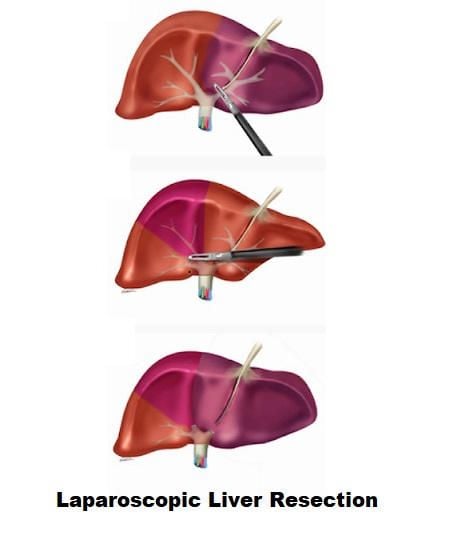

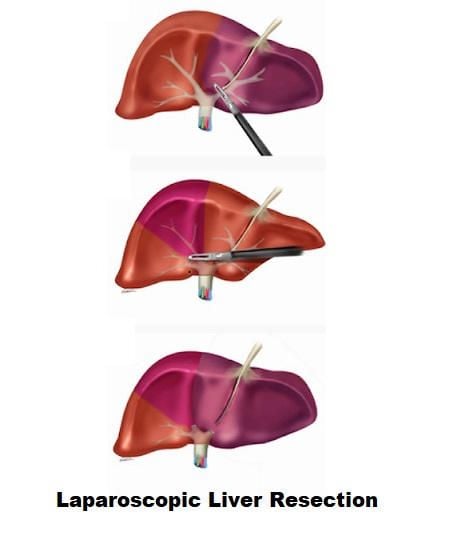

Laparoscopic Technique of Liver Resection

The most common indication for laparoscopic liver resection is a solitary liver metastasis from colorectal cancer, but it may also be used for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and for benign liver tumors or cysts.

Laparoscopic liver resections offer advantages over the conventional open approach in two important respects:

1. Reduced operative blood loss

2. Lower major postoperative morbidity.

Although laparoscopic staging for intra-abdominal cancer including primary and secondary hepatic tumors has been in established practice for many years, laparoscopic liver resections are still in the early clinical evaluation stage. Nonetheless, the results to date have been uniformly favorable especially for left lobectomy and pluri-segmentectomies although right hepatectomy has been performed by the laparoscopically assisted or the hand-assisted laparoscopic surgical (HALS) approach.

The HALS approach by facilitating these dissections and greatly increasing the safety makes quite a big difference to the uptake amongst hepatobiliary and general surgeons with an interest in liver surgery. The procedures, which are in established practice by the laparoscopic and HALS approach are:

1. Extended laparoscopic staging

2. Hepatic resections

3. Laparoscopic in situ thermal ablation

4. Laparoscopic cryosurgery

5. Radical de-roofing of simple hepatic cysts

6. Hepatic surgery for parasitic cysts.

Laparoscopic Staging of Tumors

Laparoscopy can nicely detect seedling metastases and small hepatic deposits missed by preoperative thin slice multidetector CT or MRI. Some surgeons add lavage cytology to diagnostic laparoscopic visual inspection. This detects exfoliated tumors cells in gastrointestinal, pancreatic, and ovarian cancers.

Hepatic Resections

Approaches

Both the laparoscopic and the HALS approach can be used for hepatic resection. The hand-assisted approach expedites the operation and provides an effective safeguard against major hemorrhage that may be encountered during the operation. A 7.0 cm incision is necessary for the insertion of the hand access device, such as the Omni port. This may be introduced through midline for operations on the left lobe or right transverse for resections on the right liver. It is important that the optical port is placed such that it is well clear of the internal hand.

Component Tasks in Laparoscopic Hepatic Resections

These component tasks cover all the surgical technical aspects of the various hepatic resections: hepatectomy, pluri-segmentectomies, segmentectomies.

