Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Laparoscopic surgery has undergone rapid development in recent years. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was first performed in 1985. Since the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy into general practice in 1990, it has rapidly become the dominant procedure for gallbladder surgery. By the end of the decade, laparoscopic cholecystectomy had spread throughout the world. The importance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy was the cultural change it engendered rather than the operation it replaced. In terms of technique, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now the gold standard for the treatment of symptomatic gallstone disease. It is most commonly performed minimal access surgery by general surgeons worldwide. In Europe and America, 98 percent of all the cholecystectomy is performed by laparoscopy. The credit of popularizing minimal access surgery goes to laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This is the most popular and most accepted minimal access surgical procedure worldwide. Laparoscopic surgery has expanded from gallbladder surgery to virtually every operation in the abdominal cavity.

Indications

• Cholelithiasis

• Mucocele gallbladder

• Empyema gallbladder

• Cholesterosis

• Typhoid carrier

• Porcelain gallbladder

• Acute cholecystitis (calculous and acalculous)

• Adenomatous gallbladder polyps

• As part of other procedures viz. Whipple’s procedure.

Contraindications

• Hemodynamic instability

• Uncorrected coagulopathy

• Generalized peritonitis

• Severe cardiopulmonary disease

• Abdominal wall infection

• Multiple previous upper abdominal procedures

• Late pregnancy.

The general anesthesia and the pneumoperitoneum required as part of the laparoscopic procedure do increase the risk in certain groups of patients. Most surgeons would not recommend laparoscopy in those with pre-existing disease conditions. Patients with severe cardiac diseases and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) should not be considered a good candidate for laparoscopy. The laparoscopic cholecystectomy may also be more difficult in patients who have had previous upper abdominal surgery. The elderly may also be at increased risk for complications with general anesthesia combined with pneumoperitoneum.

Advantage of Laparoscopic Approach

• Cosmetically better outcome

• Less tissue dissection and disruption of tissue planes

• Less pain postoperatively

• Low intraoperative and postoperative complications in experienced hand

• Early return to work.

Preoperative Investigations

Apart from routine preoperative investigations, in fit patients, the only investigations needed are ultrasound examination. Although practiced in some centers, intravenous cholangiography may not be confirmative and is attended with the risk of anaphylactic reactions.

Patient Position

The patient is operated in the supine position with a steep head- up and left tilt. This typical positioning of laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be achieved once the pneumoperitoneum has been established. The patient is then placed in reverse Trendelenburg’s position and rotated to the left to give maximal exposure to the right upper quadrant.

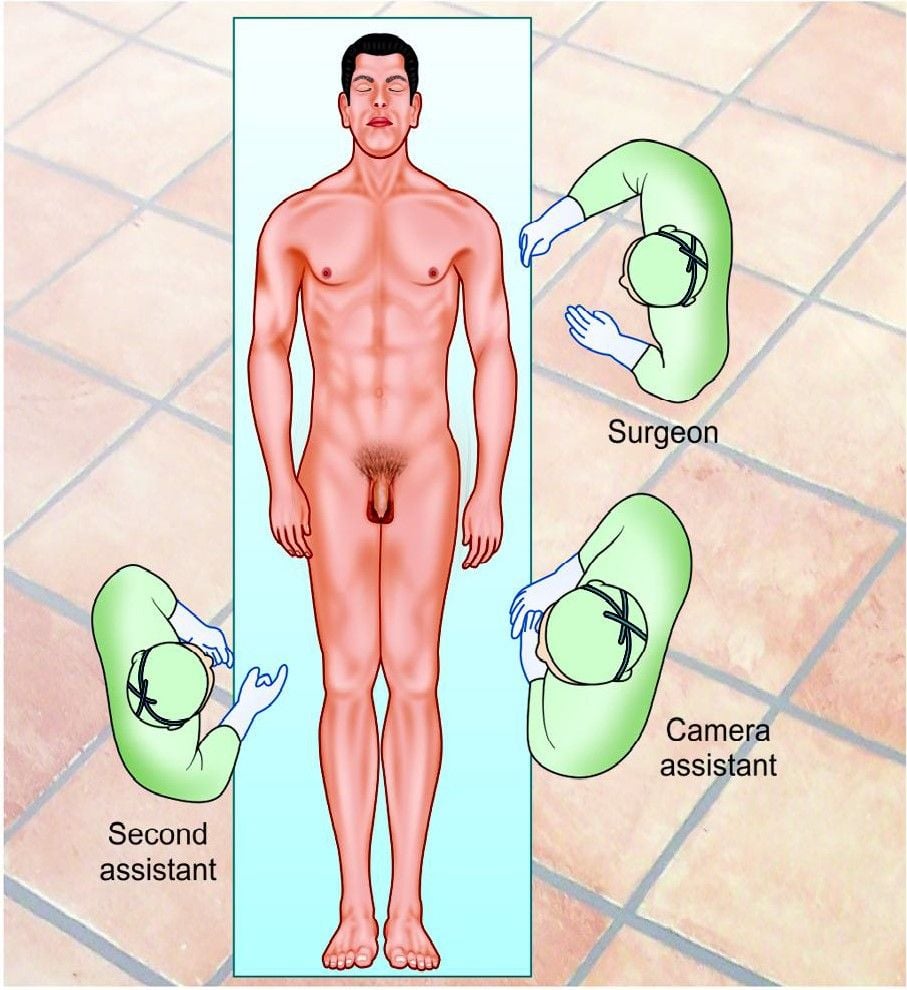

Position of Surgical Team

The surgeon stands on the left side of the patient with the scrub nurse-camera holder-assistant. One assistant stand right to the patient and should hold the fundus grasping forceps.

Position of the surgical team

Tasks Analysis

• Preparation of the patient

• Creation of pneumoperitoneum

• Insertion of ports

• Diagnostic laparoscopy

• Dissection of visceral peritoneum

• Dissection of Calot’s triangle

• Clipping and division of cystic duct and artery

• Dissection of the gallbladder from the liver bed

• Extraction of the gallbladder and any spilled stone

• Irrigation and suction of operating field

• Final diagnostic laparoscopy

• Removal of the instrument with the complete exit of CO2

• Closure of wound.

