Critical View Of Safety Technique During Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy In Prevention Of Biliary Injuries

"CRITICAL VIEW OF SAFETY TECHNIQUE DURING LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLECYSTECTOMY IN PREVENTION OF BILIARY INJURIES”

DR.VIVEK VISWANATHAN DEPARTMENT OF SURGERY INDRAPRASTHA APOLLO HOSPITAL NEW DELHI

PROTOCOL FOR THE SUBMISSION OF THESIS FOR THE AWARD OF DEGREE OF MASTER OF MINIMAL ACCESS SURGERY

SESSION: 2014-2015

TITLE OF THESIS : ‘’ CRITICAL VIEW OF SAFETYTECHNIQUEDURING LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLOECYSTECTOMY IN PREVENTION OF BILIARY INJURIES.’’

NAME OF CANDIDATE : DR. VIVEK VISWANATHAN M.S (General Surgery) F.MAS, D.MAS, FICRS

NAME OF GUIDE : DR. H. P. GARG (Sr. Consultant, General and Laparoscopic Surgery, Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, New Delhi)

NAME OF CO-GUIDE : DR. R. K MISHRA (Sr. Consultant, General, Laparoscopic& Robotic Surgery, World Laparoscopy Hospital, Gurgaon)

VENUE OF STUDY : Indraprastha Apollohospital, New Delhi

Acknowledgment

First and foremost, I offer my sincerest gratitude to my Teacher and mentor for this dissertation topic, Dr.H.P Garg, Senior Consultant General, Laparoscopic and Bariatric Surgery; Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, for his supervision, advice and guidance from the very early stage of this research as well as giving me extraordinary experiences and unflinching encouragement throughout the work. It has been an honour to be his student, for teaching me, both consciously and unconsciously; the rigors and the skills required in the field of Minimal Access Surgery and most importantly imbibing in me the work ethics required to become a better minimal access surgeon.

With regards to this opportunity, I would like to give special thanks to Dr. Sunil Kaul, Senior Consultant General, Laparoscopic and Robotic Surgery; Apollo Hospital, Dr R.K Mishra, Director of World Laparoscopy Hospital and Dr J.S Chowhan, for their invaluable suggestions and inspirations to make this study successful.

I wish to thank all Consultants and staff members of Department of Surgery at Apollo Hospital, for their kind guidance and help which has been a very productive and stimulating experience. My colleagues, seniors as well as juniors, have contributed immensely to my study. The camaraderie that we shared was one of the important sources of advice and collaboration and I wish my sincerest thanks to them. I am heavily indebted to all my patients who are the backbone of this study and have given me their unconditional support.

I thank God, without whose grace my existence is not possible. My special thanks to my family and friends for all their love and encouragement, without whom it would have been impossible for me to come so far.

Finally, I would like to thank everyone who was so important to the successful realization of this dissertation study, as well as expressing my apology that I could not mention everyone personally, one by one.

Dr.Vivek Viswanathan

M.S, F.MAS, D.MAS, FICRS

CONTENTS

2. AIMS & OBJECTIVES :

Inclusion criteria:

1. Nil by mouth 8 hour prior to surgery

2. I.V. fluid monitored by urine out put

3. Pre-anaesthetic checkup

4. Physician clearance

Key Steps Of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy:

Operative Techniquesused In This Study :

The 2 groups had a homogeneous case mix between cholelithiasis, chronic cholecystitis, and acute cholecystitis, as presented in Table 1.

No significant differences were found regarding age, sex, ASA risk, obesity, or previous operations between the 2 cohorts of patients.

Patients with associated pathologies or adhesions that could complicate the operation were excluded. Also converted cases ( 5% of the total and equally distributed) were excluded.

Operative technique was standard in both CVS and infundibular (IN) approaches, and the trocar position resembled the 4-port French scheme.

In the CVS technique, cephalad traction of the fundus is obtained by the grasper, together with a lateral traction of the infundibulum by the grasper.

A complete incision of the serosa is performed both in the medial and lateral aspect of the infundibulum and extended upwards almost to the fundus.

The medial incision is performed over the vertical fatty line visible on the gallbladder wall; it usually corresponds to the anterior cystic artery.

The medial release of the artery is obtained with electrocautery by dissecting it from the gallbladder wall. The section of Calot’s artery (which connects the cystic artery to the cystic duct) permits access to the critical safety triangle, set between the gallbladder wall on the right, the cystic duct inferiorly, and the cystic artery on the left.

The entire fatty dissection of this triangle and the mobilization of the infundibulum, both anteriorly and posteriorly, permits visualization of the liver surface through the triangle, well above Ruviers’ sulcus, as described by Strasberg et al.

The clipping and the section of the duct, next to the gallbladder, the clipping of the artery, and the retrograde dissection of the gallbladder complete the operation.

In the IN technique after suspension of the IV hepatic segment with a hanger and the lateral traction of the infundibulum , the serosa is incised parallel to the cystic duct and artery, just caudally to the infundibulum edge, thus dissecting the duct and artery to open Calot’s triangle.

After the identification of the 2 structures, passing through a fatty- free triangle, they are sectioned between clips, and retrograde cholecystectomy is completed. All patients were started oral intake on day 1, and generally were given discharge on the second postoperative day.

Statistical Analysis:

The Student t test was used to determine statistical significance in univariate analysis; power sample size was not calculated in order to obtain significance of mortality or bile injury outcomes (expected rate 0.4%), for which large prospective cohorts would have been needed.

Attention was focused instead on the operating time, as an indirect measure of “ease and confidence” with an operative technique to be recommended as the ideal approach for training purposes.

4. REVIEW OF LITERATURE :

The introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy was associated with a sharp rise in the incidence of biliary injuries:

1. Despite the advancement of laparoscopic cholecystectomy techniques, biliary injury continues to be an important problem today, although its true incidence is unknown. The most common cause of serious biliary injury is misidentification. Usually, the common bile duct is mistaken to be the cystic duct and, less commonly, an aberrant duct is misidentified as the cystic duct.

2. The former was referred to as the “classical injury” by Davidoff3and colleagues, who described the usual pattern of evolution of the injury at laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

3. In 1995, Strasberg and his colleagues authored an analytical review of this subject and introduced a method of identification of the cystic structures referred to as the “critical view of safety” (CVS).4(This approach to ductal identification had been described in 1992,but the term critical view of safety was used first in the 1995 article.)

During the past 15 years, this method has been adopted increasingly by surgeons around the world for performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Rationale of the CVS

The CVS has 3 requirements.

The rationale of CVS is based on a 2-step method for ductal identification that was and continues to be used in open cholecystectomy.

First, by dissection in the triangle of Calot, the cystic duct and artery are putatively identified and looped with ligatures.

Next, the gallbladder is completely dissected off the cystic plate, demonstrating that the 2 structures are the only structures still attached to the gallbladder.

Incorporation of the freeing of the gallbladder off the cystic plate so that the gallbladder is hanging from the cystic duct and artery is superior to simply demonstrating that 2 structures are entering the gallbladder because it shows that 2 and only 2 structures are attached to the gallbladder.

