Laparoscopic Management of Endometriosis

Introduction

Endometriosis is a progressive, often debilitating disease, affecting 10 to 15 percent of women during their reproductive years. Among gynecologic disorders, endometriosis is surpassed in frequency only by leiomyomas. Laparoscopy and the surgical laser allowed definitive treatment following diagnosis. The debate continues as to whether laparotomy or operative laparoscopy is more effective for the treatment of endometriosis. In women with bowel symptoms such as dyschezia, tenesmus, or cyclic rectal bleeding without any other pathology, a sigmoidoscopic examination should be done at the time of menstruation to rule out bowel involvement of endometrial implant. However, many women do not demonstrate rectal lesions, but at the time of laparoscopy, significant bowel involvement is seen. It should be remembered that a negative sigmoidoscopy does not rule out bowel involvement in patients of endometriosis. In patients who have significant rectovaginal nodularity on physical examination, preoperative bowel preparation is necessary and antibiotics are administered the day of surgery. Gynecologists should also consult with a general surgeon experienced in laparoscopic bowel resections. A preoperative ultrasound can assess the ovaries for endometriomas. Preoperative hormonal suppressive therapy can be useful in decreasing the inflammation, bleeding, and possible postoperative adhesion formation.

The goals of surgery are to remove all implants, resects adhesion, relieve pain, and reduce the risk of recurrence and to prevent postoperative adhesion formation. It should also restore involved organs normal anatomical and physiological conditions. In the case of infertility restoration of tubo-ovarian relationship is essential to restore fertility. Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the definitive treatment of endometriosis. In advanced disease, the ovary may have adhered to the pelvic sidewall. Ovarian dissection may increase the risk of injury to the ureter and vessels in the triangle of doom. The retroperitoneal approach is helpful in these cases and ensures complete removal of ovarian tissue. It also avoids ovarian remnant syndrome.

Bilateral oophorectomy must be performed to eliminate the estrogen that sustains and stimulate the ectopic endometrium. Following hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy patient often require hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Administering the minimal effective dose of estrogen is sometimes associated with a small risk of recurrence. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) should begin postoperatively. Patients with residual disease may benefit from receiving progesterone from 2 to 6 months followed by combined progesterone and estrogen for an additional 9 months. Conservative surgery is indicated for women who desire pregnancy and whose disease is responsible for the symptom of pain and infertility. Surgery improves the likelihood of pregnancy and offers pain relief. Twenty-five percent of patients undergoing conservative operation may require a subsequent operation. The rate of surgery directly depends on the extent of disease. Those who achieve pregnancy after surgery, only 10 percent require another operation. Conservative operations are cytoreductive and recurrence of symptom most likely is caused by the progression of existing pathology that was missed during laparoscopy.