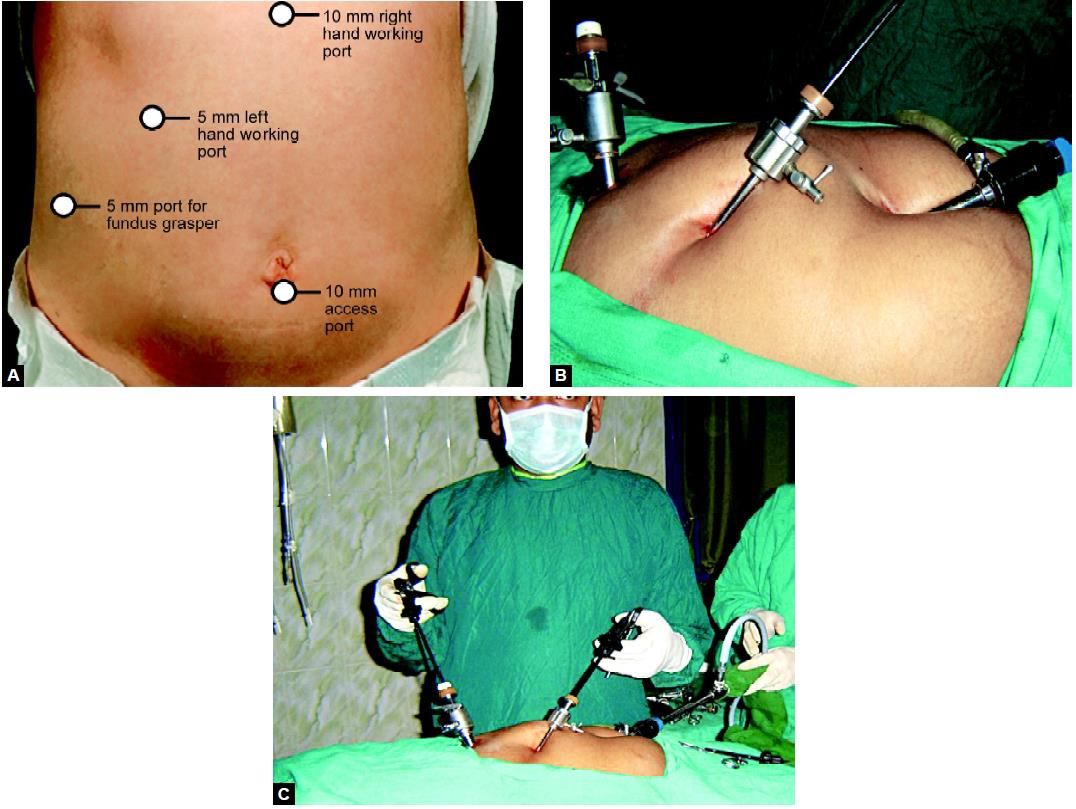

Port Location

Four ports are used: optical (10 mm), one 5 mm, one 10 mm operating, and one 5.0 mm assisting port. The optical port is at or near the umbilicus and routinely a 30° laparoscope is used. Some surgeons who have started laparoscopy earlier is more comfortable with the 0° telescope. The laparoscope is inserted through a 10 mm umbilical port and the abdominal cavity is explored for any obvious abnormalities. The secondary ports are then placed under direct visualization with the laparoscope. The surgeon places a 10 mm trocar in the midline and left to the falciform ligament at the epigastrium. Two 5 mm ports one subcostal trocar in the right upper quadrant and another 5 mm trocar, lower, near the right anterior axillary line are placed.

(A) Ideal port position for laparoscopic cholecystectomy; (B and C) Port position of cholecystectomy

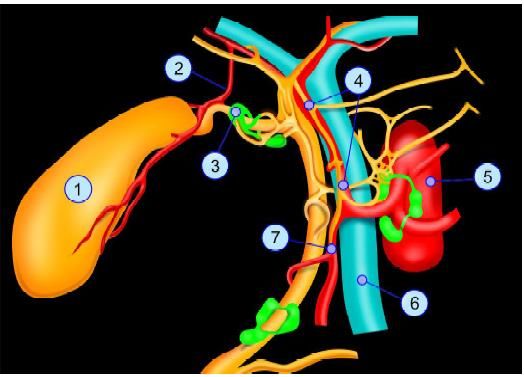

Laparoscopic Anatomy

The laparoscopic view of the right upper quadrant on the first look will demonstrate primarily the subphrenic spaces, the abdominal surface of the diaphragm, and diaphragmatic surface of the liver. The fundus of the gallbladder can be seen popping from the inferior surface of the liver. The falciform ligament is seen as a prominent dividing point between left subphrenic space and the right subphrenic space. As the gallbladder is elevated and retracted towards the diaphragm, adhesion to the omentum or duodenum and transverse colon is seen.

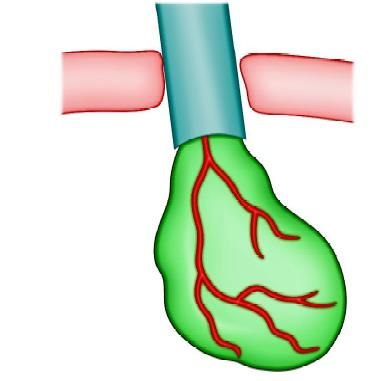

Topographic anatomy of gallbladder: (1) Gallbladder; (2) Cystic artery; (3) Mascagni lymph node; (4) Proper hepatic artery; (5) Abdominal aorta; (6) Portal vein; (7) Gastroduodenal artery

