Laparoscopic Fundoplication

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as the failure of the antireflux barrier, allowing abnormal reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. It is a mechanical disorder that is caused by a defective lower esophageal sphincter, a gastric emptying disorder, or failed esophageal peristalsis. Gastroesophageal reflux is one of the most common digestive symptoms. Exposure of the esophageal mucosa to acid, enzymes and other digestive secretions, leads to acute and chronic inflammation, with pain, and ulceration or stricture formation if untreated.

Heartburn occurs in 5 to 45 percent of adults in western countries, depending on the frequency of symptoms 30 to 45 percent suffer from symptoms once a month and 5 to 10 percent every day. The majority of patients suffering from GERD experience minor symptoms for which they do not seek medical attention. Age does not seem to have an impact on the frequency of GERD symptoms, and no causal factor has been identified. Esophagitis due to reflux occurs in approximately 2 percent of the global population. It is the most frequent form of lesion detected on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, occurring more frequently than gastric ulcers or duodenal ulcers. GERD is often a chronic ailment. After a 5 to 10 years follow-up, about two-thirds of patients complain of persistent symptoms requiring occasional or continuous treatment.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GERD is multifactorial, although it is usually due to the weakening of the anatomical or functional gastroesophageal barrier located at the esophagogastric junction. Injury to the esophageal mucosa by acid-peptic gastric secretions, while secondary to this weakening, plays a major role in the development of GERD symptoms and lesions. In fact, suppressing the gastric acid secretion, which is the usual treatment of this ailment, leads to the disappearance of symptoms and healing of lesions in almost all cases. GERD is, therefore acid dependent.

Symptoms

• Heartburn (Retrosternal burning)

• Regurgitation

• Pain

• Respiratory symptoms.

Diagnostic Test

• Endoscopy

• Barium swallow

• Esophageal transit + /- manometry

• pH monitoring.

Treatment of GERD

Medical therapy is the first line of management. Esophagitis will heal in approximately 90 percent of cases with intensive medical therapy. However, symptoms recur in more than 80 percent of cases within one year of drug withdrawal. Since it is a chronic condition, medical therapy involving acid suppression and/or promotility agents may be required for the rest of a patient’s life. Despite the fact that current medical management is very effective for the majority, a small number of patients do not get complete relief of symptoms. Currently, there is increasing interest in the surgical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

The goal of surgical therapy is to recreate an antireflux barrier. It is the only treatment capable of changing the natural history of GERD. There has been renewed interest in this therapy with the advent of laparoscopic surgery.

Indications for Surgical Treatment

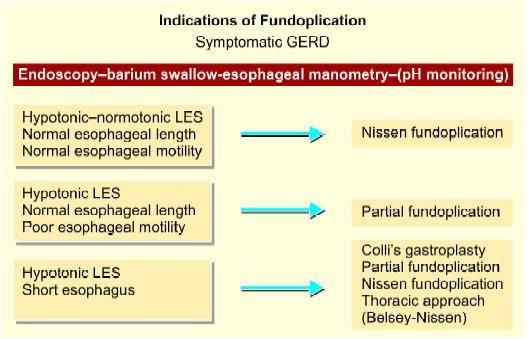

Currently, there is increasing interest in the surgical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). There are a number of reasons for this. Despite the fact that current medical management is very effective for the majority a small number of patients do not get complete relief of symptoms. Secondly, some patients, particularly those who are in their twenties or thirties, face the prospect of a lifetime of continuous proton pump inhibitor therapy with the possible risk of, as yet, unknown side effects. In addition, the laparoscopic approach with its benefits of reduced operative trauma and less time off work has become more commonplace. As a consequence, general practitioners and gastroenterologists are more ready to refer patients with disabling symptoms for surgical treatment. The gold standard antireflux operation is undoubtedly the Nissen type of total fundoplication and many studies have affirmed its effectiveness in controlling acid reflux. However, new symptoms after fundoplication such as gas bloat and dysphagia, which probably result from a hyper-competent lower esophageal sphincter produced by the Nissen operation, are common.

Concerning the indication for surgery, a distinction between heartburn and regurgitation symptoms is considered important (medical treatment appears to be more effective for heartburn than for regurgitation). Even after successful medical acid suppression, the patient can have recurrent symptoms of epigastric pain and retrosternal pressure as well as food regurgitation due to an incompetent cardia, insufficient peristalsis, or a large hiatal hernia.