Contact Ultrasound Localization and Mapping of the Intended Resection

Contact ultrasound is indispensable for hepatic resections. The precise localization and extent of the lesion especially when this is intrahepatic can only be determined by contact ultrasound scanning, the findings of which determine the extent of resection segments required. In contrast, the mapping of the outlines of the resection is best carried out by the argon plasma spray coagulation.

Division of Falciform Ligament

The division of falciform ligament is needed for major right and left resections. The division of the falciform ligament close to the liver substance is best carried out with a combination of scissors and electrocoagulation and is greatly facilitated by the use of curved coaxial instruments. The round ligament ligamentum teres can be left undivided except in patients undergoing skeletonization for right extended hepatectomy.

Exposure of Suprahepatic Inferior Vena Cava and Main Hepatic Veins

Exposure of suprahepatic inferior vena cava and main hepatic veins are only required for major hepatectomies. The two leaves of the falciform ligament separate posteriorly to envelop the suprahepatic inferior vena cava and the three main hepatic veins. The right leaf becomes the upper leaf of the right coronary ligament of the liver and the left becomes the upper layer of the left triangular ligament. Both leaves are divided after soft coagulation with the curved coaxial scissors. Ultrasonic shears may be used for this purpose, but this is more difficult as this energized device is straight.

The peritoneal division is extended in both directions to open up the retrohepatic caval space, which consists of relatively avascular loose fibroareolar tissue. The upper end of the caval canal is dissected further with a combination of blunt and sharp scissor dissection to divide fibrous bands. As the dissection precedes, about 1.5 cm of the inferior vena cava, the origin of the right hepatic vein is exposed. Further exposure of the right and middle hepatic veins is achieved beneath the liver and from the right side required for a right hepatectomy. The left hepatic vein is very easily exposed from the left side above the liver.

Exposure of Infrahepatic Inferior Vena Cava and Division of the Posterior Minor Hepatic Veins

Exposure of intrahepatic inferior vena cava and division of the posterior minor hepatic vein is necessary for the skeletonization of the right liver necessary for a right hepatectomy. It is performed by retraction of the inferior surface of the right lobe of the liver with an atraumatic flexible ring or fan retractor to put the peritoneum sweeping up from the right kidney to the liver on the stretch. This peritoneum is divided with the curved coaxial scissors and soft electrocoagulation over a wide front and close to the liver edge. There is usually little fat found underneath the peritoneum except in very obese individuals.

Once the peritoneum is divided the retractor is replaced which gently lifts the inferoposterior aspect of the liver upwards to expose the areolar tissue plane covering the vena cava and the minor retrohepatic veins which vary in number from 3 to 5. The infero-posterior aspect of the liver is lifted gently but progressively to expose the vena cava behind the liver. As minor hepatic veins are encountered draining into the inferior vena cava, they are skeletonized by the curved coaxial scissors and then clipped before they are divided. The mobilization continues upwards until the right and the middle hepatic vein is reached.

Opening the Cave of Retius

Opening the cave of Retius is common to both right and left resections. The cave of Retius refers to the umbilical fissure bridged by a variable amount of hepatic tissue anteriorly, which overlies the ligamentum teres containing the obliterated umbilical vein on its way to join the left branch of the portal vein at the bottom of the pit. The bridge of liver tissue is crushed and coagulated by an insulated grasping forceps, after which it is divided which will separate segment III on the left side from the quadrate lobe opening up the cave of Retius and exposing the terminal segment of the round ligament.

Hilar Dissection

The dissection of the hilum commences by a division of the peritoneum along the margin of the hepatic hilum to expose the common hepatic duct and its bifurcation and the right and left branches of the common hepatic artery. Further dissection is needed to bring down the hilar plate and to skeletonize the right and left hepatic ducts, the two branches of the common hepatic artery, and, more posteriorly, the two branches of the portal vein for right and left hepatectomy.