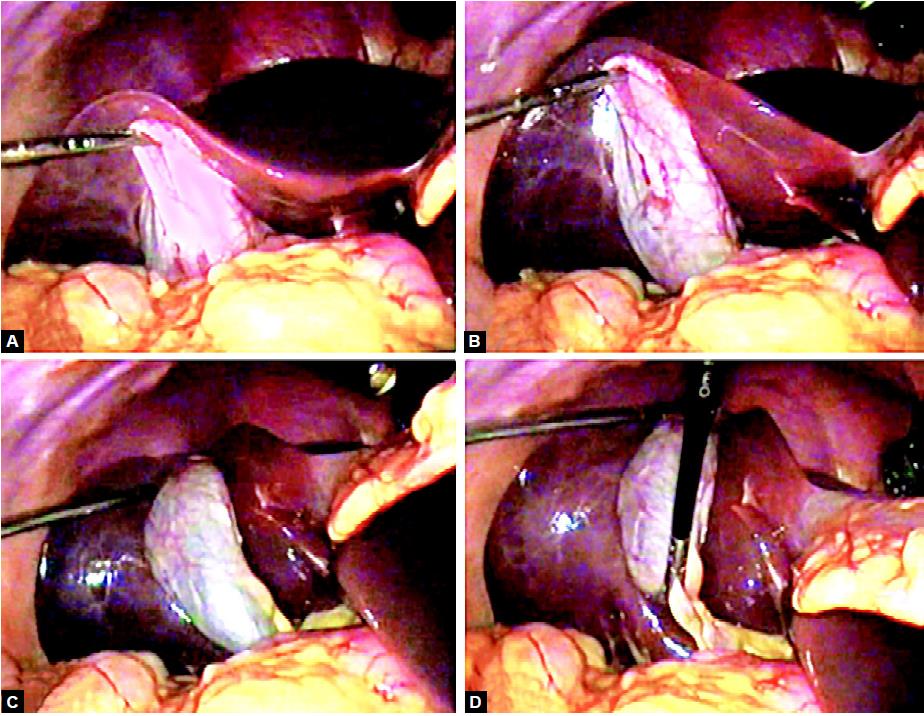

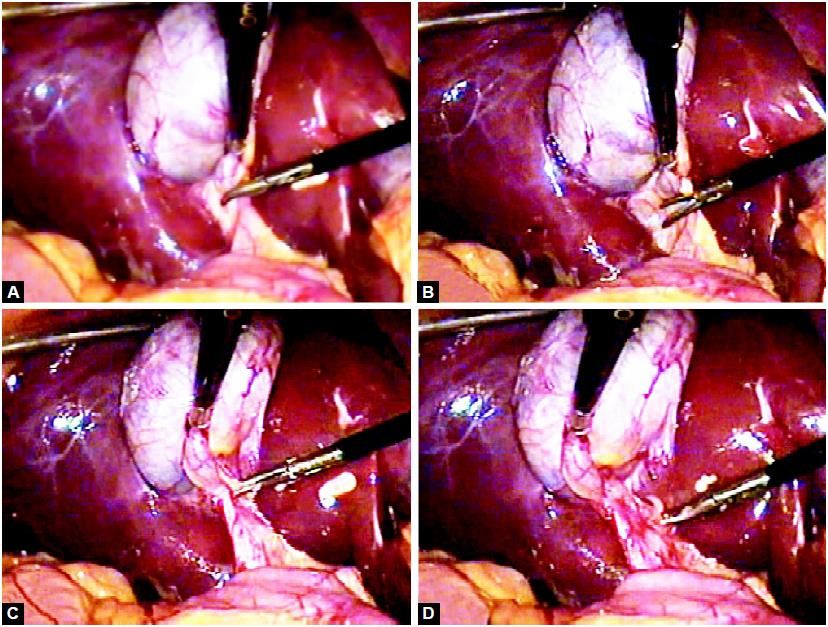

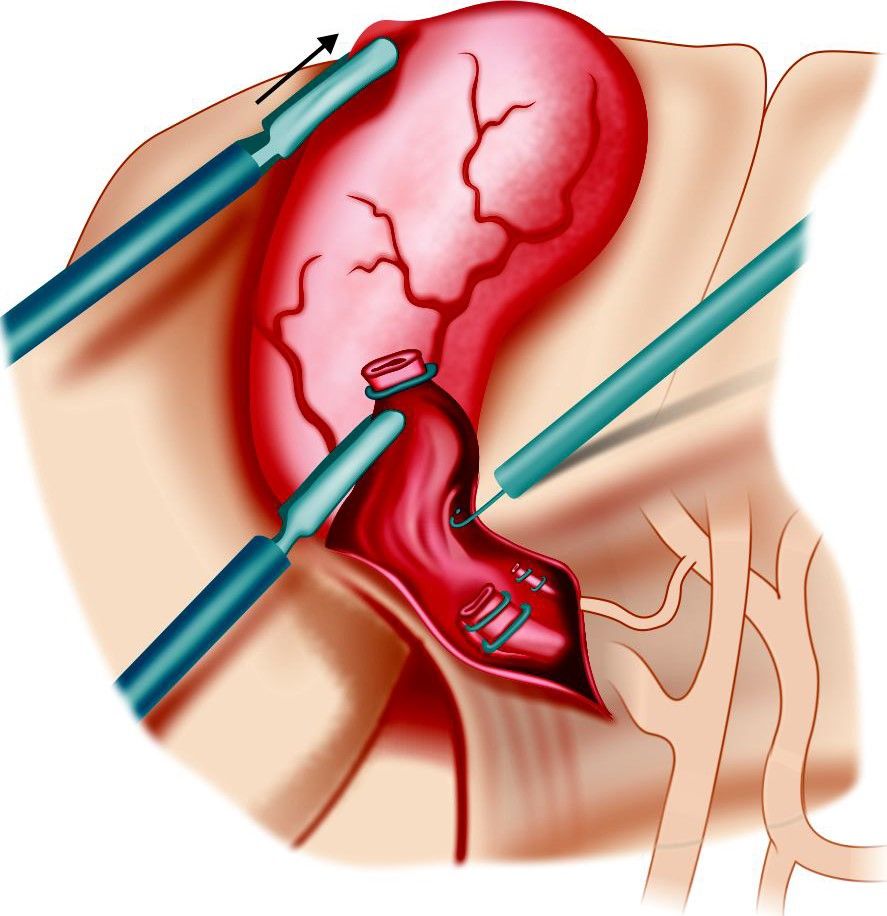

Exposure of Gallbladder and Cystic Pedicle

A grasper is used through the right lower 5 mm trocar to grasp the gallbladder fundus and retract it up over the liver edge to expose the entire length of the gallbladder. If there are adhesions to the gallbladder, they will need to be taken down using blunt and sharp dissection. With the entire gallbladder visualized, a second grasper is inserted through the other right upper quadrant trocar to grasp the gallbladder infundibulum and retract it up and to the right to expose the triangle of Calot.

Proper traction for exposure of cystic pedicle

Careful evaluation of the anatomy reveals whether it is partially intrahepatic, on a mesentery, or possesses a Phrygian cap or any other odd shape. Hartmann’s pouch should be identified and seen to be funneled down to continue as a tubular structure, the cystic duct. It is important to identify Hartmann’s pouch clearly because of most of the laparoscopic surgeon's clip and divide the cystic duct, high on its termination at Hartmann’s pouch, rather than attempting to trace the cystic duct’s junction with the common bile duct. Dissection of the junction of the cystic duct with the CBD increases the chance of traction injury and bleeding from small vessels and lymphatic.

The cystic artery can be seen if attention is given as it runs along the surface of gallbladder. A lymph node may be seen anterior to the cystic artery. The cystic artery gives off a small artery that supplies the cystic duct. This tiny twig often avulsed and bleeds at the time of creating a window between the artery and the duct. This bleeding stops when the cystic duct is clipped.

Adhesiolysis

Any adhesion should be cleared from the gallbladder. The surgeon uses a dissector through the epigastric trocar to tear the peritoneal attachments from the infundibulum. The attachments are taken down from high on the gallbladder, beginning laterally in order to help avoid injury to the common bile duct. Sharp dissection may be carried out with the help of scissors attached to the monopolar current. At the time of separating adhesion, the surgeon should try to be as near as possible towards gallbladder. The cystic pedicle is a triangular fold of peritoneum containing the cystic duct and artery, the cystic node, and a variable amount of fat. It has a superior and an inferior leaf which is continuous over the anterior edge formed by the cystic duct. An important consideration is the frequent anomalies of the structures contained between the two leaves (15–20%). The normal configuration is for an anterior cystic duct with the cystic artery situated posterosuperior and arising from the right hepatic artery usually behind the common bile duct.