During early experiences with laparoscopic cholecystectomy, attempts were made to replicate the open approach laparoscopically.However, considerable difficulties were encountered.

First, it was more difficult laparoscopically to take the gallbladder off the cystic plate completely without first dividing the cystic duct and artery than it was with the open technique.

Another problem was the gallbladder tended to twist on the cystic structures after it was freed from its attachments to the liver, resulting in greater difficulty in clipping and dividing the cystic artery and duct.

In the course of these laparoscopic attempts to mimic the open method, it was realized that the same fidelity of identification obtained by taking the gallbladder off the cystic plate completely could be achieved by clearing only the lower part of the gallbladder off the plate, leaving the upper part of the gallbladder attached.

In addition, the twisting problem, which occurred when the gallbladder was detached completely, was not present when the fundus of the gall bladder remained attached to the liver.

At that point, the question became what was the least amount of gallbladder that must be separated from the cystic plate to achieve the fidelity of identification attained when the whole gallbladder is removed.

Logically, the amount is that which allows the surgeon to conclude that the gallbladder is being dissected off the cystic plate itself and not just being separated from attachments within the triangle of Calot.

The cystic plate, being made of fibrous tissue, usually has a dull white appearance.Occasionally, it is thin and translucent, allowing the underlying liver to be seen through it.

In cases with mild inflammation and areolar dissection planes, only a centimeter or so of the cystic plate needs to be cleaned free of gallbladder attachments to ensure that dissection is actually on the fibrous plate.

When there is greater inflammation that distance can be greater because fibrotic chronically inflamed tissues within the triangle of Calot can also have the same dull white color as the cystic plate.

The extent of dissection has to be that which results in the method being an adequate surrogate to dissecting the gallbladder off the liver bed entirely. Therefore, distance dissected needs to be that which makes it obvious that the only step left in the dissection—if the cystic structures were to be divided— would be removal of the remaining attachments of the gallbladder to the liver.

The making of 2 “windows” alone does not satisfy the requirements of CVS. To do so, enough of the gallbladder should be taken off the cystic plate so that it is obvious that the only step left after division of the cystic structures will be removal of the rest of the gallbladder off the cystic plate.

Also, although the common duct does not have to be seen, all fat and fibrous tissue must be removed from the triangle of Calot so that there is a 360-degree view around the cystic duct and artery, ie, the CVS should be apparent from both the anterior and posterior (reverse Calot) viewpoints.

Use of the CVS technique:

Standard procedure—mild and moderate inflammation present

The initial steps in performance of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy are similar in most methods.

A pneumoperitoneum is created, ports are inserted under direct vision, and graspers are placed on the gallbladder for retraction. The next step is to clear the triangle of Calot of fat and fibrous tissue.

This can be done with a variety of techniques, which include teasing tissue away with graspers or gauze dissectors, elevating and dividing tissue with hook cautery, and spreading tissue with blunt or curved dissecting instruments.

The dissection is commonly performed from the front and the back of the triangle of Calot.

Two points of safety for cautery are that it should be used on low power settings, typically 30 W and that any tissue to be cauterized should be elevated off surrounding tissue so that there is no unintentional arcing injury to surrounding structures.

Cautery should be applied in short bursts of 2 to 3 seconds or less to minimize thermal spread to surrounding structures.

Also, it is important that only small pieces of tissue be divided at one time because important biliary structures can be quite small in diameter.

Once this is done, there will be 2 and only 2 structures attached to the gallbladder and they can be visualized circumferentially.

At this point, the CVS has been achieved and the cystic structures can be divided.

If any doubt exists, as can occur when inflammation is severe, then more of the gallbladder should be taken off the cystic plate, including right up to the fundus, if necessary.

The CVS is not a dissection technique, but rather a technique of identification.

Affirmation of the CVS should take place at a pause in the operation and should be treated like a second timeout. The critical view should be demonstrated and ideally the surgeon and physician assistant, if present, should agree that it is achieved.

CVS in severe inflammation :

Surgeons are more likely to dissect the common bile duct circumferentially and believe it is the cystic duct in the presence of severe acute and chronic inflammation.

This occurs because certain factors present under these circum- stances tend to hide the cystic duct and fuse the common hepatic duct to the side of the gallbladder.

It is clear from operative notes that such circumstances can result in a compelling deception that the common duct is the cystic duct. The result in many cases has been bile duct injury.

If the surgeon is using a method, such as the infundibular view technique, and has come around the common bile duct thinking that it is the cystic duct, a 360-degree view of a funnel-shaped structure resembling the union of cystic duct and gallbladder can be obtained.

As this funnel shape is the requirement for identification by this method (infundibulum = funnel), the common bile duct will often be clipped and divided.

The common bile duct can be similarly dissected in error when using the critical view technique, but it will not be divided at this point because the other conditions for the CVS have not been met. The cystic artery has not been identified, the triangle of Calot has not been completely cleared, and the base of the cystic plate has not been displayed.

Under the same inflammatory conditions that lead to biliary injury in the infundibular view technique, the surgeon using the CVS will have difficulty proceeding after isolation of the common bile duct. This is actually desirable and should suggest that there is a problem.

It is important that the surgeon recognizes when this step in the operation becomes very difficult because it suggests there is a problem and additional attempts to attain CVS laparoscopically should be halted. Options include intraoperative cholangiography, conversion to open cholecystectomy, or soliciting the help of a colleague.

Stated otherwise, the critical view method is superior to the infundibular technique under conditions of severe inflammation because it is more rigorous.

The patient is protected precisely because the surgeon cannot usually achieve a misleading view. However, although CVS will usually protect against making incorrect identification, it will not protect against direct injury to structures by persistent dissection in the face of highly adverse local conditions.

Evidences that CVS prevents biliary injuries :

1) Yegiyants and colleagues reported on 3,042 patients who had laparoscopic cholecystectomy using CVS for identification in the period 2002-2006.The study was limited because data were obtained from an administrative database and CVS was not used in all laparoscopic cholecystectomies.

One bile duct injury occurred in an 80-year-old patient with severe inflammation. The injury occurred during dissection before the CVS was achieved, ie, none of 3,042 patients having laparoscopic cholecystectomy had an injury because of misidentification.

The expected rate of injury was between 2 and 4 per 1,000 cholecystectomies and most would be expected to result from misidentification. The actual rate of injury was much lower than the expected rate.

2) Avgerinos5 and colleagues reported on 1,046 patients having laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a single institution from 2002-2007.5 In 998 cases CVS was used. The conversion rate was 2.7%. There were 5 bile leaks, which resolved spontaneously. No major bile duct injuries occurred.

3) Heistermann6 and colleagues reported on 100 patients who had laparoscopic cholecystectomy using CVS.

The purpose of the study was to determine how often it was possible to attain CVS and demonstrate it with photo documentation. Despite a high incidence of acute cholecystitis and prior abdominal surgery, 97 of 100 cholecystectomies were completed laparoscopically after achieving photo documentation of CVS. There was 1 postoperative cystic duct stump leak.