Removal of the Gallbladder

Removal of the gallbladder en bloc with the hepatic substance constitutes an integral part of right hepatectomy and segmentectomy involving segments IVa and V. The dissection of the cystic duct and artery is followed by ligature or clipping of the medial end of the cystic duct and clipping of its lateral end before it is divided.

Inflow Occlusion Prior to Hepatic Resection

Temporary inflow occlusion of the vascular supply to the liver is necessary for major hepatic resections and also to reduce the ‘heat-sink effect’ of the substantial blood flow through the liver during in situ ablation by cryotherapy or radiofrequency thermal ablation. Several types of clamps are available for this purpose but the most suitable are the parallel occlusion clamps, which are introduced through 5.5 mm ports by means of an applicator, which is used to engage and disengage the clamps. Thus, when the clamp is in use it does not occupy a port, which can thus be used for dissection. The application of these parallel occlusion clamps is very easy particularly with the hand-assisted approach and minimal dissection is required. The surgeon just makes a small window through an avascular area of lesser omentum just proximal to the hepatoduodenal ligament enveloping the bile duct, hepatic arteries, and portal vein.

The parallel occlusion clamp is introduced from the right by means of its applicator. The jaws are opened as the hepatoduodenal ligament is reached and applied across the full width of the hepatoduodenal ligament and then released to occlude the bile duct, portal vein, and hepatic arteries. It is extremely important that the period of inflow vascular occlusion to the liver does not exceed 30 minutes at any one-time period. For removal of the clamp, the introducer is inserted through the port and used to engage the clamp, which then is opened and removed through the same port by the introducer.

Transection of the Hepatic Parenchyma

The transection of the hepatic parenchyma for all the major resections should be carried in the absence of a positive- pressure pneumoperitoneum. In hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery, this translates to replacement of the hand access device with a disposable retractor that also acts as a wound protector preventing its contamination by malignant cells during the hepatic resection and removal of the specimen. The hepatic resection must also be carried out with a low patient CVP, produced by a head-up tilt and appropriate vasodilator medication by the anesthetist. The hepatic artery to the resection area is best secured by clips or ligatures in the liver substance rather than extrahepatically. The vascular stapling or ligature and division of the main hepatic veins draining the liver during hepatectomy are carried out at the end of the parenchymal transection. The actual technique of liver resection varies from a simple finger or forceps fracture with individual clipping or ligature of bile ductules to the use of energized systems like ultrasonic dissection or LigaSure. The liver parenchymal surface is first coagulated and then crushed using a long-jawed crushing laparoscopic forceps to fracture the liver parenchyma exposing sizeable vessels and ducts. All sizeable blood vessels and bile ducts are clipped before being cut. As the cleft deepens, bands of liver tissue, which are not severed, are presumed to contain large vessels that may be obscured by adherent layer of liver parenchyma. In this situation, palpation of the bridge between the index finger and thumb of the assisting hand will identify the nature of the structure.

All sizeable veins can be transected using an endolinear cutting stapler mounted with 35 mm vascular cartridge introduced through the minilaparotomy wound.

In the case of pluri-segmentectomy, after the segment has been separated on three sides, it often remains attached to the liver by a bridge of liver tissue. If this connection is no thicker than 1.0 cm, it is simply staple transected by the application of the endolinear cutting stapler to detach completely the area from the liver. After resection, the specimen is removed through the open minilaparotomy wound. The final stage consists of securing complete hemostasis.

Hemostasis of the Cut Liver Surface

Only minor oozing happens from the cut liver substance if the technique of hepatic transaction has been performed correctly and in the presence of a low CVP of a patient. Complete hemostasis is achieved by argon plasma coagulation. The application of fibrin glue or other synthetic sealants is very helpful in preventing hemostasis.

Insertion of Drains

Once the resection is complete before the retractor is removed and the wound closed using mass closure with monofilament polydioxanone the silicon drain should be introduced. It is advisable to insert two large silicon drains one above and the other below the liver. These must be sutured to the abdominal wall to prevent accidental dislodgment after the operation. Effective drainage is crucial to prevent postoperative biloma.