Clearing adhesions by hook

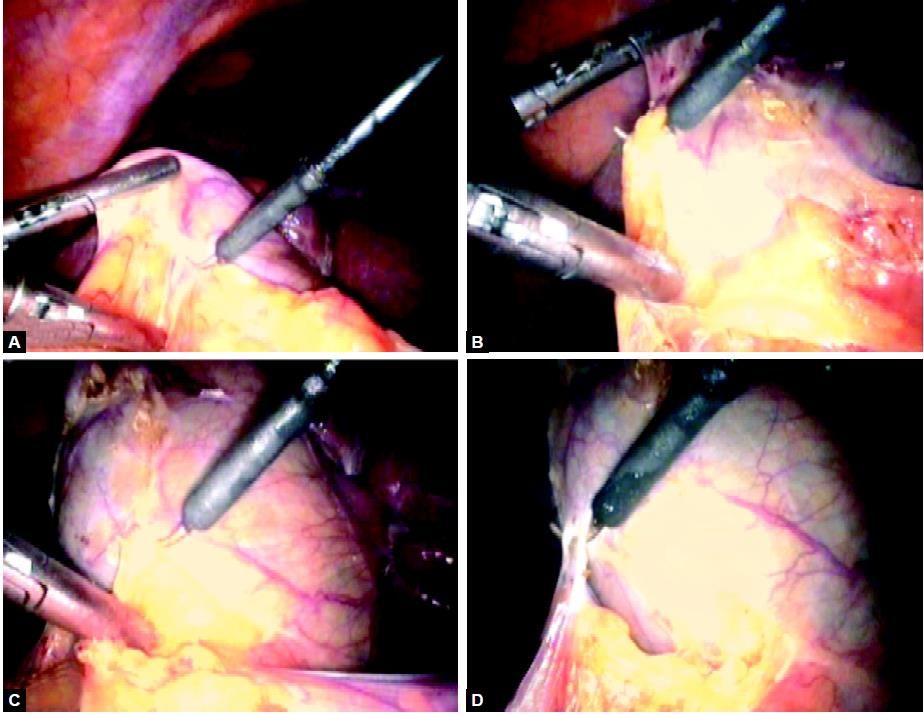

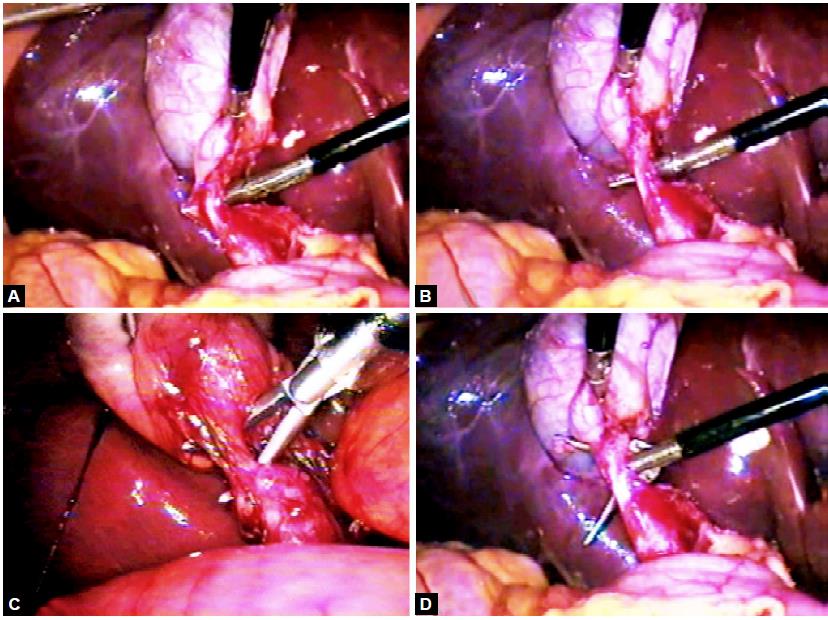

Dissection of Cystic Pedicle

The dissection of the cystic pedicle can be carried out with the two-handed technique. The dissection should be started with anteromedial traction by left-hand grasper placed on the anterior edge of Hartmann’s pouch. The anteromedial traction by the left hand will expose the posterior peritoneum. The peritoneum of the posterior leaf of the cystic pedicle is divided superficially as far back as the liver. The posterior leaf is better to dissect before anterior leaf because it is relatively less vascular and the bleeding if any, will not soil the anterior peritoneum, whereas if anterior peritoneum is tackled first, it may make the dissection area of posterior peritoneum filled with blood making dissection of this area difficult. Once the visceral peritoneum is dissected, a pledget mounted securely in a pledget holder is used for blunt dissection.

Dissection of cystic pedicle

Separation of Cystic Duct from Artery

Once the cystic duct is visualized, the dissector can be used to create a window in the triangle of Calot between the cystic duct and cystic artery. This window should be created high near the gallbladder-cystic duct junction to avoid injury to the common duct. The separation of the cystic duct anteriorly from the cystic artery behind can be performed by a Maryland's grasper by gently opening the jaw of Maryland between the duct and artery. The opening of the jaw of Maryland dissector should be in the line of duct never at a right angle to avoid injury of the artery behind. Sufficient length of the cystic duct and artery on the gallbladder side should be mobilized so that three clips can be applied.

The electrosurgical hook may be inserted into the window and hooked around the cystic duct. With an up and down movement, the hook is used to clear as much tissue as possible from the duct nearer to the cystic duct- gallbladder junction. Tissue that is not dissected free from the duct is retracted by the hook away from all structures and is divided using active cutting current. Depending on the length of the duct it is usually not necessary to dissect it all the way down to its junction with the common bile duct. In a similar fashion, the hook can be used to isolate the cystic artery for a length that is adequate enough to clip it.