4) Wauben7 and colleagues reported on use of ductal identification techniques in The Netherlands, including CVS.In this survey, it was found that Dutch surgeons used a variety of techniques for ductal identification, but few surgeons used CVS.

Subsequently, the Dutch Society of Surgery established a commission to study the problem of biliary injury in that country. The commission developed best practice guidelines for performing cholecystectomy and adopted CVS as the standard method of performing ductal identification.

Photo documentation of CVS before division of the cystic duct was recommended in these guidelines.

In summary, there is no Level I evidence that CVS reduces bile duct injury. To prove this claim would require a randomized trial.

The difficulty in performing such a trial can be illustrated as follows: even if there was a 4-fold increase in the incidence of biliary injury from 0.1% to 0.4% as a result of introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, it would be difficult to detect because a randomized trial would require 4,500 patients per arm to detect that difference at a 95% confidence level.

The logistics and cost of performing a surgical trial of this magnitude are overwhelming.

Probably the best that can be achieved is the all or none Level I type of evidence, in which it is shown that biliary injuries resulting from misidentification do not occur when a particular technique is used; from a practical perspective, that would be sufficient.

The case series of Yegiyants and colleagues8and Avgerinos and colleaguesapproach that standard. The results of the Dutch best practices initiative will be of great interest and might provide additional support for CVS if the policy is implemented successfully and if it results in a reduction in biliary injuries in The Netherlands.

PROFORMA

6. Study Proforma :

Clinical Details:

Symptoms :

Preoperative Investigations:

Surgery Details :

@24hrs:

@48hrs:

Problems Encountered During Surgery:

Extra analgesia required :- Dose: Days:

Follow Up :

7. RESULTS :

One hundred (100) patients underwent admission for cholecystitis.

The mean age of the study population was 36.50years, with therange of 10 to 60years in this study, the total number of male patients being 52(52%)while the number of female patients being 48(48%)with M:Fratio being 1.10 : 1.

Analysis ofage groups showed ahigh incidence ofacutecholecystitis among adults between 30-40years( 38%) . The highest prevalence of acute cholecystitisinmales was observed in the agegroup 31-40 years (47.5%)as also forfemales it was in in whom it was (33.33%).

The lowest prevalence ofacute cholecystitis inmales and female was inthose aged above 51 yrs (12%).

Table : Age And Sexwise Distribution Of Patients

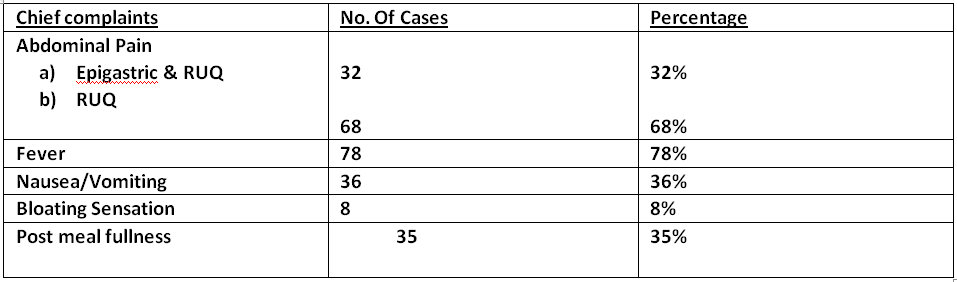

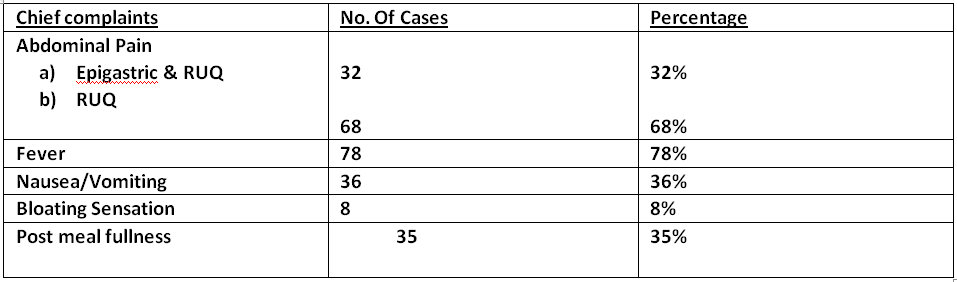

Chief Complaints

In our study abdominal pain was the main symptom followed by fever and then nausea/vomiting.

General Physical examination

Per Abdomen Examination

Laboratory Findings

Ultrasound findings

Operative Technique :

Table 1: Comparison between the two different techniques of laparoscopic cholecystectomy

No mortalities occurred in the series. Morbidity was 0.1% (1 patient) in group 1 and 0.2% in group 2 (2 patients).

One biliary leak from the cystic duct in the first patient (acute gangrenous cholecystitis) resolved after an endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed on postoperative day 1.

The other 2 patients had intraoperative hemorrhages, both controlled with bipolar coagulations and clip applications; 1 of the 2 patients required blood transfusions.

No difference was found regarding pain, wound infections, time to first passage of stool, re-feeding, or discharge.

Neither group required the use of high-tech instruments (Harmonic or radiofrequency devices) apart from mono- or bipolar cautery.

Cholangiography has never been performed intraoperatively.

Significant differences were found in the operative times. Both median times (51.5 min vs 69.7 min) and average time divided by case-difficulty (defined by different grades of gallbladder inflammation) were in favor of the CVS approach. The difference was minor (but still significant) for acute cholecystitis (Table 2).

Table 2 : Comparison between the operative times in both groups

Histopathology revealed acute cholecystitis in 37 cases and chronic cholecystitis in 22 cases. For the rest of patients histopathology was suggestive of acute onchronic cholecystitis.

8. DISCUSSION:

Figure 1: The “critical view of safety.” as shown by Strasberg9 The triangle of Calot is dissected free of all tissue except for cystic duct and artery, and the base of the liver bed is exposed. When this view is achieved, the two structures entering the gallbladder can only be the cystic duct and artery. It is not necessary to see the common bile duct.

Prevention of iatrogenic bile injuries is still a matter of significant concern, despite almost 25 years passing since the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed.

The debate has sparked renewed interest since the introduction of natural orifice surgery (NOTES)10and single port access surgery11.

In Italy, a national survey shows an incidence of 0.42% of major bile injuries during LC in 56 591 patients, with higher rates in cholecystitis and low-volume practice subgroups.12

The approach to the gallbladder’s pedicle is of utmost importance for the prevention of injuries. Three main techniques have been standardized.

The oldest and most common approach is the infundibular one. The classic dissection of Calot’s triangle might misrepresent vascular or biliary anatomical variants, which are frequently located in the medial part of the area. 13

Strasberg identified an “error trap” 14to avoid, regarding the IN technique, in which the common hepatic duct might be mistaken for the gallbladder wall in severe inflammation.

