Laparoscopic Repair of Duodenal Perforation

Introduction

Perforation is a life-threatening complication of peptic ulcer disease. Duodenal perforation is a common complication of duodenal ulcers. The first clinical description of perforated duodenal perforation was made by Crisp in 1843. Laparoscopic treatment of perforated duodenum was first reported by Mouret in 1989. Perforated duodenal ulcer is mainly a disease of young men but because of increasing smoking in women and the use of NSAID in all the age groups, nowadays, it is common in all adult populations. In western society, it is a problem seen mainly in elderly women due to smoking, alcohol, and the use of NSAIDs. Increased incidence in the elderly is possibly due to increased NSAID use. The majority of patients of perforated duodenal ulcers are H. pylori-positive.

Diagnosis is made clinically and confirmed by the presence of pneumoperitoneum on radiographs. Non-operative management is successful in patients identified to have a spontaneously sealed perforation proven by water-soluble contrast gastroduodenogram. For most of the patients of perforation of duodenal ulcers, the preferred treatment is its immediate surgical repair. The traditional management of perforated duodenal ulcer was Graham Patch Plication described in 1937. Laparoscopic repair of duodenal perforation by Graham Patch Plication is an excellent alternative approach. Operative management consists of the time-honored practice of omental patch closure, but now this can be done by laparoscopic methods. The practice of the addition of acid-reducing procedures is currently being debated though it continues to be recommended in high-risk patients. Laparoscopic approaches to the closure of duodenal perforation are now being applied widely and may become the gold standard in the future especially in patients with < 10 mm perforation size presenting within the first 24 hours of the onset of pain. The role of Helicobacter pylori in duodenal ulcer perforation is controversial and more studies are needed to answer this question though recent indirect evidence suggests that eradicating H. pylori may reduce the necessity for adding acid-reducing procedures and the associated morbidity.

Perforated duodenal ulcer is a surgical emergency. Laparoscopic repair of duodenal perforation is a useful method for reducing hospital stay, complications, and return to normal activity. In many elegantly designed and meticulously executed prospective randomized trial, the laparoscopic approach in the management of perforated peptic ulcer disease has been compared to the open approach. Studies validate that a laparoscopic approach is safe, feasible, and with morbidity and mortality comparable to that of the open approach. With better training in minimal access surgery now available, the time has arrived for it to take its place in the surgeon’s repertoire.

Laparoscopic approach has the following advantages:

• Cosmetically better outcome

• Less tissue dissection and disruption of tissue planes

• Less pain postoperatively

• Low intraoperatively and postoperative complications

• Early return to work.

The main tasks of this operation consist of:

• Preparation of the patient

• Creation of pneumoperitoneum

• Insertion of port

• Diagnostic laparoscopy and locating the perforation

• Cleaning the abdomen

• Closure of the perforation with an omental patch

• Irrigation and suction of operating field

• Final diagnostic laparoscopy for any bowel injury or hemorrhage

• Removal of the instrument with the complete exit of CO2

• Closure of wound.

Patient Selection

Duodenal perforation is a laparoscopic emergency. If the patient's condition is otherwise fit and peritonitis is diagnosed within 12 hours of onset it is possible to repair the perforation by laparoscopic method. After 12 hours chemical peritonitis will give way to bacterial peritonitis, with severe sepsis, and then the laparoscopic repair is not advisable.

Operative Technique

Patient Position

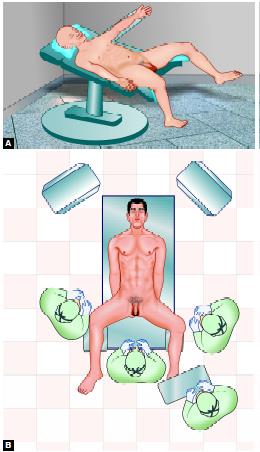

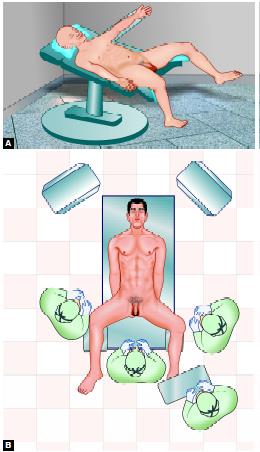

The patient is placed on the operating table with the legs in stirrups, the knees slightly bent and the hips flexed approximately 10°. The operating table is tilted head up by approximately 15°. A compression bandage is used on the leg during the operation to prevent thromboembolism. The surgeon stands between the patient's legs. The first assistant, whose main task is to position the video camera, sits on the patient’s left side. The instrument trolley is placed on the patient's left allowing the scrub nurse to assist with placing the appropriate instruments in the operating ports. Television monitors are positioned on either side of the top end of the operating table at a suitable height for a surgeon, anesthetist, and assistant to see the procedure.