The cystic duct is separated from the artery by creating a window

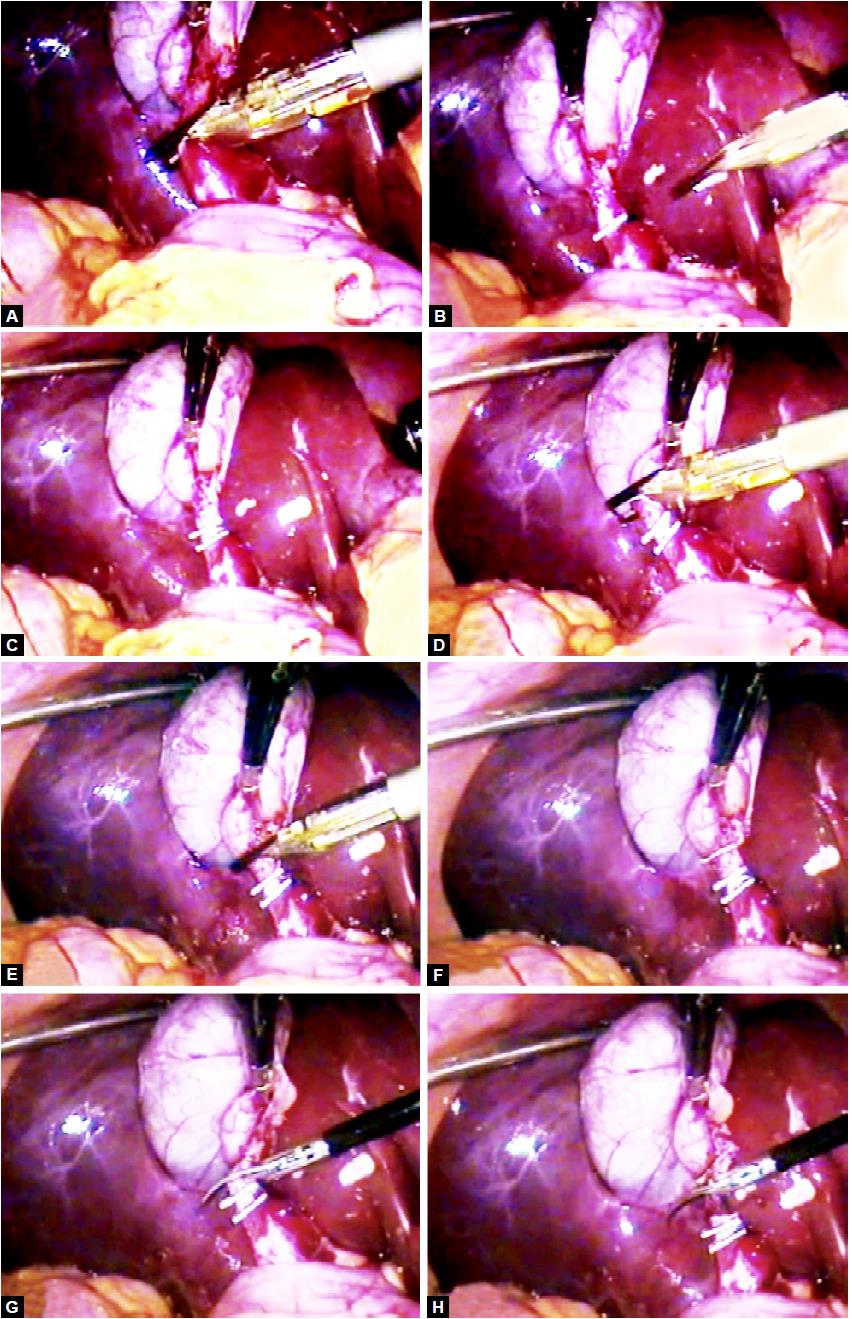

Clipping and Division of Cystic Duct

After isolating the cystic duct and artery, the clipper is introduced through the epigastric port and at least two clips are placed on the proximal side of the cystic duct. Care is taken not to place the clips too low because retraction can tent up the common bile duct or cause it to be obstructed. Another clip is placed on the gallbladder side of the cystic duct, leaving enough distance between the clips to divide it. In a similar fashion, clips are placed on the cystic artery, two proximally and one on the gallbladder side of the artery. The laparoscopic scissors are then used through the epigastric port to divide the cystic duct and artery between the clips. Both the jaw of scissors should be under vision.

The cystic duct is clipped and divided

Clipping and Division of Cystic Artery

The cystic artery is clipped and then divided by scissors. Two clips are placed proximally on the cystic artery and one clip is applied distally. The artery is then grasped with a duckbill grasper on the gallbladder wall and then divided between the second and third clips.

The cystic artery is clipped and divided

Operative Cholangiogram

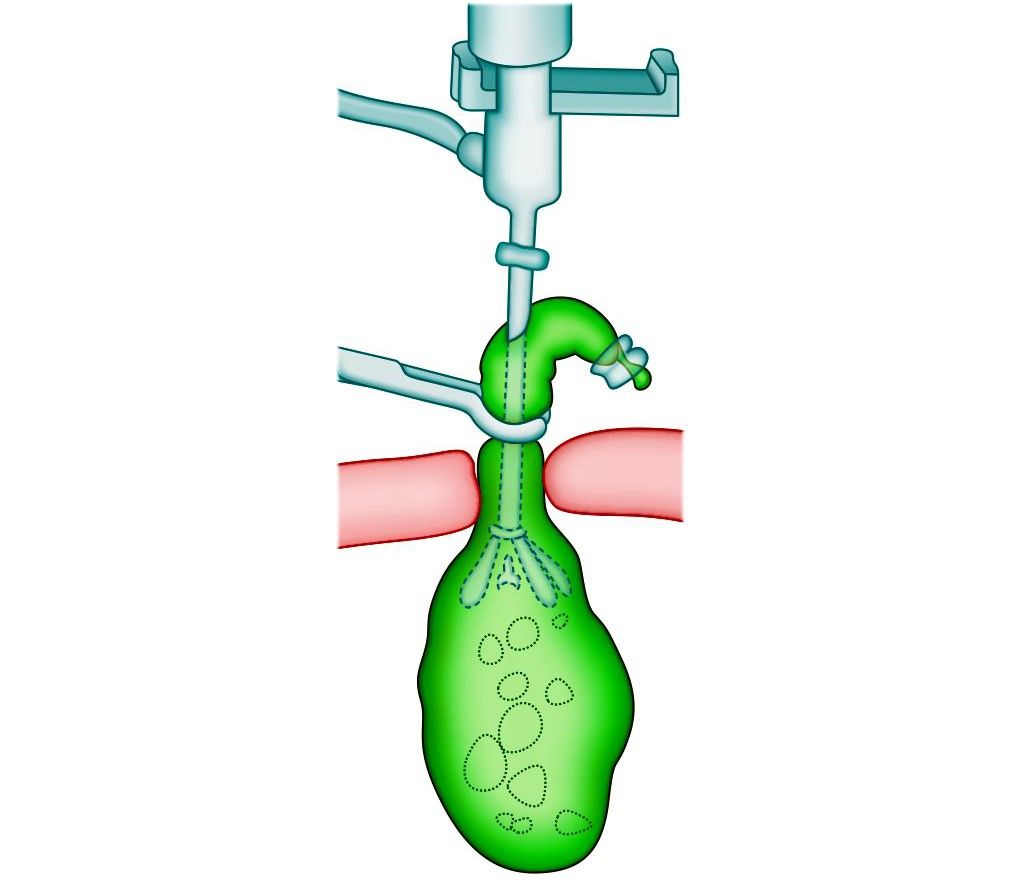

In many institutions, routine intraoperative cholangiogram is performed. Routine cholangiogram decreases the risk of CBD injury in case of difficult anatomy. If a cholangiogram is to be performed, the cystic duct is isolated and occluded with a clip that is placed high on the duct at its junction with the gallbladder. This will avoid leakage of contents from the gallbladder when the duct is opened. The scissors are used to incise the duct.