Surgical therapy should be considered in individuals with documented GERD who:

• Refractory to medical management

• Associated with hiatus hernia

• Intolerance to PPH or H2 receptors

• Not compliant to medical therapy

• Have complications of GERD, e.g. Barrett’s esophagus, stricture, grade 3 or 4 esophagitis

• Atypical symptoms like Asthma, hoarseness, cough, chest pain, and aspiration.

A study has shown those patients resistant to antisecretory treatment are not a good candidate for antireflux surgery.

Methods of Fundoplication

• The classical open methods

• The modern laparoscopic techniques.

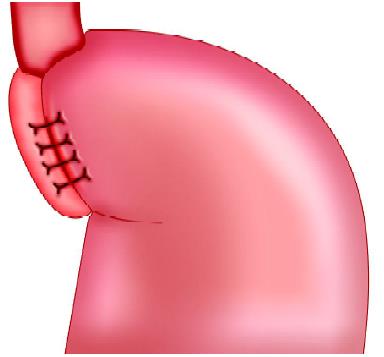

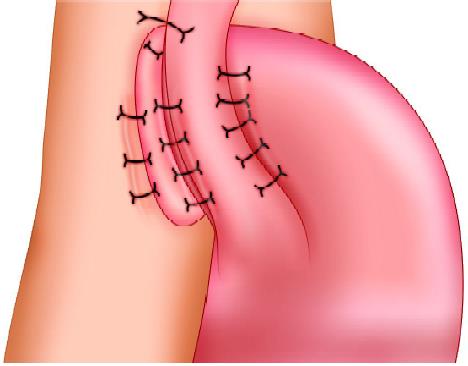

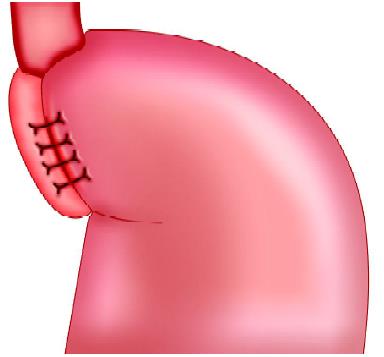

Laparoscopic fundoplication is a safe procedure and can provide less postoperative morbidity in experienced hands. This is a surgical procedure done for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Fundus of the stomach which is on the left of the esophagus and main portion of the stomach is wrapped around the back of the esophagus until it is once again in front of this structure. The portion of the fundus that is now on the right side of the esophagus is sutured to the portion on the left side to keep the wrap in place. The fundoplication resembles a buttoned shirt collar. The collar is the fundus wrap and the neck represents the esophagus imbricated into the wrap. This has the effect of creating a one-way valve in the esophagus to allow food to pass into the stomach, but prevent stomach acid from flowing into the esophagus and thus prevent GERD. Laparoscopic fundoplication is a useful method for reducing hospital stay, complications, and return to normal activity.

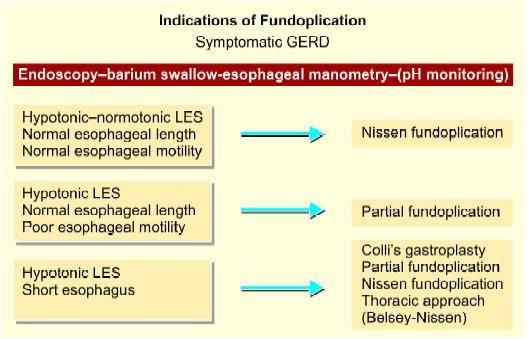

Types of Fundoplication Surgery

Laparoscopic fundoplication has become the standard surgical method of treating gastroesophageal reflux disease. Although Nissen total fundoplication is the most commonly performed procedure, partial fundoplication, either anterior or posterior, is becoming more acceptable because of a suggested lower risk of long-term side effects. The 360° Nissen fundoplication (NF) has been the standard operation for gastroesophageal reflux but is associated with substantial rates of, “gas bloat,” gagging and dysphasia. Toupet fundoplication (TF), a 270° posterior wrap, has fewer complications, and its outcome is compared with Nissen fundoplication is favorable both in children as well as adults. Although Nissen total fundoplication is the most commonly performed procedure, partial fundoplication, either anterior or posterior, is becoming more acceptable because of the lower risk of long-term complications. Dor in 1962 described anterior fundoplication as an antireflux operation for patients who had a Heller’s myotomy for achalasia. In the 1970s, Watson developed an operation for a patient suffering from GERD.