Position of the patient for laparoscopic repair of duodenal perforation

Anesthesia

General endotracheal anesthesia is used. Each patient is injected in the pre-induction phase with 60 mg IM contramol, IV metronidazole or tinidazole and with 2 g of cefizox IV. The H2 receptor antagonist like ranitidine injection is also advisable.

Creation of Pneumoperitoneum

• Check Veress needle before insertion

• Check Veress needle tip spring

• Confirm that gas connection is functioning

• Ensure flushing with saline (does not block that needle)

• Make a small incision just above the umbilicus

• Lift up an abdominal wall and gently insert Veress needle till a feeling of giving way and two click sound

• Confirm the position of the needle by saline drop tests

• Connect CO2 tube to needle and confirm Quadro-manometric indicators

• Switch off gas when the desired pneumoperitoneum is created and remove the Veress needle.

Port Location

Four ports are then inserted, using the triangulation concept, to form a diamond-shape. The surgeon usually stands between the legs of the patient. A 10 mm camera port is placed in the umbilicus; this position will vary according to the build of the patient. A 5 mm port is inserted in the right upper quadrant 8 to 10 cm from the midline. A 5 mm port is placed in the left upper quadrant and another 5 mm port is placed in the right subxiphoid region. The patient is placed in reverse Trendelenburg’s position, with the first assistant to the right and a second assistant to the left. The surgeon thus works comfortably with two hands, triangulated with the cameras.

Port position for laparoscopic repair of duodenal perforation

Locating the Perforation

The gallbladder, which usually adheres to the perforation, is retracted by the surgeon’s left hand and moved upwards. The gallbladder is passed to the assistant using the subxiphoid port which is placed to the right of the falciform ligament. The exposed area is checked and the perforation is usually clearly identified as a pinpoint hole on the anterior aspect of the duodenum.

Cleaning the Abdomen

The whole abdomen should be irrigated and aspirated with about 10 liters of saline mixed with antibiotics. Each quadrant is cleaned methodically, starting at the right upper quadrant, going to the left, moving down to the left lower quadrant, and then finally over to the right. Special attention should be given to the vesicorectal pouch. Fibrous membranes are removed as much as possible since they might contain bacteria.

Closure of the Perforation with an Omental Patch

A flappy piece of omentum flap should be taken and the assistant holds the omentum patch just over the perforation using both the hands. Intracorporeal knot together with an omental patch should be applied to seal the perforation. The perforation is closed by intracorporeal stitches (simple closure by 3/0 vicryl on SKI needle) and re-enforced by a pedicle omental graft. This was followed by a complete lavage of the peritoneal cavity with an ample amount of warm physiological saline. Always insert the omental patch in the knot rather than the tail of the knot to hold the omentum because, with the latter, a small space remains between the knots. Do not use extracorporeal knotting because this exerts tension on the friable tissue.

Closure of perforation with omental patch

Ending of the Operation

At the end of the procedure, the abdomen should be examined for any possible bowel injury or hemorrhage. The instruments and then the ports should be removed. The telescope should be removed leaving the gas valve of umbilical port open to let out all the gas. Closure of the wound is done with suture, vicryl for rectus, and unabsorbable intradermal or stapler for the skin. Adhesive sterile dressing over the wound should be applied. A patient may be discharged 2 days. Oral intake was started after 48 hours, starting with clear fluids. They all received the triple therapy regimen, which consisted of Clarithromycin and Amoxicillin for 10 days, in addition to Omeprazole for 14 days. This was followed by gastroduodenoscopy after 2 months. All patients were followed on an outpatient basis for 6 months and 40 (66%) of them for up to 2 years.

Discussion

The incidence of perforated duodenal perforation remains the same. Operative treatment of perforated duodenal ulcer consists of the time-honored practice of omental patch closure but now this can be done by laparoscopic method. Laparoscopic approaches to the closure of duodenal perforation are now being applied widely and may become the gold standard in the future especially in a patient with < 10 mm perforation size presented within the first 24 hours of the onset of pain. Perforated duodenal ulcer is a surgical emergency. Urgent simple closure of the perforation with omental patching is widely applied for the vast number of these patients, the general consensus is to perform simple closure alone without definite procedures especially patients with poor surgical risks and severe peritonitis. Various laparoscopic techniques have been advocated for closing the perforation intra-and extracorporeal knots, sutureless techniques, holding the omental patch by fibrin glue, or sealing with a gelatin sponge, stapled patch closure, or gastroscopically aided management in the perforation. Many surgeons have reported patients with sealed perforation by peritoneal lavage and drainage only.