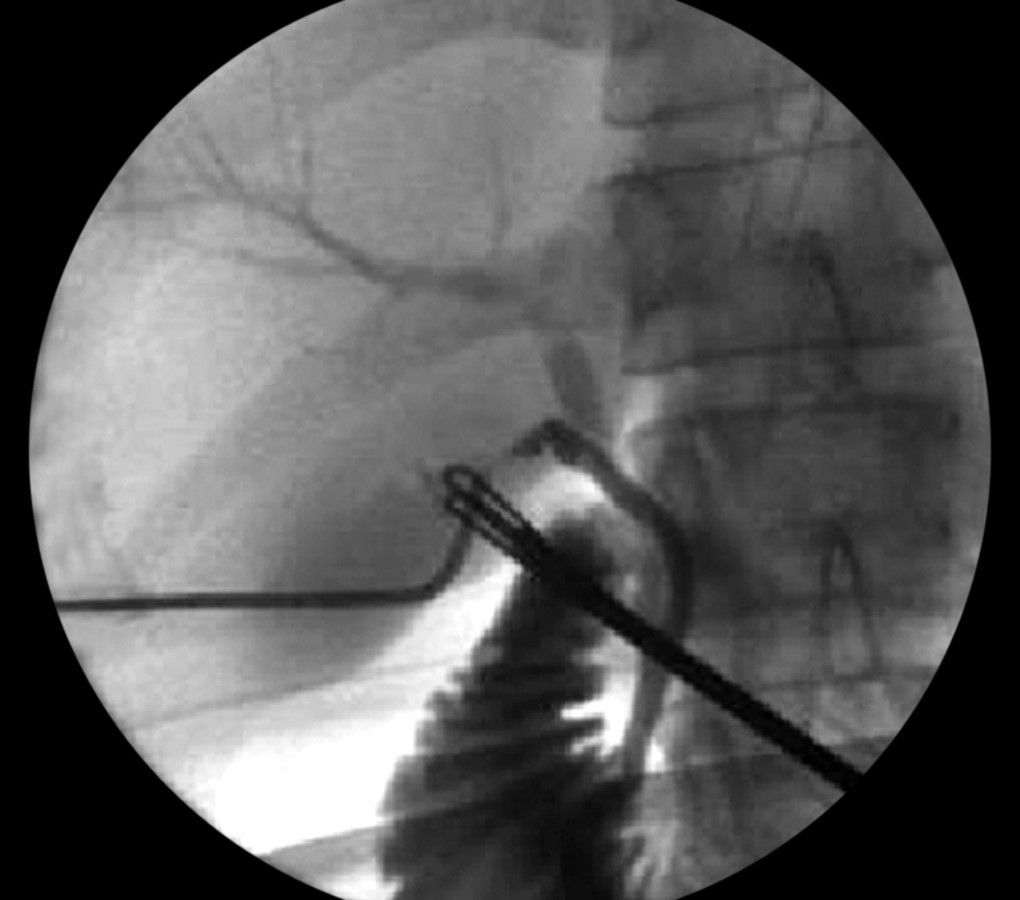

Intraoperative cholangiogram

The opening in the cystic duct is made on the anterosuperior aspect. Correct alignment of the cystic duct and infusion of saline facilitates the insertion of a ureteric catheter to perform cholangiography. Insertion is difficult if the opening in the cystic duct is made too close to the gallbladder. The dissector is used to spread the incision to adequately dilate it for introduction of the cholangiogram catheter. The catheter is introduced through one of the 5 mm port. It is secured by either inflating a balloon or placing a clip to hold it in place. The catheter is then flushed with saline to ensure appropriate placement. All instruments are removed and a dynamic cholangiogram with real-time fluoroscopy is performed. The contrast medium should be injected slowly during screening and the patient should be in a slight Trendelenburg’s position with the table rotated slightly to the right. It is essential that the entire biliary tract is outlined. When the cholangiogram is completed, the catheter is removed, and two clips are placed proximally on the duct. The duct is then divided. The surgeon should ligate or clip cystic duct when he is sure up to the point of absolute certainness.

The main advantages of intraoperative cholangiography during cholecystectomy are:

• Detection of common bile duct stone

• Reduction of the incidence of residual common bile duct stone

• Delineation of the biliary anatomical variations at risk for bile duct injury.

An intraoperative cholangiogram is a highly sensitive tool for detecting choledocholithiasis, with an overall accuracy of 95 percent. Routine intraoperative cholangiography can diagnose unsuspected common bile duct stone in 1 to 14 percent (average 5%) of patients without indications for ductal exploration.

The failure of laparoscopic intraoperative cholangiogram is due to:

• The narrowness of the cystic duct

• Cystic duct rupture

• Obstructive cystic valves

• Impacted cystic stones

• Dye extravasation from cystic duct perforation.

With increased experience, successful laparoscopic intraoperative cholangiogram can be achieved in 90 to 99 percent of cases, a rate similar to that of intraoperative cholangiogram during open cholecystectomy.

Intraoperative Ultrasonography

Many studies focused on the role of intraoperative ultrasonography in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Intraoperative ultrasonography is technically demanding but is as accurate as intraoperative cholangiogram (88–100%) for screening common bile duct stone.

The advantages of intraoperative ultrasonography over intraoperative cholangiogram are:

• Speedy

• Safer

• Multiple time use

• Economical.

The greater sensitivity of intraoperative ultrasonography examination concerned mainly small stones or debris in the CBD.

The disadvantages of intraoperative ultrasonography is that it is impossible to provide extended views of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree, difficult to show the passage of contrast into the duodenum and to identify bile duct injuries.

Ligation of Cystic Duct

Although the majority of surgeons opt for clipping the cystic duct, before dividing it, this technique though quick, is intrinsically unsound, as an internalization of the metal clip inside the common bile duct over the ensuing months is well documented. There is a report of internalization of the clip and subsequent stone formation after many years. The internalized clip becomes covered with calcium bilirubin pigment. For this reason, to tie the cystic duct using a catgut Roeder external slip knot should be done.