Selection of type of fundoplication

Nissen fundoplication (NF)

Toupet fundoplication (TF), a 270° wrap

Most surgeons believe that the Toupet fundoplication (TF), a 270° posterior wrap originally described in conjunction with myotomy for achalasia, has fewer complications, and its long-term outcome in compared with Nissen fundoplication is favorable both in children as well as adults. This article describes a technique of laparoscopic posterior Toupet fundoplication.

The main tasks of this operation consist of:

• Preparation of the patient

• Creation of pneumoperitoneum. Insertion of port

• Diagnostic laparoscopy and dissection of visceral peritoneum

• Mobilization of 5 cm intra-abdominal esophagus

• Fundus pull from below the esophagus

• Insertion of posterior sutures to tighten the crural opening

• Fixation of the fundus to the left crura

• Fixation of the fundus with the right crura

• Fixation of the fundus with the esophagus. Inspection of tightness of fundoplication

• Irrigation and suction of operating field

• Final diagnostic laparoscopy for any bowel injury or hemorrhage

• Removal of the instrument with the complete exit of CO2. Closure of wound.

Patient Selection

Many patients have symptoms palliated by lifestyles like diet and exercise, others by simple medication, and some by strong medication like proton pump inhibitors. A certain proportion of patient has refractory or long-term symptoms, and operation can be considered in this group of patients. As reflux symptoms are frequent and variable, it is wise to obtain both ambulatory 24 pH-metry and esophageal motility studies prior to surgery. Upper GI endoscopies should be performed in all patients.

Operative Technique

Patient Position

The patient is placed on the operating table with the legs in stirrups, the knees slightly bent and the hips flexed approximately 10°. The operating table is tilted head up by approximately 15°. A compression bandage is used on the leg during the operation to prevent thromboembolism. The surgeon stands between the patient’s legs. The first assistant, whose main task is to position the video camera, sits on the surgeon's left side. The instrument trolley is placed on the patient’s left allowing the scrub nurse to assist with placing the appropriate instruments in the operating ports. Television monitors are positioned on either side of the top end of the operating table at a suitable height for a surgeon, anesthetist, and assistant to see the procedure.

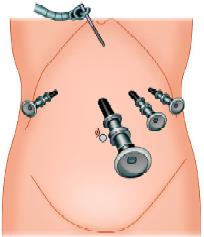

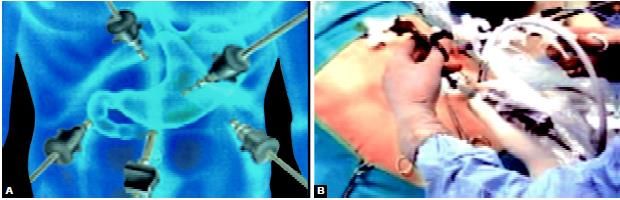

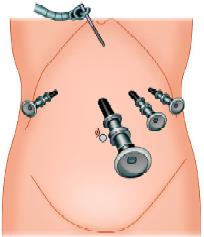

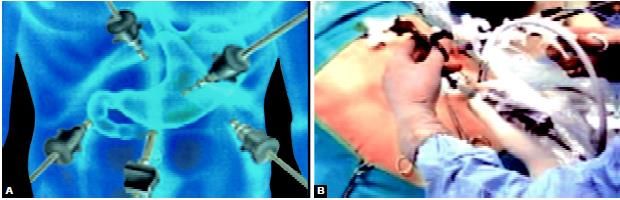

Port Position

The 10 mm camera (port 1) is placed in the midline approximately 5 cm above the umbilicus; this position will vary depending on the build of the patient. After inserting the camera, a 5 mm port (2) is inserted in the right upper quadrant 8 to 10 cm from the midline. A port (3), with a variable 5 to 10 mm diaphragm, is placed in the left upper quadrant—a mirror image of the one on the patient’s right.

This allows both 5 mm and 10 mm instruments to be used through the same cannula without changing ports. A further 5 mm port (4) is positioned in the left anterior axillary line immediately below the costal margin. This port is mainly used for a forceps which will hold the tape encircling the esophagus. Liver retraction used to be one of the more problematic aspects of laparoscopic fundoplication. In our experience, these difficulties have been largely overcome by the use of the Nathanson liver retractor.