Laparoscopic Closure of Perforation Offers Important Advantages

• Decreased postoperative pain

• Less abdominal wall complication

• Better visualization and ability to carry out a thorough peritoneal lavage

• Cosmetically better outcome

• Lower intraoperative and postoperative complications

• Early return to work

• Early mobilization

• Lower mortality

• It is as safe and effective as open surgery

• Patients subjective well being was better after laparoscopic repair of perforated DU.

Laparoscopic duodenal ulcer perforation closure was performed in thirty patients. The interval before surgical intervention from the onset of perforation ranged between 20 and 36 hours. Perforation closure with Graham’s patch omentoplasty was performed in all cases. In three patients, posterior truncal vagotomy and anterior highly selective vagotomy was combined with perforation closure. The oral fluid was permitted in the second POD in 21 patients and others on the third and fourth postoperative day. Postoperative morbidity was very minimal. Two patients had a trocar site infection. All the patients were discharged between 5th and 7th postoperative day.

Though the management of peptic ulceration has reduced the incidence of perforated peptic ulcer, it remains a challenging disease for the surgeons since it is an emergency procedure. The proper management of this complication of peptic ulcer disease has generated a lot of discussions, laparoscopic surgical treatment of perforated peptic ulcer is an attractive alternative for conventional treatment because of the absence of complications as compared to conventional surgery for patients who develop perforation in the setting of H. pylori infection. Eradication of infection may prevent ulcer recurrence.

Those patients who tolerate insult and whose ulcer was sealed may be adopted for non-operative therapy. However, the decision of non-operative therapy is difficult and can be done only after evaluation by and close consultation with an experienced surgeon. If non-operative treatment is chosen, then the patient requires frequent clinical examinations so the operative therapy can be done at the first sign of clinical deterioration. A variety of laparoscopic techniques have been described. A combined laparoscopic- endoscopic method described, also mini-laparoscopy was described. Intracorporeal suturing was better than extracorporeal knotting because the latter one is liable to cut. The choice between combining definitive treatment and simple closure is still a matter of controversy. The choice depends on certain factors including age, fitness, and status of the peritoneal cavity. The definitive surgical procedure of choice in perforated duodenal ulcer is patch closure and highly selective vagotomy. Although this procedure has low mortality and morbidity it is technically demanding and requires an experienced surgeon to ensure adequate vagotomy.

In this series, 30 cases of perforated duodenal perforation, three were treated with combined definitive treatment. Older patients with septic shock and generalized peritonitis should better be served by conventional surgery. Open conversion may be required especially in the presence of certain high-risk factors as:

• Inadequate ulcer localization

• Posterior location of gastric ulcer

• Pancreatic infiltration (penetrating ulcer)

• Localized abscess formation.

It has been shown that the age, presence of concomitant disease and length of free air or fluid collection in abdominal CT scan correlate with conversion in a meta-analysis of 13 publication comprising 658 patients comparing open versus laparoscopic closure of perforated duodenal perforation, it was found that postoperative pain was lower after laparoscopic repair than open repair supported by a significant reduction in postoperative analgesic requirement after laparoscopy repair meta-analysis demonstrated a significant reduction in wound infection after laparoscopic repair as compared with open. But, a significant higher re-operation rate was observed after laparoscopic perforated duodenal repair. Laparoscopic perforated duodenal repair is a safe and reliable procedure associated with short operating time, less postoperative pain, reduced chest complication, shorter postoperative hospital stay, and earlier returns to normal daily activity than conventional open repair. Operative time is also shorter and morbidity also lowers, in laparoscopic repair of perforated duodenal perforation. Also, low mortality, a better cosmetic outcome with laparoscopic repair, postoperative adhesions, and incision hernia were lower in comparison with the open method. Laparoscopic repair is as safe and effective as open repair. The patient’s subjective well- being was better after laparoscopic repair. Laparoscopy provides a better vision of the peritoneal cavity and allows early mobilization. The incidence of perforated peptic ulcer disease has decreased nowadays with a vast improvement in medical therapy. However, minimally invasive surgery still has a significant role to play in the treatment of complicated diseases. It decreases hospital stay and overall recovery period as compared to open surgery regardless of the preference of the individual surgeon. Our result has shown that the laparoscopic surgery may become the gold standard for surgical treatment of complicated peptic ulcer disease.