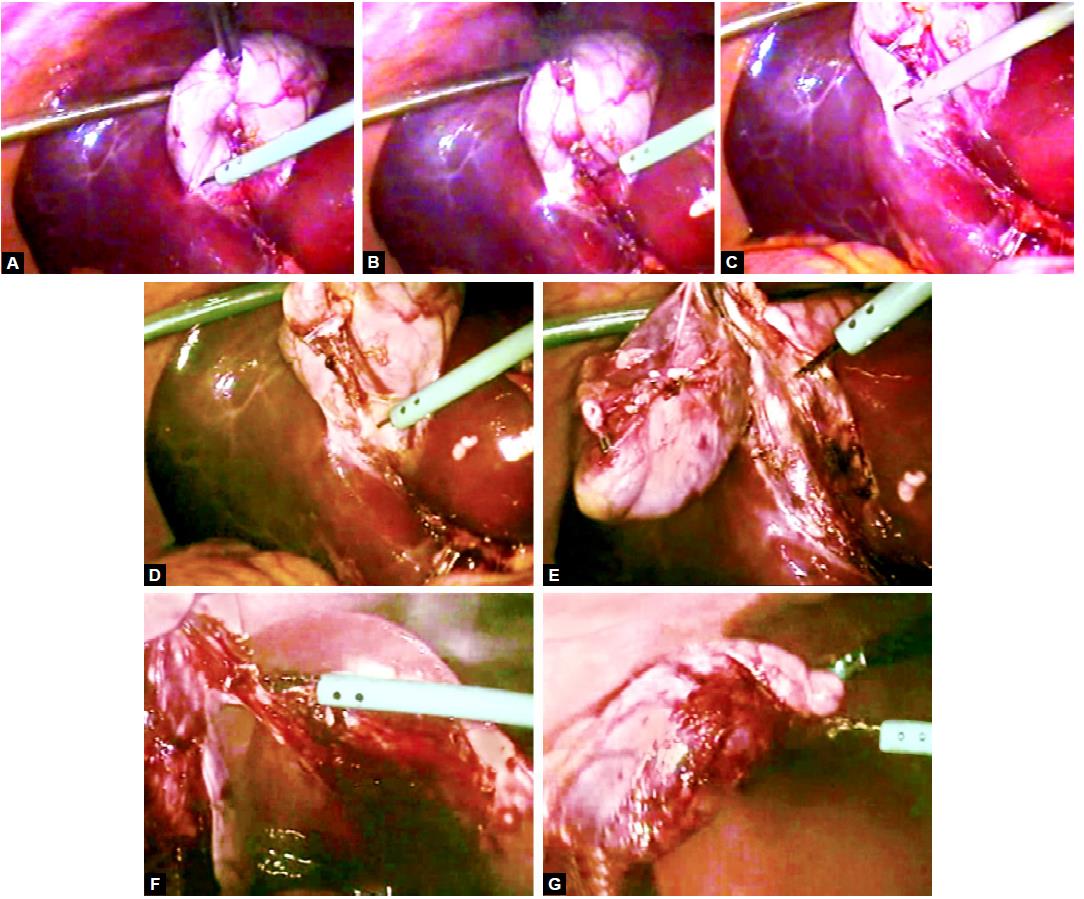

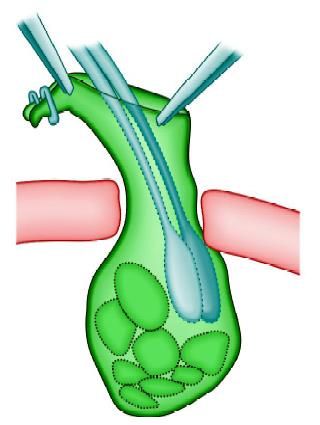

Dissection of Gallbladder from Liver Bed

The electrosurgical hook is used with cautery through the epigastric port to dissect the gallbladder from the bed of the liver. Using a grasper the gallbladder is first retracted right to expose and dissect the medial side of the attachment. The gallbladder is then retracted to the left and the lateral side is dissected. Using this back and forth action. The hook is used to dissect the gallbladder off the bed from inferior to superior until it is 90 percent removed from the liver. Holding the remaining portion of the gallbladder attached to the liver, the dissection bed, and the clipped structures are evaluated and any active bleeding is stopped using the heal of the hook or spatula.

Gallbladder should be separated from the liver through the areolar tissue plane binding the gallbladder to the Glisson's capsule lining the liver bed. The actual separation can be performed with scissors with electrosurgical attachment or electrosurgical hook knife. Pledget can be used to remove the gallbladder from the liver bed once a good plane of dissection is found. Perforation of the gallbladder during its separation is a common complication that is encountered in 15 percent of cases. One should be careful at the time of dissection and if there is spillage of stone, each stone should be removed from the peritoneal cavity to avoid abscess formation in the future.