Postoperative Management

It is important to stress that these patients should be nursed postoperatively in a hepatobiliary unit with immediate access to high dependency and intensive care if needed. The management is the same as after any other laparoscopic surgery with daily monitoring of the liver function tests, hematology, and blood urea nitrogen and serum electrolytes. Opiate medication and sedation are avoided in patients with compromised liver function. A repeated ultrasound scan should be carried out in all patients after hepatic resection. This is necessary to identify early fluid collections most usually bile, which if found are monitored by serial ultrasound studies and aspirated or drained percutaneously under radiological control if persistent. Using the right technique, necessary expertise, and appropriate technology, laparoscopic and especially hand-assisted hepatic resections can be carried out safely. The data from the published reports to date indicate benefits over the open approach and these include reduced blood loss and lower postoperative morbidity.

The most common indication for laparoscopic liver resection is a solitary liver metastasis from colorectal cancer, but it may also be used for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and for benign liver tumors or cysts.

Laparoscopic liver resections offer advantages over the conventional open approach in two important respects:

1. Reduced operative blood loss

2. Lower major postoperative morbidity.

Although laparoscopic staging for intra-abdominal cancer including primary and secondary hepatic tumors has been in established practice for many years, laparoscopic liver resections are still in the early clinical evaluation stage. Nonetheless, the results to date have been uniformly favorable especially for left lobectomy and pluri-segmentectomies although right hepatectomy has been performed by the laparoscopically assisted or the hand-assisted laparoscopic surgical (HALS) approach.

The HALS approach by facilitating these dissections and greatly increasing the safety makes quite a big difference to the uptake amongst hepatobiliary and general surgeons with an interest in liver surgery. The procedures, which are in established practice by the laparoscopic and HALS approach are:

1. Extended laparoscopic staging

2. Hepatic resections

3. Laparoscopic in situ thermal ablation

4. Laparoscopic cryosurgery

5. Radical de-roofing of simple hepatic cysts

6. Hepatic surgery for parasitic cysts.

Laparoscopic Staging of Tumors

Laparoscopy can nicely detect seedling metastases and small hepatic deposits missed by preoperative thin slice multidetector CT or MRI. Some surgeons add lavage cytology to diagnostic laparoscopic visual inspection. This detects exfoliated tumors cells in gastrointestinal, pancreatic, and ovarian cancers.

Hepatic Resections

Approaches

Both the laparoscopic and the HALS approach can be used for hepatic resection. The hand-assisted approach expedites the operation and provides an effective safeguard against major hemorrhage that may be encountered during the operation. A 7.0 cm incision is necessary for the insertion of the hand access device, such as the Omni port. This may be introduced through midline for operations on the left lobe or right transverse for resections on the right liver. It is important that the optical port is placed such that it is well clear of the internal hand.

Component Tasks in Laparoscopic Hepatic Resections

These component tasks cover all the surgical technical aspects of the various hepatic resections: hepatectomy, pluri-segmentectomies, segmentectomies.

Contact Ultrasound Localization and Mapping of the Intended Resection

Contact ultrasound is indispensable for hepatic resections. The precise localization and extent of the lesion especially when this is intrahepatic can only be determined by contact ultrasound scanning, the findings of which determine the extent of resection segments required. In contrast, the mapping of the outlines of the resection is best carried out by the argon plasma spray coagulation.

Division of Falciform Ligament

The division of falciform ligament is needed for major right and left resections. The division of the falciform ligament close to the liver substance is best carried out with a combination of scissors and electrocoagulation and is greatly facilitated by the use of curved coaxial instruments. The round ligament ligamentum teres can be left undivided except in patients undergoing skeletonization for right extended hepatectomy.