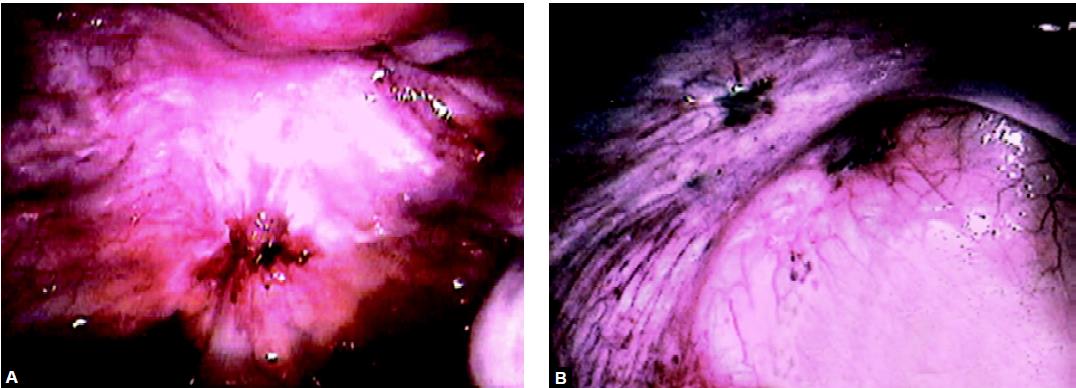

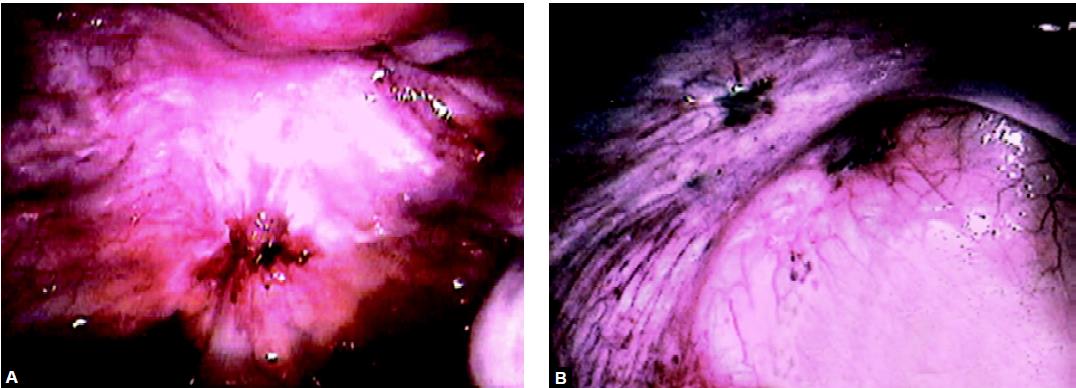

Complete removal of endometriosis is difficult because of there variability in appearance and visibility. Powder burn lesions represent foci of inactive disease containing stroma and gland embedded in hemosiderin deposit. These lesions are more common in older lesions and sometimes without any symptoms. When endometriosis involves uterosacral ligament, they are palpable as a tender nodule and may cause dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia. Superficial endometriosis is treated optimally by electrosurgical fulguration or ablation. If large areas of the peritoneum are involved with endometriosis or if a woman has recurrent endometriosis in an area previously ablated by electrosurgery or laser, it may be better to excise that entire area of the peritoneum to prevent a recurrence. Especially, areas with scarring or fibrosis should be excised carefully because there may be endometriosis beneath them. One concern in laser ablation or excising large areas of the peritoneum is the chance of adhesion formation. Animal studies indicate that these areas are reperitonealized in 24 to 48 hours by the migration of surrounding peritoneum and that adhesion formation is low after laparoscopy. However, the surgeon should be cautious particularly when excising areas of peritoneum which are opposed by pelvic organs.

Sometimes atypical lesions are seen as a clear vesicle, pink vascular pattern, white scarred lesion, red lesion, yellow-brown patches, and peritoneal windows, which represent active endometriosis. These lesions secrete prostaglandin into the peritoneal fluid. The depth of endometrial implants may be related to the level of disease activity and symptoms. The peritoneum must be examined from all the angles and from different degrees of illumination to see all types of lesions. The peritoneal folds must be stretched and search for small and atypical lesions. Normal appearing ovaries sometime may contain endometriosis under the apparently normal cortex. By inserting the needle in the ovary small endometriosis can be identified by seeing the color of aspirated content.

Endometriosis

All the pelvic organs are inspected thoroughly. In 15 percent of cases, the appendix is involved and so it should be examined. The endometriosis which has penetrated retroperitoneally, several centimeters is called an iceberg lesion. It can be detected laparoscopically by palpating areas of the pelvis and bowel with the suction irrigation probe. With the forceps or probe, the endometriotic implant is examined and their size, depth, and proximity to a normal pelvic structure are evaluated. The diagnostic laparoscopy may turn into operative one if the surgeon has consented. The operative procedure begins by removing adhesions if present between the bowel and pelvic organs to adequately expose the pelvic cavity. The ovaries and tube may be adhered with the cul-de-sac or pelvic sidewall. These organs are freed from adhesions and chromotubated. Endometrial implants and endometriomas are resected or vaporized, and if the patient has significant central pelvic pain, uterosacral nerve ablation or presacral nerve resection is performed.