Laparoscopic closure of duodenal ulcer perforation is an attractive alternative to conventional surgery with the benefits of minimally invasive surgery such as parietal wall integrity, cosmetic benefits, and early subjective postoperative comfort and rehabilitation.

Introduction

Perforation is a life-threatening complication of peptic ulcer disease. Duodenal perforation is a common complication of duodenal ulcers. The first clinical description of perforated duodenal perforation was made by Crisp in 1843. Laparoscopic treatment of perforated duodenum was first reported by Mouret in 1989. Perforated duodenal ulcer is mainly a disease of young men but because of increasing smoking in women and the use of NSAID in all the age groups, nowadays, it is common in all adult populations. In western society, it is a problem seen mainly in elderly women due to smoking, alcohol, and the use of NSAIDs. Increased incidence in the elderly is possibly due to increased NSAID use. The majority of patients of perforated duodenal ulcers are H. pylori-positive.

Diagnosis is made clinically and confirmed by the presence of pneumoperitoneum on radiographs. Non-operative management is successful in patients identified to have a spontaneously sealed perforation proven by water-soluble contrast gastroduodenogram. For most of the patients of perforation of duodenal ulcers, the preferred treatment is its immediate surgical repair. The traditional management of perforated duodenal ulcer was Graham Patch Plication described in 1937. Laparoscopic repair of duodenal perforation by Graham Patch Plication is an excellent alternative approach. Operative management consists of the time-honored practice of omental patch closure, but now this can be done by laparoscopic methods. The practice of the addition of acid-reducing procedures is currently being debated though it continues to be recommended in high-risk patients. Laparoscopic approaches to the closure of duodenal perforation are now being applied widely and may become the gold standard in the future especially in patients with < 10 mm perforation size presenting within the first 24 hours of the onset of pain. The role of Helicobacter pylori in duodenal ulcer perforation is controversial and more studies are needed to answer this question though recent indirect evidence suggests that eradicating H. pylori may reduce the necessity for adding acid-reducing procedures and the associated morbidity.

Perforated duodenal ulcer is a surgical emergency. Laparoscopic repair of duodenal perforation is a useful method for reducing hospital stay, complications, and return to normal activity. In many elegantly designed and meticulously executed prospective randomized trial, the laparoscopic approach in the management of perforated peptic ulcer disease has been compared to the open approach. Studies validate that a laparoscopic approach is safe, feasible, and with morbidity and mortality comparable to that of the open approach. With better training in minimal access surgery now available, the time has arrived for it to take its place in the surgeon’s repertoire.

Laparoscopic approach has the following advantages:

• Cosmetically better outcome

• Less tissue dissection and disruption of tissue planes

• Less pain postoperatively

• Low intraoperatively and postoperative complications

• Early return to work.

The main tasks of this operation consist of:

• Preparation of the patient

• Creation of pneumoperitoneum

• Insertion of port

• Diagnostic laparoscopy and locating the perforation

• Cleaning the abdomen

• Closure of the perforation with an omental patch

• Irrigation and suction of operating field

• Final diagnostic laparoscopy for any bowel injury or hemorrhage

• Removal of the instrument with the complete exit of CO2

• Closure of wound.

Patient Selection

Duodenal perforation is a laparoscopic emergency. If the patient's condition is otherwise fit and peritonitis is diagnosed within 12 hours of onset it is possible to repair the perforation by laparoscopic method. After 12 hours chemical peritonitis will give way to bacterial peritonitis, with severe sepsis, and then the laparoscopic repair is not advisable.

Operative Technique

Patient Position

The patient is placed on the operating table with the legs in stirrups, the knees slightly bent and the hips flexed approximately 10°. The operating table is tilted head up by approximately 15°. A compression bandage is used on the leg during the operation to prevent thromboembolism. The surgeon stands between the patient's legs. The first assistant, whose main task is to position the video camera, sits on the patient’s left side. The instrument trolley is placed on the patient's left allowing the scrub nurse to assist with placing the appropriate instruments in the operating ports. Television monitors are positioned on either side of the top end of the operating table at a suitable height for a surgeon, anesthetist, and assistant to see the procedure.