Katkhouda et al15 suggest the extension of the cystic duct’s dissection to the confluence with the common hepatic duct, to perform what he calls a “visual cholangiography.”

Another way to prevent injuries, more frequently performed in open surgery (but also described in LC, mostly with the use of ultrasonic sharp dissection16), is the “dome-down” or “fundus-first” technique, often advocated for acute cholecystitis.16

The error trap of this technique (following Strasberg) concerns the possible injury to the right hepatic artery, which might be retracted downwards, along with the gallbladder.17

Routine intraoperativecholangiography has been advocated by many authors:18 its use, especially in emergencies, calls for some organization in the operating theater and operative expertise. Alas, intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) does not seem to prevent bile duct injuries, even if it helps with immediate identification of the injury.19

IOC ineffectiveness at lowering the rate of biliary lesions has been confirmed in large multicenter trials. There was no need, in either of our groups, for intraoperative cholangiograms, which are not routinely performed in our patients.

The importance of cholangiography in clarifying unclear anatomy is ascertained, but largely unnecessary in our opinion, both for the rate of failure of cystic duct cannulation and for the possible injuries that may be caused by the incautious forcing of the biliary catheter through the cystic valve, especially in inflammatory entanglement of the duct.

The effort to standardize an approach to the cystic artery and duct that could effectively avoid the area where ductal and arterial anomalies are likely to be encountered brought Strasberg et al to outline the “critical view of safety.” Since 1995, their suggestion has been little mentioned, until the initial papers and retrospective series started analyzing the results of the technique.20,

After these studies, other authors21from around the world have started collecting cases and standardizing the operative technique. The results seem promising, as in large single- institution series, the “observed BDI rate drops from 1/9 to 1/15, representing an order-of-magnitude of improvement in the safety of LC”: the authors consider these results as superior to routine cholangiography.22

Other authorshave tested the validity of the technique even in acute cholecystitis (performed by entering the inner subserosal layer for dissection). The approach is considered viable even for NOTES gallbladder surgery. 23

A safe cholecystectomy technique is particularly important when considering trainees or young surgeons, who have scarce experience in biliary anatomical variance and are at risk of causing a major injury under emergency conditions (intraoperative bleedings, difficult anatomy, severe inflammation).24

9. CONCLUSIONS :

Our results show no difference in terms of complications between an experienced laparoscopic surgeon using the In fundibular approach or the CVS; a minor number of intraoperative bleedings, without statistical significance, could validate the rationale of the CVS approach towards dissection of an area without vascular abnormalities; moreover, the distal clipping of the cystic artery may favor easier dissection and consequently fewer accidental bleedings, especially in inflammatory conditions.

The power of our study is not sufficient to analyze the outcome of the “bile duct injury rate,” as multicenter trials are required because of the low expected rate of events.

The shorter operative times are symptomatic of increased confidence due to the technique, which probably makes the surgeon feel more secure, both with inflamed and uninflamed anatomy.

We believe that a diffusion of this simple, practical technique might be desirable in training hospitals, residencies, and district hospitals, or anywhere laparoscopic experience might be basic or limited to standard operations.25

The results of CVS in the literature and in the present study forecast the approach as the future gold standard in the dissection of the gallbladder elements, and a further dissemination of the technique is important, especially for training purposes.

10. BIBLIOGRAPHY :

1. A prospective analysis of 1518 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. The Southern Surgeons Club. N Engl J Med 1991;324: 1073–1078.

2. StrasbergSM,HertlM,SoperNJ.Ananalysisofthe problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am CollSurg 1995;180:101–125.

3. Davidoff AM, Pappas TN, Murray EA, et al. Mechanisms of major biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 1992;215:196–202.

4. Strasberg SM, Sanabria JR, Clavien PA. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Can J Surg 1992;35:275–280.

5. AvgerinosC,KelgiorgiD,TouloumisZ,etal.Onethousand laparoscopic cholecystectomies in a single surgical unit using the “critical view of safety” technique. J GastrointestSurg 2009;13:498–

503.

6. HeistermannHP,TobuschA,PalmesD. [Preventionofbileduct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. “The critical view of safety”]. Zentralblatt fur Chirurgie 2006;131:460–465.

7.Wauben LS, Goossens RH, van Eijk DJ, et al. Evaluation of protocol uniformity concerning laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the Netherlands. World J Surg 2008;32:613–620.1. Cuschieri A, Terblanche J. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: evolution, not revolution. Surg Endosc. 1990;4:125-126.

8.YegiyantsS,CollinsJC,YegiyantsS,CollinsJC.Operative strategy can reduce the incidence of major bile duct injury in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am Surg 2008;74:985-957.

9.Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. Isolation of right main and right sectional portal pedicles for liver resection with- out hepatotomy or inflow occlusion. J Am CollSurg 2008;206: 390–396.

10. AuyangED,HungnessES,VaziriK,etal.Naturalorifice translumenal endoscopic surgery (NOTES): dissection for the critical view of safety during transcolonic cholecystectomy. SurgEndosc

2009;23:1117–1118.

11.Hodgett SE, Matthews BD, Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. Single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC): initial experience with critical view dissection and routine intraoperative cholangiography. SurgEndosc 2009;23:S332

12. Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Giovannini I, Ardito F, D’Acapito F, Vellone M, Murazio M, Capelli G. Bile duct injury during lapa- roscopic cholecystectomy. Results of an Italian national survey on 56591 cholecystectomies. Arch Surg. 2005;140:986-992.

13. Strasberg SM, Eagon CJ, Drebin JA. The “hidden cystic duct&rd

DR.VIVEK VISWANATHAN DEPARTMENT OF SURGERY INDRAPRASTHA APOLLO HOSPITAL NEW DELHI

PROTOCOL FOR THE SUBMISSION OF THESIS FOR THE AWARD OF DEGREE OF MASTER OF MINIMAL ACCESS SURGERY

SESSION: 2014-2015

TITLE OF THESIS : ‘’ CRITICAL VIEW OF SAFETYTECHNIQUEDURING LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLOECYSTECTOMY IN PREVENTION OF BILIARY INJURIES.’’

NAME OF CANDIDATE : DR. VIVEK VISWANATHAN M.S (General Surgery) F.MAS, D.MAS, FICRS

NAME OF GUIDE : DR. H. P. GARG (Sr. Consultant, General and Laparoscopic Surgery, Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, New Delhi)

NAME OF CO-GUIDE : DR. R. K MISHRA (Sr. Consultant, General, Laparoscopic& Robotic Surgery, World Laparoscopy Hospital, Gurgaon)

VENUE OF STUDY : Indraprastha Apollohospital, New Delhi

Acknowledgment

First and foremost, I offer my sincerest gratitude to my Teacher and mentor for this dissertation topic, Dr.H.P Garg, Senior Consultant General, Laparoscopic and Bariatric Surgery; Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, for his supervision, advice and guidance from the very early stage of this research as well as giving me extraordinary experiences and unflinching encouragement throughout the work. It has been an honour to be his student, for teaching me, both consciously and unconsciously; the rigors and the skills required in the field of Minimal Access Surgery and most importantly imbibing in me the work ethics required to become a better minimal access surgeon.