Port position in fundoplication

Alternate port position in laparoscopic fundoplication show in the image below.

Alternative port position in laparoscopic fundoplication

Procedure

Tissue Dissection and Mobilization

Dissection starts at the avascular portion of the lesser omentum above the hepatic branch of the vagus. The dissection is continued carefully up to the hiatus, which can be seen through the defect created. An opening is created in the lesser omentum, above the hepatic branch of the vagus to allow better access to the hiatus. The right crus is dissected using electrosurgery and scissors to identify the plane between the crus and surrounding loose areolar tissues. The loose areolar tissue around the esophagus is exposed and secures the bleeding from any blood vessels visible during the mobilization of the esophagus. Always remember not to injure the esophageal wall and vagal fibers when dissecting this area around the esophagus. The space between the hiatus and the anterior aspect of the esophagus is developed using fine dissection by scissors to divide blood vessels crossing this space.

Lesser Sac Opened

The posterior aspect of the left crus is identified as it meets the right crus and dissection of its surface commences especially the peritoneal covering over the margin of right crus is dissected down to the fundus from the diaphragm known as Rosetti dissection technique. Dissection of the posterior aspect of the left crus is done by lifting the intraabdominal esophagus forwards with a blunt instrument. A sling is fed into the jaws of the grasping forceps and then pulled around behind the esophagus.

Sling insertion

Sling is passed through a separate puncture wound from the abdominal wall without a port. A grasping forceps is inserted through one of the port to hold the sling so that the esophagus can be manipulated. Dissection surroundings of the esophagus in the posterior mediastinum should for approximately 5 to 6 cm. Mobilization of the esophagus and stomach should be sufficient enough to have a good floppy fundus for a wrap.

• The next step is to pull the fundus from behind the esophagus to form a wrap.