Lysis of Bowel Adhesions

Tubo-ovarian mass with bowel adhesion is a common finding in extensive endometriosis. Bowel adhesions vary in thickness, vascularity, and cohesiveness. Some adhesions are stretched without tearing the tissue and should be excised with electrosurgery at the points of attachment to the pelvic organs. Dense adhesions are excised either with scissors or the ultrasonic dissector. The adhered structures requiring separation are pulled apart with forcers and a cleavage plane is formed. Hydrodissection is useful to identify and develop the dissection plane, which is ablated or excised, using dissecting scissors.

Peritoneal Implants

At the time of treating peritoneal endometriosis, the implants should be destroyed in the most effective and least traumatic manner to minimize postoperative adhesions and injury to retroperitoneal vessels and nerves. Although different modalities have been used, hydro dissection and high- power fulguration or CO2 laser are the best choices for endometriosis treatment. Superficial peritoneal endometriosis may be vaporized with monopolar or bipolar current or excised. Implants less than 2 mm are coagulated, vaporized, or excised. As lesions exceed 3 mm, vaporization or excision is needed. For lesions greater than 5 mm, deep vaporization or excisional techniques are required. If vaporization is chosen, it is important to copiously irrigate and remove the charred areas to confirm the complete removal of the lesion and to avoid confusing endometriosis with a carbon deposit.

Resection of Ovarian Endometriosis

The ovaries are a common site for endometriosis. Endometrial implants or endometriomas less than 2 cm in diameter are coagulated; laser ablated or excised using scissors, biopsy forceps, or electrodes. For successful eradication, all visible lesions and scars must be removed from the ovarian surface. Entrapment of oocytes within the luteinized ovarian follicle, as reported in experimental animal models, must be avoided. Endometriomas more than 2 cm diameter must be resected thoroughly to prevent a recurrence. Draining the endometriomas or partial resection of its wall is inadequate because the endometrial tissue lining the cyst is likely to remain functional and can cause the symptoms to recur. Many gynecologists like to perform ovarian cystoscopy and biopsy of the cyst wall before ablating the cyst. By using a double optic laparoscope, which involves the passage of a smaller operative endoscope through the channel of the main laparoscope, the ovarian cyst may be punctured, drained, the fluid sent for cytology, and the lining of the inner cystic wall is visually inspected. Once it confirmed that the cyst is not malignant, its wall is ablated to a depth of 3 to 4 mm.

Chocolate cyst

Endometrioma, deroofing, and marsupialization

For endometriomas over 2 cm in diameter, the cyst is punctured with aspiration needle and aspirated with the suction-irrigator probe. Deroofing of the cyst wall is performed. The cyst wall should be removed by grasping its base with laparoscopic forceps and peeling it from the ovarian stroma. If the peeling of the remaining wall is not possible it should be ablated using electrosurgical fulguration. When the entire cyst wall is ablated, representative biopsies are taken for histological diagnosis.

Cyst wall closure is not necessary, according to animal experiments for large defects that result from resecting endometriomas larger than 5 cm; the edges of the ovarian cortex are approximated with a single suture placed within the ovarian stroma. Fibrin sealant has been described to atraumatically approximate the edges of large ovarian defects, without adhesion formation.

Although rare, some patients present with localized symptoms and severe involvement of only one ovary with disease and adhesions while the opposite ovary is normal. These patients are benefited by unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. By removing the diseased ovary, the risk of disease recurrence is minimized, and the fertility potential is improved by limiting ovulation to the healthy side.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a progressive, often debilitating disease, affecting 10 to 15 percent of women during their reproductive years. Among gynecologic disorders, endometriosis is surpassed in frequency only by leiomyomas. Laparoscopy and the surgical laser allowed definitive treatment following diagnosis. The debate continues as to whether laparotomy or operative laparoscopy is more effective for the treatment of endometriosis. In women with bowel symptoms such as dyschezia, tenesmus, or cyclic rectal bleeding without any other pathology, a sigmoidoscopic examination should be done at the time of menstruation to rule out bowel involvement of endometrial implant. However, many women do not demonstrate rectal lesions, but at the time of laparoscopy, significant bowel involvement is seen. It should be remembered that a negative sigmoidoscopy does not rule out bowel involvement in patients of endometriosis. In patients who have significant rectovaginal nodularity on physical examination, preoperative bowel preparation is necessary and antibiotics are administered the day of surgery. Gynecologists should also consult with a general surgeon experienced in laparoscopic bowel resections. A preoperative ultrasound can assess the ovaries for endometriomas. Preoperative hormonal suppressive therapy can be useful in decreasing the inflammation, bleeding, and possible postoperative adhesion formation.