With regards to this opportunity, I would like to give special thanks to Dr. Sunil Kaul, Senior Consultant General, Laparoscopic and Robotic Surgery; Apollo Hospital, Dr R.K Mishra, Director of World Laparoscopy Hospital and Dr J.S Chowhan, for their invaluable suggestions and inspirations to make this study successful.

I wish to thank all Consultants and staff members of Department of Surgery at Apollo Hospital, for their kind guidance and help which has been a very productive and stimulating experience. My colleagues, seniors as well as juniors, have contributed immensely to my study. The camaraderie that we shared was one of the important sources of advice and collaboration and I wish my sincerest thanks to them. I am heavily indebted to all my patients who are the backbone of this study and have given me their unconditional support.

I thank God, without whose grace my existence is not possible. My special thanks to my family and friends for all their love and encouragement, without whom it would have been impossible for me to come so far.

Finally, I would like to thank everyone who was so important to the successful realization of this dissertation study, as well as expressing my apology that I could not mention everyone personally, one by one.

Dr.Vivek Viswanathan

M.S, F.MAS, D.MAS, FICRS

CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

- MATERIALS AND METHODS

- REVIEW OF LITERATURE

- PROFORMA

- RESULTS

- DISCUSSION

- CONCLUSION

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Sir Alfred Cuschieri, in an editorial released in 1990,cheered the first steps in laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) as the beginning of a new, exciting era, but alerted surgeons to be cautious, in order to avoid a substantial surgically induced morbidity.

- Twenty years later, the small increase in the rate of iatrogenic major biliary injury is tolerated, thanks to the great benefits of this minimally invasive approach. Indeed biliary morbidity with LC is not less than the 0.4% rate of traditional open surgery, but almost 3 times higher.1

- Nonetheless, the National Institutes of Health consensus elected LC as the “gold standard” for cholelithiasis in 1992.

- Strasberg et al,2in the early nineties, pointed out how a “critical view of safety” (CVS) should be achieved every time, by dissecting the entire infundibulum off the liver bed and by freeing it of all fatty tissue, both in its dorsal and ventral aspects. This, in his opinion, would have prevented accidental biliary and vascular injuries, due to uncommon variations, incautious bleeding control, or unclear anatomy.

- These principles have been ignored until recent years, when standardization of the technique, together with some consistent data, have appeared in the literature, asserting that this way of dissecting the gallbladder pedicle would bear a highly protective role against bile duct injuries. This would be especially important in teaching the approach to the gallbladder hilus.

- Wide exposure of adjoining body of Gall Bladder from liver bed will ensure prevention of CBD injury, as also exposure of the Calot’s triangle and cystic duct and cystic artery.Alongwith this thedissection and separationof adjoining body of gall bladder from liver bed will ensure prevention of CBD injury.

- The present study aims to evaluate the incidence of biliary injury when this technique is adopted.

2. AIMS & OBJECTIVES :

- To evaluate the incidence of biliary injuries following the critical view of safety technique and

- To compare with the incidence occurring during standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy as given in literature.

- Minimum 50 cases will be studied.

- It is a prospective study and will be done on all admitted patients at IAH, New Delhi.

- Patient will be included after their informed voluntary consent for the study.

- The Study Will Be Based On Patient Information Sheet As Described.

- Pain Score Will Be Analysed On The Basis Of Visual Analogue Scale.

- Four Port Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Will Be Done.

Inclusion criteria:

- All cases which are fit for laparoscopic cholecystectomy under general anaesthesia will be included.

- Only those cases where it is possibletechnically, to expose the critical view of safety before clipping and division of cystic duct will be included.

- On laparoscopy all those cases where it is not possible technically to dissect and expose the critical view of safety will be excluded from the study.

1. Nil by mouth 8 hour prior to surgery

2. I.V. fluid monitored by urine out put

3. Pre-anaesthetic checkup

4. Physician clearance

Key Steps Of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy:

- Step1 : Creation of pneumoperitoneum and insertion of trocars

- Step2 : Separating of adhesions towards the gall bladder and the surrounding liver, having exposure of the peritoneal fold in which cystic duct as well as artery are situated.

- Step3 : Dissection as well as skeletonisation from the cystic duct as well as cystic artery as well as occlusion and also the division of these structures

- Step4 : Dissection and extraction of the gall bladder and closure of incisions.

- Post-op analgesia

- Pain at 6 hour

- Pain at 24 hour

- Pain at 48 hour

- Hospital stay

- Follow up

Operative Techniquesused In This Study :

The 2 groups had a homogeneous case mix between cholelithiasis, chronic cholecystitis, and acute cholecystitis, as presented in Table 1.

No significant differences were found regarding age, sex, ASA risk, obesity, or previous operations between the 2 cohorts of patients.

Patients with associated pathologies or adhesions that could complicate the operation were excluded. Also converted cases ( 5% of the total and equally distributed) were excluded.

Operative technique was standard in both CVS and infundibular (IN) approaches, and the trocar position resembled the 4-port French scheme.

In the CVS technique, cephalad traction of the fundus is obtained by the grasper, together with a lateral traction of the infundibulum by the grasper.

A complete incision of the serosa is performed both in the medial and lateral aspect of the infundibulum and extended upwards almost to the fundus.

The medial incision is performed over the vertical fatty line visible on the gallbladder wall; it usually corresponds to the anterior cystic artery.

The medial release of the artery is obtained with electrocautery by dissecting it from the gallbladder wall. The section of Calot’s artery (which connects the cystic artery to the cystic duct) permits access to the critical safety triangle, set between the gallbladder wall on the right, the cystic duct inferiorly, and the cystic artery on the left.

The entire fatty dissection of this triangle and the mobilization of the infundibulum, both anteriorly and posteriorly, permits visualization of the liver surface through the triangle, well above Ruviers’ sulcus, as described by Strasberg et al.

The clipping and the section of the duct, next to the gallbladder, the clipping of the artery, and the retrograde dissection of the gallbladder complete the operation.

In the IN technique after suspension of the IV hepatic segment with a hanger and the lateral traction of the infundibulum , the serosa is incised parallel to the cystic duct and artery, just caudally to the infundibulum edge, thus dissecting the duct and artery to open Calot’s triangle.

After the identification of the 2 structures, passing through a fatty- free triangle, they are sectioned between clips, and retrograde cholecystectomy is completed. All patients were started oral intake on day 1, and generally were given discharge on the second postoperative day.

Statistical Analysis:

The Student t test was used to determine statistical significance in univariate analysis; power sample size was not calculated in order to obtain significance of mortality or bile injury outcomes (expected rate 0.4%), for which large prospective cohorts would have been needed.

Attention was focused instead on the operating time, as an indirect measure of “ease and confidence” with an operative technique to be recommended as the ideal approach for training purposes.