Exposure of Suprahepatic Inferior Vena Cava and Main Hepatic Veins

Exposure of suprahepatic inferior vena cava and main hepatic veins are only required for major hepatectomies. The two leaves of the falciform ligament separate posteriorly to envelop the suprahepatic inferior vena cava and the three main hepatic veins. The right leaf becomes the upper leaf of the right coronary ligament of the liver and the left becomes the upper layer of the left triangular ligament. Both leaves are divided after soft coagulation with the curved coaxial scissors. Ultrasonic shears may be used for this purpose, but this is more difficult as this energized device is straight.

The peritoneal division is extended in both directions to open up the retrohepatic caval space, which consists of relatively avascular loose fibroareolar tissue. The upper end of the caval canal is dissected further with a combination of blunt and sharp scissor dissection to divide fibrous bands. As the dissection precedes, about 1.5 cm of the inferior vena cava, the origin of the right hepatic vein is exposed. Further exposure of the right and middle hepatic veins is achieved beneath the liver and from the right side required for a right hepatectomy. The left hepatic vein is very easily exposed from the left side above the liver.

Exposure of Infrahepatic Inferior Vena Cava and Division of the Posterior Minor Hepatic Veins

Exposure of intrahepatic inferior vena cava and division of the posterior minor hepatic vein is necessary for the skeletonization of the right liver necessary for a right hepatectomy. It is performed by retraction of the inferior surface of the right lobe of the liver with an atraumatic flexible ring or fan retractor to put the peritoneum sweeping up from the right kidney to the liver on the stretch. This peritoneum is divided with the curved coaxial scissors and soft electrocoagulation over a wide front and close to the liver edge. There is usually little fat found underneath the peritoneum except in very obese individuals.

Once the peritoneum is divided the retractor is replaced which gently lifts the inferoposterior aspect of the liver upwards to expose the areolar tissue plane covering the vena cava and the minor retrohepatic veins which vary in number from 3 to 5. The infero-posterior aspect of the liver is lifted gently but progressively to expose the vena cava behind the liver. As minor hepatic veins are encountered draining into the inferior vena cava, they are skeletonized by the curved coaxial scissors and then clipped before they are divided. The mobilization continues upwards until the right and the middle hepatic vein is reached.

Opening the Cave of Retius

Opening the cave of Retius is common to both right and left resections. The cave of Retius refers to the umbilical fissure bridged by a variable amount of hepatic tissue anteriorly, which overlies the ligamentum teres containing the obliterated umbilical vein on its way to join the left branch of the portal vein at the bottom of the pit. The bridge of liver tissue is crushed and coagulated by an insulated grasping forceps, after which it is divided which will separate segment III on the left side from the quadrate lobe opening up the cave of Retius and exposing the terminal segment of the round ligament.

Hilar Dissection

The dissection of the hilum commences by a division of the peritoneum along the margin of the hepatic hilum to expose the common hepatic duct and its bifurcation and the right and left branches of the common hepatic artery. Further dissection is needed to bring down the hilar plate and to skeletonize the right and left hepatic ducts, the two branches of the common hepatic artery, and, more posteriorly, the two branches of the portal vein for right and left hepatectomy.

Removal of the Gallbladder

Removal of the gallbladder en bloc with the hepatic substance constitutes an integral part of right hepatectomy and segmentectomy involving segments IVa and V. The dissection of the cystic duct and artery is followed by ligature or clipping of the medial end of the cystic duct and clipping of its lateral end before it is divided.

Inflow Occlusion Prior to Hepatic Resection

Temporary inflow occlusion of the vascular supply to the liver is necessary for major hepatic resections and also to reduce the ‘heat-sink effect’ of the substantial blood flow through the liver during in situ ablation by cryotherapy or radiofrequency thermal ablation. Several types of clamps are available for this purpose but the most suitable are the parallel occlusion clamps, which are introduced through 5.5 mm ports by means of an applicator, which is used to engage and disengage the clamps. Thus, when the clamp is in use it does not occupy a port, which can thus be used for dissection. The application of these parallel occlusion clamps is very easy particularly with the hand-assisted approach and minimal dissection is required. The surgeon just makes a small window through an avascular area of lesser omentum just proximal to the hepatoduodenal ligament enveloping the bile duct, hepatic arteries, and portal vein.