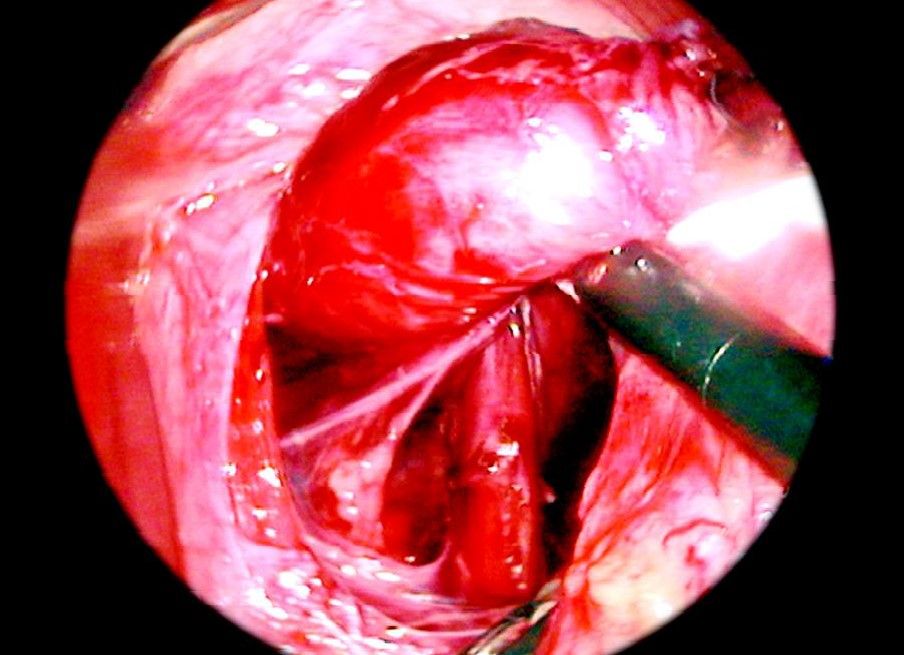

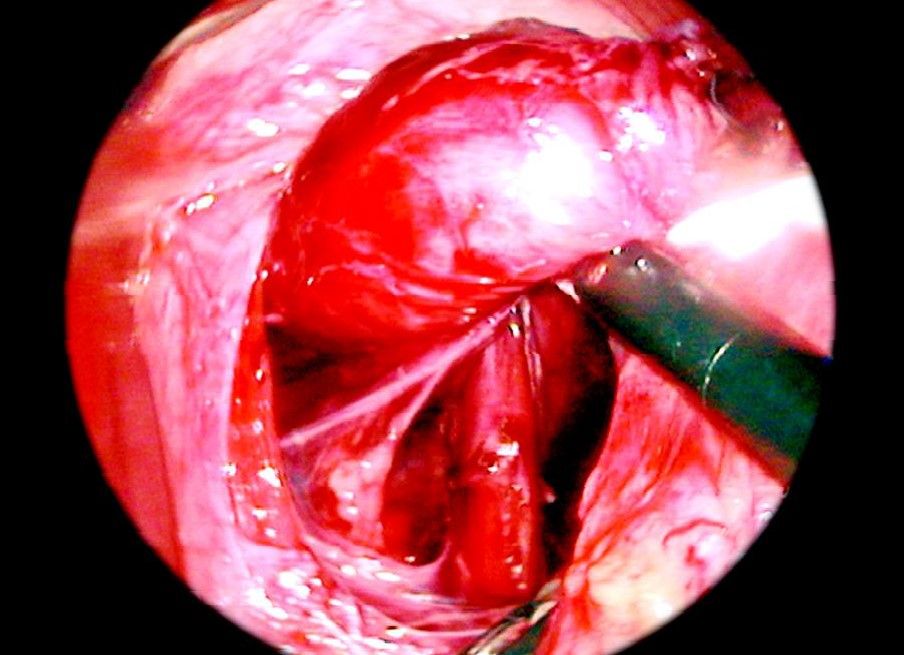

Fundus Pull

After mobilizing the fundus nicely the tip of the fundus is pulled by one of the grasper introduced through below and right side of the esophagus.

The mobilization of the stomach should be adequate to give a floppy fundus for plication otherwise patient may develop dysphagia. One stay suture may be applied to the fundus to hold it in place or one of the graspers may be used to keep it pulled. The next step is crural repair.

Crural Approximation

Crura should be approximated behind the esophagus using two or three sutures of 2/0 braided polyamide on a 30 mm needle using Tumble Square Knot. A further one or two sutures are inserted in the same way, at about 1 cm intervals and tied using Tumble square knot. It is important not to make the crural opening too tight since this will produce dysphagia.

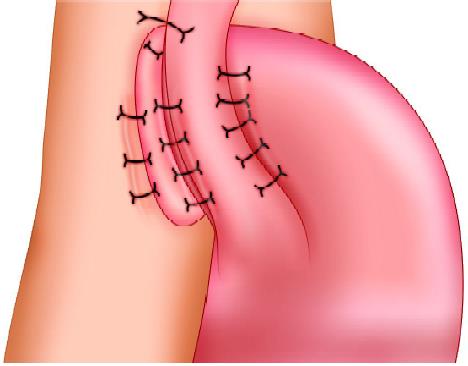

Fundoplication

The suture is applied which involves a 1 cm bite of the seromuscular layer of the gastric fundus, which is sutured to the anterior aspect of the left crus. Since the fundus lays some way from the left crus, the slip reef knot or Tumble square knot is particularly valuable for this suture. After this, a further suture is placed between the fundus and the left anterior aspect of the hiatus. The next suture is placed between the fundus and the right anterior aspect of the hiatus.

Further three sutures are then positioned at approximately 1 cm intervals to the posterior fundus and the right crus. The sling used for esophageal retraction is removed. One or two sutures may be placed to fix the side of the esophagus with the wrapped portion of the stomach. But always remember the wrap is not in place due to these sutures. The suture of the fundus with crura actually holds the wrap in position. Never take a full-thickness bite on the esophagus with Endoski needle otherwise there is always a chance of perforation of the esophagus.

Ending of the Operation

The abdomen should be examined for any possible bowel injury or hemorrhage. The instrument and then port should be removed carefully. Remove telescope leaving the gas valve of the umbilical port open to let out all the gas. Close the wound with suture. Use vicryl for rectus and unabsorbable intradermal or stapler for the skin. Apply adhesive sterile dressing over the wound.