Position of the patient for laparoscopic repair of duodenal perforation

Anesthesia

General endotracheal anesthesia is used. Each patient is injected in the pre-induction phase with 60 mg IM contramol, IV metronidazole or tinidazole and with 2 g of cefizox IV. The H2 receptor antagonist like ranitidine injection is also advisable.

Creation of Pneumoperitoneum

• Check Veress needle before insertion

• Check Veress needle tip spring

• Confirm that gas connection is functioning

• Ensure flushing with saline (does not block that needle)

• Make a small incision just above the umbilicus

• Lift up an abdominal wall and gently insert Veress needle till a feeling of giving way and two click sound

• Confirm the position of the needle by saline drop tests

• Connect CO2 tube to needle and confirm Quadro-manometric indicators

• Switch off gas when the desired pneumoperitoneum is created and remove the Veress needle.

Port Location

Four ports are then inserted, using the triangulation concept, to form a diamond-shape. The surgeon usually stands between the legs of the patient. A 10 mm camera port is placed in the umbilicus; this position will vary according to the build of the patient. A 5 mm port is inserted in the right upper quadrant 8 to 10 cm from the midline. A 5 mm port is placed in the left upper quadrant and another 5 mm port is placed in the right subxiphoid region. The patient is placed in reverse Trendelenburg’s position, with the first assistant to the right and a second assistant to the left. The surgeon thus works comfortably with two hands, triangulated with the cameras.

Port position for laparoscopic repair of duodenal perforation

Locating the Perforation

The gallbladder, which usually adheres to the perforation, is retracted by the surgeon’s left hand and moved upwards. The gallbladder is passed to the assistant using the subxiphoid port which is placed to the right of the falciform ligament. The exposed area is checked and the perforation is usually clearly identified as a pinpoint hole on the anterior aspect of the duodenum.

Cleaning the Abdomen

The whole abdomen should be irrigated and aspirated with about 10 liters of saline mixed with antibiotics. Each quadrant is cleaned methodically, starting at the right upper quadrant, going to the left, moving down to the left lower quadrant, and then finally over to the right. Special attention should be given to the vesicorectal pouch. Fibrous membranes are removed as much as possible since they might contain bacteria.

Closure of the Perforation with an Omental Patch

A flappy piece of omentum flap should be taken and the assistant holds the omentum patch just over the perforation using both the hands. Intracorporeal knot together with an omental patch should be applied to seal the perforation. The perforation is closed by intracorporeal stitches (simple closure by 3/0 vicryl on SKI needle) and re-enforced by a pedicle omental graft. This was followed by a complete lavage of the peritoneal cavity with an ample amount of warm physiological saline. Always insert the omental patch in the knot rather than the tail of the knot to hold the omentum because, with the latter, a small space remains between the knots. Do not use extracorporeal knotting because this exerts tension on the friable tissue.

Closure of perforation with omental patch

Ending of the Operation

At the end of the procedure, the abdomen should be examined for any possible bowel injury or hemorrhage. The instruments and then the ports should be removed. The telescope should be removed leaving the gas valve of umbilical port open to let out all the gas. Closure of the wound is done with suture, vicryl for rectus, and unabsorbable intradermal or stapler for the skin. Adhesive sterile dressing over the wound should be applied. A patient may be discharged 2 days. Oral intake was started after 48 hours, starting with clear fluids. They all received the triple therapy regimen, which consisted of Clarithromycin and Amoxicillin for 10 days, in addition to Omeprazole for 14 days. This was followed by gastroduodenoscopy after 2 months. All patients were followed on an outpatient basis for 6 months and 40 (66%) of them for up to 2 years.

Discussion

The incidence of perforated duodenal perforation remains the same. Operative treatment of perforated duodenal ulcer consists of the time-honored practice of omental patch closure but now this can be done by laparoscopic method. Laparoscopic approaches to the closure of duodenal perforation are now being applied widely and may become the gold standard in the future especially in a patient with < 10 mm perforation size presented within the first 24 hours of the onset of pain. Perforated duodenal ulcer is a surgical emergency. Urgent simple closure of the perforation with omental patching is widely applied for the vast number of these patients, the general consensus is to perform simple closure alone without definite procedures especially patients with poor surgical risks and severe peritonitis. Various laparoscopic techniques have been advocated for closing the perforation intra-and extracorporeal knots, sutureless techniques, holding the omental patch by fibrin glue, or sealing with a gelatin sponge, stapled patch closure, or gastroscopically aided management in the perforation. Many surgeons have reported patients with sealed perforation by peritoneal lavage and drainage only.