4. REVIEW OF LITERATURE :

The introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy was associated with a sharp rise in the incidence of biliary injuries:

1. Despite the advancement of laparoscopic cholecystectomy techniques, biliary injury continues to be an important problem today, although its true incidence is unknown. The most common cause of serious biliary injury is misidentification. Usually, the common bile duct is mistaken to be the cystic duct and, less commonly, an aberrant duct is misidentified as the cystic duct.

2. The former was referred to as the “classical injury” by Davidoff3and colleagues, who described the usual pattern of evolution of the injury at laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

3. In 1995, Strasberg and his colleagues authored an analytical review of this subject and introduced a method of identification of the cystic structures referred to as the “critical view of safety” (CVS).4(This approach to ductal identification had been described in 1992,but the term critical view of safety was used first in the 1995 article.)

During the past 15 years, this method has been adopted increasingly by surgeons around the world for performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Rationale of the CVS

The CVS has 3 requirements.

- First, the triangle of Calot must be cleared of fat and fibrous tissue. It does not require that the common bile duct be exposed.

- The second requirement is that the lowest part of the gallbladder be separated from the cystic plate, the flat fibrous surface to which the nonperitonealized side of the gallbladder is attached. The cystic plate, which is sometimes referred to as the liver bed of the gallbladder, is part of the plate/sheath system of the liver.

- The third requirement is that 2 structures, and only 2, should be seen entering the gallbladder. Once these 3 criteria have been fulfilled, CVS has been attained.

The rationale of CVS is based on a 2-step method for ductal identification that was and continues to be used in open cholecystectomy.

First, by dissection in the triangle of Calot, the cystic duct and artery are putatively identified and looped with ligatures.

Next, the gallbladder is completely dissected off the cystic plate, demonstrating that the 2 structures are the only structures still attached to the gallbladder.

Incorporation of the freeing of the gallbladder off the cystic plate so that the gallbladder is hanging from the cystic duct and artery is superior to simply demonstrating that 2 structures are entering the gallbladder because it shows that 2 and only 2 structures are attached to the gallbladder.

During early experiences with laparoscopic cholecystectomy, attempts were made to replicate the open approach laparoscopically.However, considerable difficulties were encountered.

First, it was more difficult laparoscopically to take the gallbladder off the cystic plate completely without first dividing the cystic duct and artery than it was with the open technique.

Another problem was the gallbladder tended to twist on the cystic structures after it was freed from its attachments to the liver, resulting in greater difficulty in clipping and dividing the cystic artery and duct.

In the course of these laparoscopic attempts to mimic the open method, it was realized that the same fidelity of identification obtained by taking the gallbladder off the cystic plate completely could be achieved by clearing only the lower part of the gallbladder off the plate, leaving the upper part of the gallbladder attached.

In addition, the twisting problem, which occurred when the gallbladder was detached completely, was not present when the fundus of the gall bladder remained attached to the liver.

At that point, the question became what was the least amount of gallbladder that must be separated from the cystic plate to achieve the fidelity of identification attained when the whole gallbladder is removed.

Logically, the amount is that which allows the surgeon to conclude that the gallbladder is being dissected off the cystic plate itself and not just being separated from attachments within the triangle of Calot.

The cystic plate, being made of fibrous tissue, usually has a dull white appearance.Occasionally, it is thin and translucent, allowing the underlying liver to be seen through it.

In cases with mild inflammation and areolar dissection planes, only a centimeter or so of the cystic plate needs to be cleaned free of gallbladder attachments to ensure that dissection is actually on the fibrous plate.

When there is greater inflammation that distance can be greater because fibrotic chronically inflamed tissues within the triangle of Calot can also have the same dull white color as the cystic plate.

The extent of dissection has to be that which results in the method being an adequate surrogate to dissecting the gallbladder off the liver bed entirely. Therefore, distance dissected needs to be that which makes it obvious that the only step left in the dissection—if the cystic structures were to be divided— would be removal of the remaining attachments of the gallbladder to the liver.

The making of 2 “windows” alone does not satisfy the requirements of CVS. To do so, enough of the gallbladder should be taken off the cystic plate so that it is obvious that the only step left after division of the cystic structures will be removal of the rest of the gallbladder off the cystic plate.

Also, although the common duct does not have to be seen, all fat and fibrous tissue must be removed from the triangle of Calot so that there is a 360-degree view around the cystic duct and artery, ie, the CVS should be apparent from both the anterior and posterior (reverse Calot) viewpoints.

Use of the CVS technique:

Standard procedure—mild and moderate inflammation present

The initial steps in performance of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy are similar in most methods.

A pneumoperitoneum is created, ports are inserted under direct vision, and graspers are placed on the gallbladder for retraction. The next step is to clear the triangle of Calot of fat and fibrous tissue.

This can be done with a variety of techniques, which include teasing tissue away with graspers or gauze dissectors, elevating and dividing tissue with hook cautery, and spreading tissue with blunt or curved dissecting instruments.

The dissection is commonly performed from the front and the back of the triangle of Calot.

Two points of safety for cautery are that it should be used on low power settings, typically 30 W and that any tissue to be cauterized should be elevated off surrounding tissue so that there is no unintentional arcing injury to surrounding structures.

Cautery should be applied in short bursts of 2 to 3 seconds or less to minimize thermal spread to surrounding structures.

Also, it is important that only small pieces of tissue be divided at one time because important biliary structures can be quite small in diameter.

Once this is done, there will be 2 and only 2 structures attached to the gallbladder and they can be visualized circumferentially.

At this point, the CVS has been achieved and the cystic structures can be divided.

If any doubt exists, as can occur when inflammation is severe, then more of the gallbladder should be taken off the cystic plate, including right up to the fundus, if necessary.

The CVS is not a dissection technique, but rather a technique of identification.

Affirmation of the CVS should take place at a pause in the operation and should be treated like a second timeout. The critical view should be demonstrated and ideally the surgeon and physician assistant, if present, should agree that it is achieved.

CVS in severe inflammation :

Surgeons are more likely to dissect the common bile duct circumferentially and believe it is the cystic duct in the presence of severe acute and chronic inflammation.

This occurs because certain factors present under these circum- stances tend to hide the cystic duct and fuse the common hepatic duct to the side of the gallbladder.

It is clear from operative notes that such circumstances can result in a compelling deception that the common duct is the cystic duct. The result in many cases has been bile duct injury.

If the surgeon is using a method, such as the infundibular view technique, and has come around the common bile duct thinking that it is the cystic duct, a 360-degree view of a funnel-shaped structure resembling the union of cystic duct and gallbladder can be obtained.

As this funnel shape is the requirement for identification by this method (infundibulum = funnel), the common bile duct will often be clipped and divided.

The common bile duct can be similarly dissected in error when using the critical view technique, but it will not be divided at this point because the other conditions for the CVS have not been met. The cystic artery has not been identified, the triangle of Calot has not been completely cleared, and the base of the cystic plate has not been displayed.