A patient may be discharged 2 days after an operation if everything goes well. The patient may have slight dysphagia initially but usually resolves after 6 weeks. The patient has any complaint of dysphagia should be examined endoscopically after 3 to 4 weeks of operation.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as the failure of the antireflux barrier, allowing abnormal reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. It is a mechanical disorder that is caused by a defective lower esophageal sphincter, a gastric emptying disorder, or failed esophageal peristalsis. Gastroesophageal reflux is one of the most common digestive symptoms. Exposure of the esophageal mucosa to acid, enzymes and other digestive secretions, leads to acute and chronic inflammation, with pain, and ulceration or stricture formation if untreated.

Heartburn occurs in 5 to 45 percent of adults in western countries, depending on the frequency of symptoms 30 to 45 percent suffer from symptoms once a month and 5 to 10 percent every day. The majority of patients suffering from GERD experience minor symptoms for which they do not seek medical attention. Age does not seem to have an impact on the frequency of GERD symptoms, and no causal factor has been identified. Esophagitis due to reflux occurs in approximately 2 percent of the global population. It is the most frequent form of lesion detected on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, occurring more frequently than gastric ulcers or duodenal ulcers. GERD is often a chronic ailment. After a 5 to 10 years follow-up, about two-thirds of patients complain of persistent symptoms requiring occasional or continuous treatment.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GERD is multifactorial, although it is usually due to the weakening of the anatomical or functional gastroesophageal barrier located at the esophagogastric junction. Injury to the esophageal mucosa by acid-peptic gastric secretions, while secondary to this weakening, plays a major role in the development of GERD symptoms and lesions. In fact, suppressing the gastric acid secretion, which is the usual treatment of this ailment, leads to the disappearance of symptoms and healing of lesions in almost all cases. GERD is, therefore acid dependent.

Symptoms

• Heartburn (Retrosternal burning)

• Regurgitation

• Pain

• Respiratory symptoms.

Diagnostic Test

• Endoscopy

• Barium swallow

• Esophageal transit + /- manometry

• pH monitoring.

Treatment of GERD

Medical therapy is the first line of management. Esophagitis will heal in approximately 90 percent of cases with intensive medical therapy. However, symptoms recur in more than 80 percent of cases within one year of drug withdrawal. Since it is a chronic condition, medical therapy involving acid suppression and/or promotility agents may be required for the rest of a patient’s life. Despite the fact that current medical management is very effective for the majority, a small number of patients do not get complete relief of symptoms. Currently, there is increasing interest in the surgical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

The goal of surgical therapy is to recreate an antireflux barrier. It is the only treatment capable of changing the natural history of GERD. There has been renewed interest in this therapy with the advent of laparoscopic surgery.

Indications for Surgical Treatment

Currently, there is increasing interest in the surgical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). There are a number of reasons for this. Despite the fact that current medical management is very effective for the majority a small number of patients do not get complete relief of symptoms. Secondly, some patients, particularly those who are in their twenties or thirties, face the prospect of a lifetime of continuous proton pump inhibitor therapy with the possible risk of, as yet, unknown side effects. In addition, the laparoscopic approach with its benefits of reduced operative trauma and less time off work has become more commonplace. As a consequence, general practitioners and gastroenterologists are more ready to refer patients with disabling symptoms for surgical treatment. The gold standard antireflux operation is undoubtedly the Nissen type of total fundoplication and many studies have affirmed its effectiveness in controlling acid reflux. However, new symptoms after fundoplication such as gas bloat and dysphagia, which probably result from a hyper-competent lower esophageal sphincter produced by the Nissen operation, are common.

Concerning the indication for surgery, a distinction between heartburn and regurgitation symptoms is considered important (medical treatment appears to be more effective for heartburn than for regurgitation). Even after successful medical acid suppression, the patient can have recurrent symptoms of epigastric pain and retrosternal pressure as well as food regurgitation due to an incompetent cardia, insufficient peristalsis, or a large hiatal hernia.

Surgical therapy should be considered in individuals with documented GERD who:

• Refractory to medical management

• Associated with hiatus hernia

• Intolerance to PPH or H2 receptors

• Not compliant to medical therapy

• Have complications of GERD, e.g. Barrett’s esophagus, stricture, grade 3 or 4 esophagitis

• Atypical symptoms like Asthma, hoarseness, cough, chest pain, and aspiration.

A study has shown those patients resistant to antisecretory treatment are not a good candidate for antireflux surgery.