Laparoscopic Closure of Perforation Offers Important Advantages

• Decreased postoperative pain

• Less abdominal wall complication

• Better visualization and ability to carry out a thorough peritoneal lavage

• Cosmetically better outcome

• Lower intraoperative and postoperative complications

• Early return to work

• Early mobilization

• Lower mortality

• It is as safe and effective as open surgery

• Patients subjective well being was better after laparoscopic repair of perforated DU.

Laparoscopic duodenal ulcer perforation closure was performed in thirty patients. The interval before surgical intervention from the onset of perforation ranged between 20 and 36 hours. Perforation closure with Graham’s patch omentoplasty was performed in all cases. In three patients, posterior truncal vagotomy and anterior highly selective vagotomy was combined with perforation closure. The oral fluid was permitted in the second POD in 21 patients and others on the third and fourth postoperative day. Postoperative morbidity was very minimal. Two patients had a trocar site infection. All the patients were discharged between 5th and 7th postoperative day.

Though the management of peptic ulceration has reduced the incidence of perforated peptic ulcer, it remains a challenging disease for the surgeons since it is an emergency procedure. The proper management of this complication of peptic ulcer disease has generated a lot of discussions, laparoscopic surgical treatment of perforated peptic ulcer is an attractive alternative for conventional treatment because of the absence of complications as compared to conventional surgery for patients who develop perforation in the setting of H. pylori infection. Eradication of infection may prevent ulcer recurrence.

Those patients who tolerate insult and whose ulcer was sealed may be adopted for non-operative therapy. However, the decision of non-operative therapy is difficult and can be done only after evaluation by and close consultation with an experienced surgeon. If non-operative treatment is chosen, then the patient requires frequent clinical examinations so the operative therapy can be done at the first sign of clinical deterioration. A variety of laparoscopic techniques have been described. A combined laparoscopic- endoscopic method described, also mini-laparoscopy was described. Intracorporeal suturing was better than extracorporeal knotting because the latter one is liable to cut. The choice between combining definitive treatment and simple closure is still a matter of controversy. The choice depends on certain factors including age, fitness, and status of the peritoneal cavity. The definitive surgical procedure of choice in perforated duodenal ulcer is patch closure and highly selective vagotomy. Although this procedure has low mortality and morbidity it is technically demanding and requires an experienced surgeon to ensure adequate vagotomy.

In this series, 30 cases of perforated duodenal perforation, three were treated with combined definitive treatment. Older patients with septic shock and generalized peritonitis should better be served by conventional surgery. Open conversion may be required especially in the presence of certain high-risk factors as:

• Inadequate ulcer localization

• Posterior location of gastric ulcer

• Pancreatic infiltration (penetrating ulcer)

• Localized abscess formation.

It has been shown that the age, presence of concomitant disease and length of free air or fluid collection in abdominal CT scan correlate with conversion in a meta-analysis of 13 publication comprising 658 patients comparing open versus laparoscopic closure of perforated duodenal perforation, it was found that postoperative pain was lower after laparoscopic repair than open repair supported by a significant reduction in postoperative analgesic requirement after laparoscopy repair meta-analysis demonstrated a significant reduction in wound infection after laparoscopic repair as compared with open. But, a significant higher re-operation rate was observed after laparoscopic perforated duodenal repair. Laparoscopic perforated duodenal repair is a safe and reliable procedure associated with short operating time, less postoperative pain, reduced chest complication, shorter postoperative hospital stay, and earlier returns to normal daily activity than conventional open repair. Operative time is also shorter and morbidity also lowers, in laparoscopic repair of perforated duodenal perforation. Also, low mortality, a better cosmetic outcome with laparoscopic repair, postoperative adhesions, and incision hernia were lower in comparison with the open method. Laparoscopic repair is as safe and effective as open repair. The patient’s subjective well- being was better after laparoscopic repair. Laparoscopy provides a better vision of the peritoneal cavity and allows early mobilization. The incidence of perforated peptic ulcer disease has decreased nowadays with a vast improvement in medical therapy. However, minimally invasive surgery still has a significant role to play in the treatment of complicated diseases. It decreases hospital stay and overall recovery period as compared to open surgery regardless of the preference of the individual surgeon. Our result has shown that the laparoscopic surgery may become the gold standard for surgical treatment of complicated peptic ulcer disease.

Laparoscopic closure of duodenal ulcer perforation is an attractive alternative to conventional surgery with the benefits of minimally invasive surgery such as parietal wall integrity, cosmetic benefits, and early subjective postoperative comfort and rehabilitation.