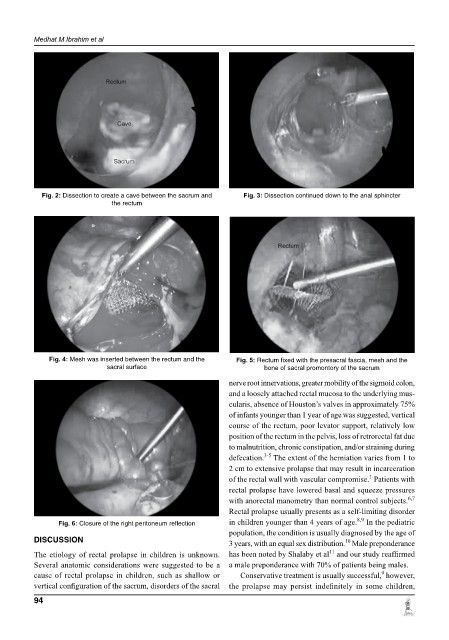

Fig. 2: Dissection to create a cave between the sacrum and Fig. 3: Dissection continued down to the anal sphincter

the rectum

Fig. 4: Mesh was inserted between the rectum and the Fig. 5: Rectum fixed with the presacral fascia, mesh and the

sacral surface bone of sacral promontory of the sacrum

nerve root innervations, greater mobility of the sigmoid colon,

and a loosely attached rectal mucosa to the underlying mus-

cularis, absence of Houston’s valves in approximately 75%

of infants younger than 1 year of age was suggested, vertical

course of the rectum, poor levator support, relatively low

position of the rectum in the pelvis, loss of retrorectal fat due

to malnutrition, chronic constipation, and/or straining during

3-5

defecation. The extent of the herniation varies from 1 to

2 cm to extensive prolapse that may result in incarceration

1

of the rectal wall with vascular compromise. Patients with

rectal prolapse have lowered basal and squeeze pressures

6,7

with anorectal manometry than normal control subjects.

Rectal prolapse usually presents as a self-limiting disorder

8,9

Fig. 6: Closure of the right peritoneum reflection in children younger than 4 years of age. In the pediatric

population, the condition is usually diagnosed by the age of

diSCUSSion 3 years, with an equal sex distribution. Male preponderance

10

11

The etiology of rectal prolapse in children is unknown. has been noted by Shalaby et al and our study reaffirmed

Several anatomic considerations were suggested to be a a male preponderance with 70% of patients being males.

9

cause of rectal prolapse in children, such as shallow or Conservative treatment is usually successful, however,

vertical configuration of the sacrum, disorders of the sacral the prolapse may persist indefinitely in some children,

94