Under the same inflammatory conditions that lead to biliary injury in the infundibular view technique, the surgeon using the CVS will have difficulty proceeding after isolation of the common bile duct. This is actually desirable and should suggest that there is a problem.

It is important that the surgeon recognizes when this step in the operation becomes very difficult because it suggests there is a problem and additional attempts to attain CVS laparoscopically should be halted. Options include intraoperative cholangiography, conversion to open cholecystectomy, or soliciting the help of a colleague.

Stated otherwise, the critical view method is superior to the infundibular technique under conditions of severe inflammation because it is more rigorous.

The patient is protected precisely because the surgeon cannot usually achieve a misleading view. However, although CVS will usually protect against making incorrect identification, it will not protect against direct injury to structures by persistent dissection in the face of highly adverse local conditions.

Evidences that CVS prevents biliary injuries :

1) Yegiyants and colleagues reported on 3,042 patients who had laparoscopic cholecystectomy using CVS for identification in the period 2002-2006.The study was limited because data were obtained from an administrative database and CVS was not used in all laparoscopic cholecystectomies.

One bile duct injury occurred in an 80-year-old patient with severe inflammation. The injury occurred during dissection before the CVS was achieved, ie, none of 3,042 patients having laparoscopic cholecystectomy had an injury because of misidentification.

The expected rate of injury was between 2 and 4 per 1,000 cholecystectomies and most would be expected to result from misidentification. The actual rate of injury was much lower than the expected rate.

2) Avgerinos5 and colleagues reported on 1,046 patients having laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a single institution from 2002-2007.5 In 998 cases CVS was used. The conversion rate was 2.7%. There were 5 bile leaks, which resolved spontaneously. No major bile duct injuries occurred.

3) Heistermann6 and colleagues reported on 100 patients who had laparoscopic cholecystectomy using CVS.

The purpose of the study was to determine how often it was possible to attain CVS and demonstrate it with photo documentation. Despite a high incidence of acute cholecystitis and prior abdominal surgery, 97 of 100 cholecystectomies were completed laparoscopically after achieving photo documentation of CVS. There was 1 postoperative cystic duct stump leak.

4) Wauben7 and colleagues reported on use of ductal identification techniques in The Netherlands, including CVS.In this survey, it was found that Dutch surgeons used a variety of techniques for ductal identification, but few surgeons used CVS.

Subsequently, the Dutch Society of Surgery established a commission to study the problem of biliary injury in that country. The commission developed best practice guidelines for performing cholecystectomy and adopted CVS as the standard method of performing ductal identification.

Photo documentation of CVS before division of the cystic duct was recommended in these guidelines.

In summary, there is no Level I evidence that CVS reduces bile duct injury. To prove this claim would require a randomized trial.

The difficulty in performing such a trial can be illustrated as follows: even if there was a 4-fold increase in the incidence of biliary injury from 0.1% to 0.4% as a result of introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, it would be difficult to detect because a randomized trial would require 4,500 patients per arm to detect that difference at a 95% confidence level.

The logistics and cost of performing a surgical trial of this magnitude are overwhelming.

Probably the best that can be achieved is the all or none Level I type of evidence, in which it is shown that biliary injuries resulting from misidentification do not occur when a particular technique is used; from a practical perspective, that would be sufficient.

The case series of Yegiyants and colleagues8and Avgerinos and colleaguesapproach that standard. The results of the Dutch best practices initiative will be of great interest and might provide additional support for CVS if the policy is implemented successfully and if it results in a reduction in biliary injuries in The Netherlands.

PROFORMA

6. Study Proforma :

Clinical Details:

Symptoms :

- Pain :

- No of attacks : colic-

- Acute cholecystitis in the past :

- Any Medication intake

- H/o Jaundice :

- H/o cholangitis:

- H/o pancreatitis :

- Associated diseases :

- Past surgical history :

- General examination :

- Weight :

- Abdomen :

- Other systems :

Preoperative Investigations:

- Hb TC DC ESR Urine examination

- RBS Urea Sr. Creatinine Sr. Cholesterol

- LFT BT CT

- PT, aPTT

- USG Abdomen: Gall bladder: No of stones

- Wall thickening

- Contracted or Normal

- Any other abnormality

- Associated findings: CBD

- Pancreas

- Liver

- Others

- ECG Chest X Ray

- Any other relevant investigations:

- Pre-operative pain score (VAS)

Surgery Details :

- Date of operation:

- Anaesthesia :- General anaesthesia

- Intra-operative findings

- Duration of surgery: minutes

- Pain score (VAS) in post op:

@24hrs:

@48hrs:

- Hospital stay (in days)

- Days off work

Problems Encountered During Surgery:

- Spillage - Bile, Stones

- Bleeding

- Cause of the problem encountered:

- Source:

- Management:

- Any change in plan: yes/ no

- Reason for Failure to demonstrate CVS

- Others:

- Drainage: Used or not

Extra analgesia required :- Dose: Days:

- Oral feeds when started

- Ambulation

- Hospital stay

- Bile leakage

- Haemorrhage

- Surgical emphysema

- Wound infection

- Pulmonary complications

- Others if any

Follow Up :

- Clinical Examination:

- Investigations on suspicion of complications:

7. RESULTS :

One hundred (100) patients underwent admission for cholecystitis.

The mean age of the study population was 36.50years, with therange of 10 to 60years in this study, the total number of male patients being 52(52%)while the number of female patients being 48(48%)with M:Fratio being 1.10 : 1.

Analysis ofage groups showed ahigh incidence ofacutecholecystitis among adults between 30-40years( 38%) . The highest prevalence of acute cholecystitisinmales was observed in the agegroup 31-40 years (47.5%)as also forfemales it was in in whom it was (33.33%).

The lowest prevalence ofacute cholecystitis inmales and female was inthose aged above 51 yrs (12%).

Table : Age And Sexwise Distribution Of Patients

Chief Complaints

In our study abdominal pain was the main symptom followed by fever and then nausea/vomiting.

General Physical examination

Per Abdomen Examination

Laboratory Findings

Ultrasound findings

Operative Technique :

Table 1: Comparison between the two different techniques of laparoscopic cholecystectomy

No mortalities occurred in the series. Morbidity was 0.1% (1 patient) in group 1 and 0.2% in group 2 (2 patients).

One biliary leak from the cystic duct in the first patient (acute gangrenous cholecystitis) resolved after an endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed on postoperative day 1.

The other 2 patients had intraoperative hemorrhages, both controlled with bipolar coagulations and clip applications; 1 of the 2 patients required blood transfusions.

No difference was found regarding pain, wound infections, time to first passage of stool, re-feeding, or discharge.

Neither group required the use of high-tech instruments (Harmonic or radiofrequency devices) apart from mono- or bipolar cautery.

Cholangiography has never been performed intraoperatively.

Significant differences were found in the operative times. Both median times (51.5 min vs 69.7 min) and average time divided by case-difficulty (defined by different grades of gallbladder inflammation) were in favor of the CVS approach. The difference was minor (but still significant) for acute cholecystitis (Table 2).