Separation of gallbladder from gallbladder (GB) bed

Separation of the gallbladder from liver using hook

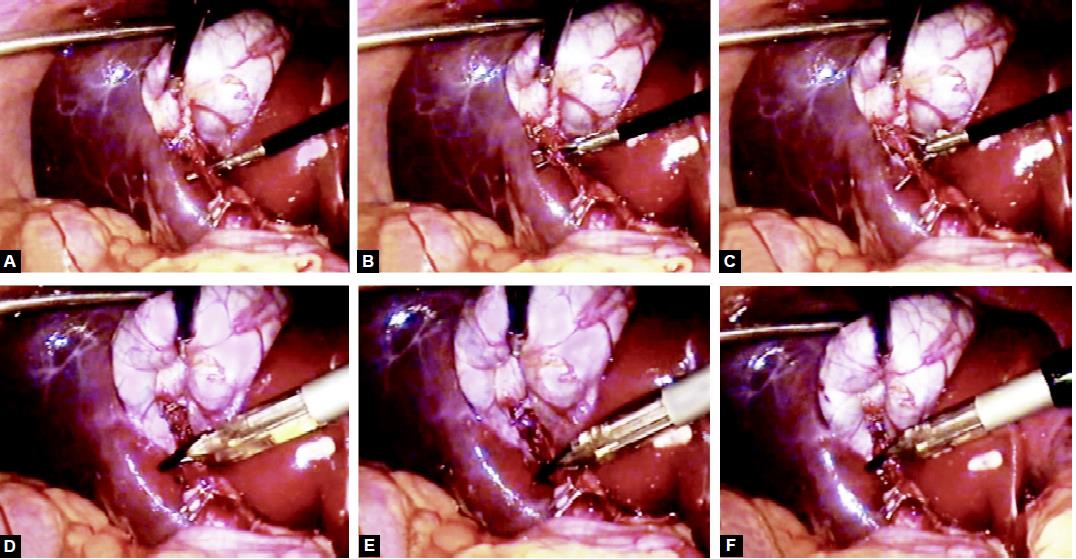

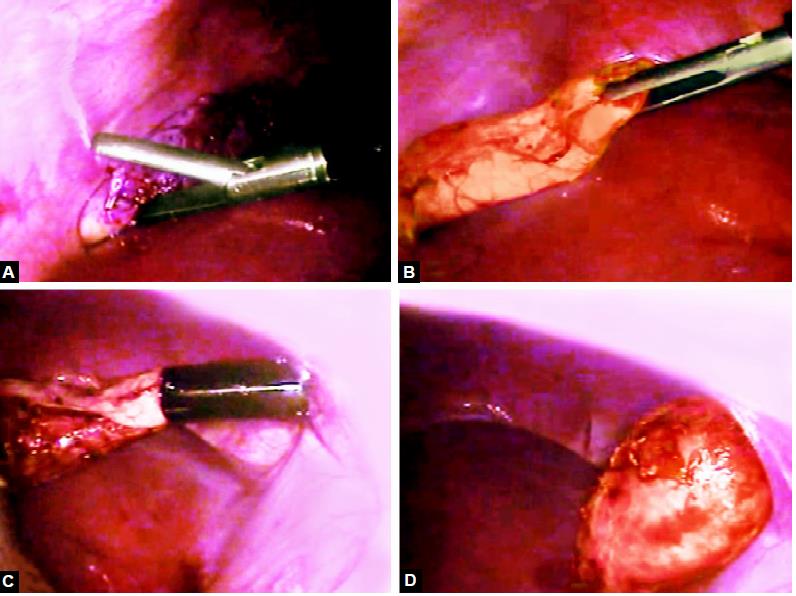

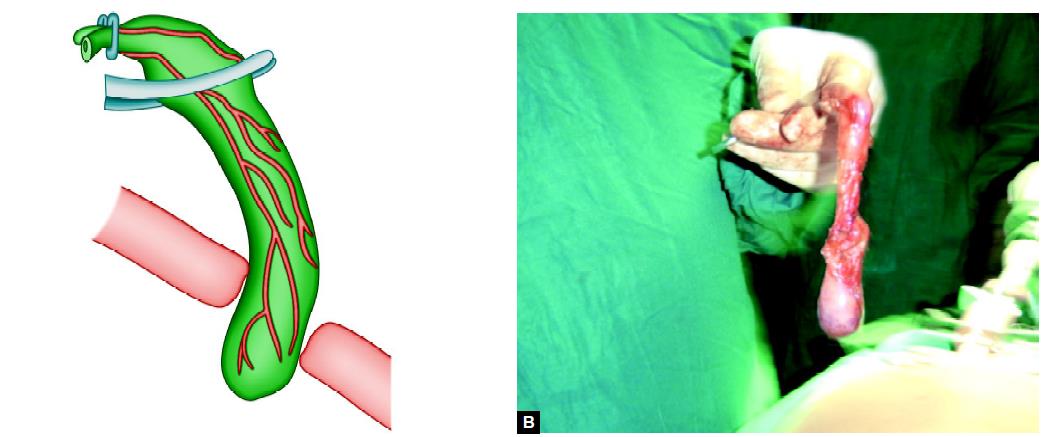

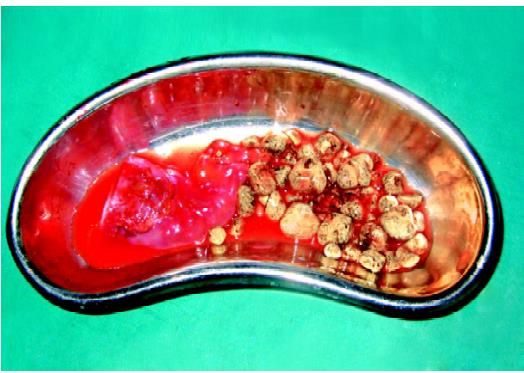

Extraction of Gallbladder

The gallbladder is now freed from the liver and placed on top of the liver. The patient is returned to the supine position and the area of dissection and the upper right quadrant are irrigated and suctioned until clear. The gallbladder is extracted through the 11 mm epigastric operating port with the help of a gallbladder extractor. Many surgeons use the umbilical port for withdrawal of gallbladder. If the gallbladder is removed through the umbilical port the laparoscope is placed through the epigastric port and the gallbladder is visualized on the dome of the liver. A large grasper with teeth is placed through the umbilical port and used to grasp the gallbladder along the edge of the clipped cystic duct stump. The gallbladder is then exteriorized through the umbilical incision where it is held into position with a clamp. First, the neck of the gallbladder should be engaged in the cannula, and then cannula will withdraw together with the neck of gallbladder held within the jaw of gallbladder extractor.

Once the port with the neck of the gallbladder is out, the neck is grasped with the help of a blunt hemostat and it should be pulled out with screwing. If the gallbladder is of small size, it will come without much difficulty, the otherwise small incision should be given over the neck of the gallbladder and suction irrigation instrument should be used to suck all the bile to facilitate easy withdrawal.

Extraction of gallbladder

Extraction of the gallbladder by a gentle push from outside

Extraction of the gallbladder by hiding the neck in the cannula

The suction of bile to extract gallbladder

The stone should be taken out to reduce the volume of the gallbladder

Sometimes big stones will not allow easy passage of gallbladder and in these situations, ovum forceps should be inserted inside the lumen of gallbladder through the incision of its neck and all the stone should be crushed. When ovum forceps is used to remove the big stones from the gallbladder, care should be taken that gallbladder should be held loose to have room for forceps otherwise it will perforate and all the stone may spill out. Extraction inside a bag is recommended as a safeguard against stone loss and contamination of the exit wound.

Stone may be crushed to reduce the volume of the gallbladder

Once the gallbladder is an empty gentle pull from outside will facilitate its extraction

The spilled stone and torn gallbladder can be taken out with the help of endobag

The spilled stone and torn gallbladder can be taken out with the help of endobag

Ending of the Operation

The instrument and then ports are removed. The telescope should be removed leaving the gas valve of umbilical port open to let out all the gas. At the time of removing the umbilical port, the telescope should be again inserted and the umbilical port should be removed over the telescope to prevent any entrapment of omentum. The wound is then closed with suture. Vicryl should be used for rectus and unabsorbable intradermal or stapler for the skin. A single suture is used to close the umbilicus and upper midline fascial opening. Many laparoscopic surgeons routinely leave this fascial defect without ill defect. Some surgeons like to inject local anesthetic agents over port sites to avoid postoperative pain. Sterile dressing over the wound should be applied.