The goals of surgery are to remove all implants, resects adhesion, relieve pain, and reduce the risk of recurrence and to prevent postoperative adhesion formation. It should also restore involved organs normal anatomical and physiological conditions. In the case of infertility restoration of tubo-ovarian relationship is essential to restore fertility. Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the definitive treatment of endometriosis. In advanced disease, the ovary may have adhered to the pelvic sidewall. Ovarian dissection may increase the risk of injury to the ureter and vessels in the triangle of doom. The retroperitoneal approach is helpful in these cases and ensures complete removal of ovarian tissue. It also avoids ovarian remnant syndrome.

Bilateral oophorectomy must be performed to eliminate the estrogen that sustains and stimulate the ectopic endometrium. Following hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy patient often require hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Administering the minimal effective dose of estrogen is sometimes associated with a small risk of recurrence. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) should begin postoperatively. Patients with residual disease may benefit from receiving progesterone from 2 to 6 months followed by combined progesterone and estrogen for an additional 9 months. Conservative surgery is indicated for women who desire pregnancy and whose disease is responsible for the symptom of pain and infertility. Surgery improves the likelihood of pregnancy and offers pain relief. Twenty-five percent of patients undergoing conservative operation may require a subsequent operation. The rate of surgery directly depends on the extent of disease. Those who achieve pregnancy after surgery, only 10 percent require another operation. Conservative operations are cytoreductive and recurrence of symptom most likely is caused by the progression of existing pathology that was missed during laparoscopy.

Complete removal of endometriosis is difficult because of there variability in appearance and visibility. Powder burn lesions represent foci of inactive disease containing stroma and gland embedded in hemosiderin deposit. These lesions are more common in older lesions and sometimes without any symptoms. When endometriosis involves uterosacral ligament, they are palpable as a tender nodule and may cause dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia. Superficial endometriosis is treated optimally by electrosurgical fulguration or ablation. If large areas of the peritoneum are involved with endometriosis or if a woman has recurrent endometriosis in an area previously ablated by electrosurgery or laser, it may be better to excise that entire area of the peritoneum to prevent a recurrence. Especially, areas with scarring or fibrosis should be excised carefully because there may be endometriosis beneath them. One concern in laser ablation or excising large areas of the peritoneum is the chance of adhesion formation. Animal studies indicate that these areas are reperitonealized in 24 to 48 hours by the migration of surrounding peritoneum and that adhesion formation is low after laparoscopy. However, the surgeon should be cautious particularly when excising areas of peritoneum which are opposed by pelvic organs.

Sometimes atypical lesions are seen as a clear vesicle, pink vascular pattern, white scarred lesion, red lesion, yellow-brown patches, and peritoneal windows, which represent active endometriosis. These lesions secrete prostaglandin into the peritoneal fluid. The depth of endometrial implants may be related to the level of disease activity and symptoms. The peritoneum must be examined from all the angles and from different degrees of illumination to see all types of lesions. The peritoneal folds must be stretched and search for small and atypical lesions. Normal appearing ovaries sometime may contain endometriosis under the apparently normal cortex. By inserting the needle in the ovary small endometriosis can be identified by seeing the color of aspirated content.