The parallel occlusion clamp is introduced from the right by means of its applicator. The jaws are opened as the hepatoduodenal ligament is reached and applied across the full width of the hepatoduodenal ligament and then released to occlude the bile duct, portal vein, and hepatic arteries. It is extremely important that the period of inflow vascular occlusion to the liver does not exceed 30 minutes at any one-time period. For removal of the clamp, the introducer is inserted through the port and used to engage the clamp, which then is opened and removed through the same port by the introducer.

Transection of the Hepatic Parenchyma

The transection of the hepatic parenchyma for all the major resections should be carried in the absence of a positive- pressure pneumoperitoneum. In hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery, this translates to replacement of the hand access device with a disposable retractor that also acts as a wound protector preventing its contamination by malignant cells during the hepatic resection and removal of the specimen. The hepatic resection must also be carried out with a low patient CVP, produced by a head-up tilt and appropriate vasodilator medication by the anesthetist. The hepatic artery to the resection area is best secured by clips or ligatures in the liver substance rather than extrahepatically. The vascular stapling or ligature and division of the main hepatic veins draining the liver during hepatectomy are carried out at the end of the parenchymal transection. The actual technique of liver resection varies from a simple finger or forceps fracture with individual clipping or ligature of bile ductules to the use of energized systems like ultrasonic dissection or LigaSure. The liver parenchymal surface is first coagulated and then crushed using a long-jawed crushing laparoscopic forceps to fracture the liver parenchyma exposing sizeable vessels and ducts. All sizeable blood vessels and bile ducts are clipped before being cut. As the cleft deepens, bands of liver tissue, which are not severed, are presumed to contain large vessels that may be obscured by adherent layer of liver parenchyma. In this situation, palpation of the bridge between the index finger and thumb of the assisting hand will identify the nature of the structure.

All sizeable veins can be transected using an endolinear cutting stapler mounted with 35 mm vascular cartridge introduced through the minilaparotomy wound.

In the case of pluri-segmentectomy, after the segment has been separated on three sides, it often remains attached to the liver by a bridge of liver tissue. If this connection is no thicker than 1.0 cm, it is simply staple transected by the application of the endolinear cutting stapler to detach completely the area from the liver. After resection, the specimen is removed through the open minilaparotomy wound. The final stage consists of securing complete hemostasis.

Hemostasis of the Cut Liver Surface

Only minor oozing happens from the cut liver substance if the technique of hepatic transaction has been performed correctly and in the presence of a low CVP of a patient. Complete hemostasis is achieved by argon plasma coagulation. The application of fibrin glue or other synthetic sealants is very helpful in preventing hemostasis.

Insertion of Drains

Once the resection is complete before the retractor is removed and the wound closed using mass closure with monofilament polydioxanone the silicon drain should be introduced. It is advisable to insert two large silicon drains one above and the other below the liver. These must be sutured to the abdominal wall to prevent accidental dislodgment after the operation. Effective drainage is crucial to prevent postoperative biloma.

Postoperative Management

It is important to stress that these patients should be nursed postoperatively in a hepatobiliary unit with immediate access to high dependency and intensive care if needed. The management is the same as after any other laparoscopic surgery with daily monitoring of the liver function tests, hematology, and blood urea nitrogen and serum electrolytes. Opiate medication and sedation are avoided in patients with compromised liver function. A repeated ultrasound scan should be carried out in all patients after hepatic resection. This is necessary to identify early fluid collections most usually bile, which if found are monitored by serial ultrasound studies and aspirated or drained percutaneously under radiological control if persistent. Using the right technique, necessary expertise, and appropriate technology, laparoscopic and especially hand-assisted hepatic resections can be carried out safely. The data from the published reports to date indicate benefits over the open approach and these include reduced blood loss and lower postoperative morbidity.