Methods of Fundoplication

• The classical open methods

• The modern laparoscopic techniques.

Laparoscopic fundoplication is a safe procedure and can provide less postoperative morbidity in experienced hands. This is a surgical procedure done for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Fundus of the stomach which is on the left of the esophagus and main portion of the stomach is wrapped around the back of the esophagus until it is once again in front of this structure. The portion of the fundus that is now on the right side of the esophagus is sutured to the portion on the left side to keep the wrap in place. The fundoplication resembles a buttoned shirt collar. The collar is the fundus wrap and the neck represents the esophagus imbricated into the wrap. This has the effect of creating a one-way valve in the esophagus to allow food to pass into the stomach, but prevent stomach acid from flowing into the esophagus and thus prevent GERD. Laparoscopic fundoplication is a useful method for reducing hospital stay, complications, and return to normal activity.

Types of Fundoplication Surgery

Laparoscopic fundoplication has become the standard surgical method of treating gastroesophageal reflux disease. Although Nissen total fundoplication is the most commonly performed procedure, partial fundoplication, either anterior or posterior, is becoming more acceptable because of a suggested lower risk of long-term side effects. The 360° Nissen fundoplication (NF) has been the standard operation for gastroesophageal reflux but is associated with substantial rates of, “gas bloat,” gagging and dysphasia. Toupet fundoplication (TF), a 270° posterior wrap, has fewer complications, and its outcome is compared with Nissen fundoplication is favorable both in children as well as adults. Although Nissen total fundoplication is the most commonly performed procedure, partial fundoplication, either anterior or posterior, is becoming more acceptable because of the lower risk of long-term complications. Dor in 1962 described anterior fundoplication as an antireflux operation for patients who had a Heller’s myotomy for achalasia. In the 1970s, Watson developed an operation for a patient suffering from GERD.

Selection of type of fundoplication

Nissen fundoplication (NF)

Toupet fundoplication (TF), a 270° wrap

Most surgeons believe that the Toupet fundoplication (TF), a 270° posterior wrap originally described in conjunction with myotomy for achalasia, has fewer complications, and its long-term outcome in compared with Nissen fundoplication is favorable both in children as well as adults. This article describes a technique of laparoscopic posterior Toupet fundoplication.

The main tasks of this operation consist of:

• Preparation of the patient

• Creation of pneumoperitoneum. Insertion of port

• Diagnostic laparoscopy and dissection of visceral peritoneum

• Mobilization of 5 cm intra-abdominal esophagus

• Fundus pull from below the esophagus

• Insertion of posterior sutures to tighten the crural opening

• Fixation of the fundus to the left crura

• Fixation of the fundus with the right crura

• Fixation of the fundus with the esophagus. Inspection of tightness of fundoplication

• Irrigation and suction of operating field

• Final diagnostic laparoscopy for any bowel injury or hemorrhage

• Removal of the instrument with the complete exit of CO2. Closure of wound.

Patient Selection

Many patients have symptoms palliated by lifestyles like diet and exercise, others by simple medication, and some by strong medication like proton pump inhibitors. A certain proportion of patient has refractory or long-term symptoms, and operation can be considered in this group of patients. As reflux symptoms are frequent and variable, it is wise to obtain both ambulatory 24 pH-metry and esophageal motility studies prior to surgery. Upper GI endoscopies should be performed in all patients.

Operative Technique

Patient Position

The patient is placed on the operating table with the legs in stirrups, the knees slightly bent and the hips flexed approximately 10°. The operating table is tilted head up by approximately 15°. A compression bandage is used on the leg during the operation to prevent thromboembolism. The surgeon stands between the patient’s legs. The first assistant, whose main task is to position the video camera, sits on the surgeon's left side. The instrument trolley is placed on the patient’s left allowing the scrub nurse to assist with placing the appropriate instruments in the operating ports. Television monitors are positioned on either side of the top end of the operating table at a suitable height for a surgeon, anesthetist, and assistant to see the procedure.

Port Position

The 10 mm camera (port 1) is placed in the midline approximately 5 cm above the umbilicus; this position will vary depending on the build of the patient. After inserting the camera, a 5 mm port (2) is inserted in the right upper quadrant 8 to 10 cm from the midline. A port (3), with a variable 5 to 10 mm diaphragm, is placed in the left upper quadrant—a mirror image of the one on the patient’s right.