Endometriosis

All the pelvic organs are inspected thoroughly. In 15 percent of cases, the appendix is involved and so it should be examined. The endometriosis which has penetrated retroperitoneally, several centimeters is called an iceberg lesion. It can be detected laparoscopically by palpating areas of the pelvis and bowel with the suction irrigation probe. With the forceps or probe, the endometriotic implant is examined and their size, depth, and proximity to a normal pelvic structure are evaluated. The diagnostic laparoscopy may turn into operative one if the surgeon has consented. The operative procedure begins by removing adhesions if present between the bowel and pelvic organs to adequately expose the pelvic cavity. The ovaries and tube may be adhered with the cul-de-sac or pelvic sidewall. These organs are freed from adhesions and chromotubated. Endometrial implants and endometriomas are resected or vaporized, and if the patient has significant central pelvic pain, uterosacral nerve ablation or presacral nerve resection is performed.

Lysis of Bowel Adhesions

Tubo-ovarian mass with bowel adhesion is a common finding in extensive endometriosis. Bowel adhesions vary in thickness, vascularity, and cohesiveness. Some adhesions are stretched without tearing the tissue and should be excised with electrosurgery at the points of attachment to the pelvic organs. Dense adhesions are excised either with scissors or the ultrasonic dissector. The adhered structures requiring separation are pulled apart with forcers and a cleavage plane is formed. Hydrodissection is useful to identify and develop the dissection plane, which is ablated or excised, using dissecting scissors.

Peritoneal Implants

At the time of treating peritoneal endometriosis, the implants should be destroyed in the most effective and least traumatic manner to minimize postoperative adhesions and injury to retroperitoneal vessels and nerves. Although different modalities have been used, hydro dissection and high- power fulguration or CO2 laser are the best choices for endometriosis treatment. Superficial peritoneal endometriosis may be vaporized with monopolar or bipolar current or excised. Implants less than 2 mm are coagulated, vaporized, or excised. As lesions exceed 3 mm, vaporization or excision is needed. For lesions greater than 5 mm, deep vaporization or excisional techniques are required. If vaporization is chosen, it is important to copiously irrigate and remove the charred areas to confirm the complete removal of the lesion and to avoid confusing endometriosis with a carbon deposit.

Resection of Ovarian Endometriosis

The ovaries are a common site for endometriosis. Endometrial implants or endometriomas less than 2 cm in diameter are coagulated; laser ablated or excised using scissors, biopsy forceps, or electrodes. For successful eradication, all visible lesions and scars must be removed from the ovarian surface. Entrapment of oocytes within the luteinized ovarian follicle, as reported in experimental animal models, must be avoided. Endometriomas more than 2 cm diameter must be resected thoroughly to prevent a recurrence. Draining the endometriomas or partial resection of its wall is inadequate because the endometrial tissue lining the cyst is likely to remain functional and can cause the symptoms to recur. Many gynecologists like to perform ovarian cystoscopy and biopsy of the cyst wall before ablating the cyst. By using a double optic laparoscope, which involves the passage of a smaller operative endoscope through the channel of the main laparoscope, the ovarian cyst may be punctured, drained, the fluid sent for cytology, and the lining of the inner cystic wall is visually inspected. Once it confirmed that the cyst is not malignant, its wall is ablated to a depth of 3 to 4 mm.

Chocolate cyst

Endometrioma, deroofing, and marsupialization

For endometriomas over 2 cm in diameter, the cyst is punctured with aspiration needle and aspirated with the suction-irrigator probe. Deroofing of the cyst wall is performed. The cyst wall should be removed by grasping its base with laparoscopic forceps and peeling it from the ovarian stroma. If the peeling of the remaining wall is not possible it should be ablated using electrosurgical fulguration. When the entire cyst wall is ablated, representative biopsies are taken for histological diagnosis.

Cyst wall closure is not necessary, according to animal experiments for large defects that result from resecting endometriomas larger than 5 cm; the edges of the ovarian cortex are approximated with a single suture placed within the ovarian stroma. Fibrin sealant has been described to atraumatically approximate the edges of large ovarian defects, without adhesion formation.

Although rare, some patients present with localized symptoms and severe involvement of only one ovary with disease and adhesions while the opposite ovary is normal. These patients are benefited by unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. By removing the diseased ovary, the risk of disease recurrence is minimized, and the fertility potential is improved by limiting ovulation to the healthy side.