Table 2 : Comparison between the operative times in both groups

Histopathology revealed acute cholecystitis in 37 cases and chronic cholecystitis in 22 cases. For the rest of patients histopathology was suggestive of acute onchronic cholecystitis.

8. DISCUSSION:

Figure 1: The “critical view of safety.” as shown by Strasberg9 The triangle of Calot is dissected free of all tissue except for cystic duct and artery, and the base of the liver bed is exposed. When this view is achieved, the two structures entering the gallbladder can only be the cystic duct and artery. It is not necessary to see the common bile duct.

Prevention of iatrogenic bile injuries is still a matter of significant concern, despite almost 25 years passing since the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed.

The debate has sparked renewed interest since the introduction of natural orifice surgery (NOTES)10and single port access surgery11.

In Italy, a national survey shows an incidence of 0.42% of major bile injuries during LC in 56 591 patients, with higher rates in cholecystitis and low-volume practice subgroups.12

The approach to the gallbladder’s pedicle is of utmost importance for the prevention of injuries. Three main techniques have been standardized.

The oldest and most common approach is the infundibular one. The classic dissection of Calot’s triangle might misrepresent vascular or biliary anatomical variants, which are frequently located in the medial part of the area. 13

Strasberg identified an “error trap” 14to avoid, regarding the IN technique, in which the common hepatic duct might be mistaken for the gallbladder wall in severe inflammation.

Katkhouda et al15 suggest the extension of the cystic duct’s dissection to the confluence with the common hepatic duct, to perform what he calls a “visual cholangiography.”

Another way to prevent injuries, more frequently performed in open surgery (but also described in LC, mostly with the use of ultrasonic sharp dissection16), is the “dome-down” or “fundus-first” technique, often advocated for acute cholecystitis.16

The error trap of this technique (following Strasberg) concerns the possible injury to the right hepatic artery, which might be retracted downwards, along with the gallbladder.17

Routine intraoperativecholangiography has been advocated by many authors:18 its use, especially in emergencies, calls for some organization in the operating theater and operative expertise. Alas, intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) does not seem to prevent bile duct injuries, even if it helps with immediate identification of the injury.19

IOC ineffectiveness at lowering the rate of biliary lesions has been confirmed in large multicenter trials. There was no need, in either of our groups, for intraoperative cholangiograms, which are not routinely performed in our patients.

The importance of cholangiography in clarifying unclear anatomy is ascertained, but largely unnecessary in our opinion, both for the rate of failure of cystic duct cannulation and for the possible injuries that may be caused by the incautious forcing of the biliary catheter through the cystic valve, especially in inflammatory entanglement of the duct.

The effort to standardize an approach to the cystic artery and duct that could effectively avoid the area where ductal and arterial anomalies are likely to be encountered brought Strasberg et al to outline the “critical view of safety.” Since 1995, their suggestion has been little mentioned, until the initial papers and retrospective series started analyzing the results of the technique.20,

After these studies, other authors21from around the world have started collecting cases and standardizing the operative technique. The results seem promising, as in large single- institution series, the “observed BDI rate drops from 1/9 to 1/15, representing an order-of-magnitude of improvement in the safety of LC”: the authors consider these results as superior to routine cholangiography.22

Other authorshave tested the validity of the technique even in acute cholecystitis (performed by entering the inner subserosal layer for dissection). The approach is considered viable even for NOTES gallbladder surgery. 23

A safe cholecystectomy technique is particularly important when considering trainees or young surgeons, who have scarce experience in biliary anatomical variance and are at risk of causing a major injury under emergency conditions (intraoperative bleedings, difficult anatomy, severe inflammation).24

9. CONCLUSIONS :

Our results show no difference in terms of complications between an experienced laparoscopic surgeon using the In fundibular approach or the CVS; a minor number of intraoperative bleedings, without statistical significance, could validate the rationale of the CVS approach towards dissection of an area without vascular abnormalities; moreover, the distal clipping of the cystic artery may favor easier dissection and consequently fewer accidental bleedings, especially in inflammatory conditions.

The power of our study is not sufficient to analyze the outcome of the “bile duct injury rate,” as multicenter trials are required because of the low expected rate of events.

The shorter operative times are symptomatic of increased confidence due to the technique, which probably makes the surgeon feel more secure, both with inflamed and uninflamed anatomy.

We believe that a diffusion of this simple, practical technique might be desirable in training hospitals, residencies, and district hospitals, or anywhere laparoscopic experience might be basic or limited to standard operations.25

The results of CVS in the literature and in the present study forecast the approach as the future gold standard in the dissection of the gallbladder elements, and a further dissemination of the technique is important, especially for training purposes.

10. BIBLIOGRAPHY :

1. A prospective analysis of 1518 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. The Southern Surgeons Club. N Engl J Med 1991;324: 1073–1078.

2. StrasbergSM,HertlM,SoperNJ.Ananalysisofthe problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am CollSurg 1995;180:101–125.

3. Davidoff AM, Pappas TN, Murray EA, et al. Mechanisms of major biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 1992;215:196–202.

4. Strasberg SM, Sanabria JR, Clavien PA. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Can J Surg 1992;35:275–280.

5. AvgerinosC,KelgiorgiD,TouloumisZ,etal.Onethousand laparoscopic cholecystectomies in a single surgical unit using the “critical view of safety” technique. J GastrointestSurg 2009;13:498–

503.

6. HeistermannHP,TobuschA,PalmesD. [Preventionofbileduct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. “The critical view of safety”]. Zentralblatt fur Chirurgie 2006;131:460–465.

7.Wauben LS, Goossens RH, van Eijk DJ, et al. Evaluation of protocol uniformity concerning laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the Netherlands. World J Surg 2008;32:613–620.1. Cuschieri A, Terblanche J. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: evolution, not revolution. Surg Endosc. 1990;4:125-126.

8.YegiyantsS,CollinsJC,YegiyantsS,CollinsJC.Operative strategy can reduce the incidence of major bile duct injury in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am Surg 2008;74:985-957.

9.Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. Isolation of right main and right sectional portal pedicles for liver resection with- out hepatotomy or inflow occlusion. J Am CollSurg 2008;206: 390–396.

10. AuyangED,HungnessES,VaziriK,etal.Naturalorifice translumenal endoscopic surgery (NOTES): dissection for the critical view of safety during transcolonic cholecystectomy. SurgEndosc

2009;23:1117–1118.

11.Hodgett SE, Matthews BD, Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. Single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC): initial experience with critical view dissection and routine intraoperative cholangiography. SurgEndosc 2009;23:S332

12. Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Giovannini I, Ardito F, D’Acapito F, Vellone M, Murazio M, Capelli G. Bile duct injury during lapa- roscopic cholecystectomy. Results of an Italian national survey on 56591 cholecystectomies. Arch Surg. 2005;140:986-992.

13. Strasberg SM, Eagon CJ, Drebin JA. The “hidden cystic duct&rd