This allows both 5 mm and 10 mm instruments to be used through the same cannula without changing ports. A further 5 mm port (4) is positioned in the left anterior axillary line immediately below the costal margin. This port is mainly used for a forceps which will hold the tape encircling the esophagus. Liver retraction used to be one of the more problematic aspects of laparoscopic fundoplication. In our experience, these difficulties have been largely overcome by the use of the Nathanson liver retractor.

Port position in fundoplication

Alternate port position in laparoscopic fundoplication show in the image below.

Alternative port position in laparoscopic fundoplication

Procedure

Tissue Dissection and Mobilization

Dissection starts at the avascular portion of the lesser omentum above the hepatic branch of the vagus. The dissection is continued carefully up to the hiatus, which can be seen through the defect created. An opening is created in the lesser omentum, above the hepatic branch of the vagus to allow better access to the hiatus. The right crus is dissected using electrosurgery and scissors to identify the plane between the crus and surrounding loose areolar tissues. The loose areolar tissue around the esophagus is exposed and secures the bleeding from any blood vessels visible during the mobilization of the esophagus. Always remember not to injure the esophageal wall and vagal fibers when dissecting this area around the esophagus. The space between the hiatus and the anterior aspect of the esophagus is developed using fine dissection by scissors to divide blood vessels crossing this space.

Lesser Sac Opened

The posterior aspect of the left crus is identified as it meets the right crus and dissection of its surface commences especially the peritoneal covering over the margin of right crus is dissected down to the fundus from the diaphragm known as Rosetti dissection technique. Dissection of the posterior aspect of the left crus is done by lifting the intraabdominal esophagus forwards with a blunt instrument. A sling is fed into the jaws of the grasping forceps and then pulled around behind the esophagus.

Sling insertion

Sling is passed through a separate puncture wound from the abdominal wall without a port. A grasping forceps is inserted through one of the port to hold the sling so that the esophagus can be manipulated. Dissection surroundings of the esophagus in the posterior mediastinum should for approximately 5 to 6 cm. Mobilization of the esophagus and stomach should be sufficient enough to have a good floppy fundus for a wrap.

• The next step is to pull the fundus from behind the esophagus to form a wrap.

Fundus Pull

After mobilizing the fundus nicely the tip of the fundus is pulled by one of the grasper introduced through below and right side of the esophagus.

The mobilization of the stomach should be adequate to give a floppy fundus for plication otherwise patient may develop dysphagia. One stay suture may be applied to the fundus to hold it in place or one of the graspers may be used to keep it pulled. The next step is crural repair.

Crural Approximation

Crura should be approximated behind the esophagus using two or three sutures of 2/0 braided polyamide on a 30 mm needle using Tumble Square Knot. A further one or two sutures are inserted in the same way, at about 1 cm intervals and tied using Tumble square knot. It is important not to make the crural opening too tight since this will produce dysphagia.

Fundoplication

The suture is applied which involves a 1 cm bite of the seromuscular layer of the gastric fundus, which is sutured to the anterior aspect of the left crus. Since the fundus lays some way from the left crus, the slip reef knot or Tumble square knot is particularly valuable for this suture. After this, a further suture is placed between the fundus and the left anterior aspect of the hiatus. The next suture is placed between the fundus and the right anterior aspect of the hiatus.

Further three sutures are then positioned at approximately 1 cm intervals to the posterior fundus and the right crus. The sling used for esophageal retraction is removed. One or two sutures may be placed to fix the side of the esophagus with the wrapped portion of the stomach. But always remember the wrap is not in place due to these sutures. The suture of the fundus with crura actually holds the wrap in position. Never take a full-thickness bite on the esophagus with Endoski needle otherwise there is always a chance of perforation of the esophagus.

Ending of the Operation

The abdomen should be examined for any possible bowel injury or hemorrhage. The instrument and then port should be removed carefully. Remove telescope leaving the gas valve of the umbilical port open to let out all the gas. Close the wound with suture. Use vicryl for rectus and unabsorbable intradermal or stapler for the skin. Apply adhesive sterile dressing over the wound.

A patient may be discharged 2 days after an operation if everything goes well. The patient may have slight dysphagia initially but usually resolves after 6 weeks. The patient has any complaint of dysphagia should be examined endoscopically after 3 to 4 weeks of operation.